River spans in Yardley and Middletown reflect engineering genius of 100 years ago.

Whether you go by kayak down the mighty Delaware or by canoe on Neshaminy Creek, it’s astounding to slide beneath towering archways built to carry passenger and freight trains through Middletown, Langhorne and Yardley more than 100 years ago. The bridges were made to last forever. It seems to be working. Today they’re just as serviceable for oh-so-long Norfolk Southern and CSX freight trains plus SEPTA passenger trains as they were in the early 20th century.

In the river off Yardley, the contrast between a new interstate highway span and a century-old railroad trestle can be seen in a glance. Near the borough’s upstream border in Lower Makefield, the replacement I-295 Scudders Falls bridge is progressing 20 feet above the roiling Delaware.

Downstream about two miles is the 14-archway Yardley Bridge standing 70 feet above the river flow. That’s more than three times as high. It’s perhaps a no-brainer that to cross rivers, gorges and narrow valleys, railroads had to keep everything on the level. At least no more than a slight gradient. Locomotives muscling mile-long trains could not make steep climbs. So that meant stupendously high trestles and mountains of fill to keep tracks more-or-less on the level as they traversed hilly Pennsylvania and beyond.

Prior to 1900, trestles like the Neshaminy Creek Viaduct in county-owned Playwicki Park in Middletown and similar bridges over Route 413 in Langhorne were constructed of stone and brick masonry. In Yardley, the trestle bridging the Delaware pioneered the use of cost-saving poured concrete.

On a solo kayak mission from Yardley to Morrisville, I set out to inspect the trend-setting dual railroad trestle used today by CSX freight trains and SEPTA’s West Trenton commuter line to Philadephia. For me, this was a unique adventure, mindful of my ancestral grandfather Henry Grow of Ardmore. He was an architect of covered railroad bridges in Southeastern Pennsylvania and New Jersey in the mid-1800s. He eventually moved to Utah where he designed and built the territory’s first two suspension bridges over the Weber and Jordan rivers. He also designed the iconic Mormon Tabernacle in Salt Lake City. There he used wooden truss techniques he learned in Philadelphia to create the largest hall in the world with a domed roof unsupported by columns and capable today of seating 13,000 people. A similar scaffolding methodology went into the Yardley bridge.

So here I was afloat on the deceptively swift Delaware, nuzzling up to the trestle’s center pier to view what from the distance seemed a relic of Roman antiquity transplanted to our shore. Paralleling the bridge 30 feet away are vine-strangled masonry piers built in 1874. They once supported the former Yardleyville Centennial Bridge. That wrought-iron truss span carried New York City visitors to the nation’s Centennial observance in Philadelphia in 1876.

The replacement bridge three decades later was an experiment in new technology – reinforced concrete of the type invented by Doylestown’s Henry Chapman Mercer. He pioneered the technique for his Fonthill Castle home and Mercer Museum in the borough. The Reading employed the same method – placing twisted iron rods called rebars within poured concrete to provide strength and durability. The Yardley Bridge is 1,445 feet long – more than a quarter mile. Given the length of the trestle, weathering conditions, weight of freight trains and threat of cement cracking, the railroad used far more felt expansion joints than deemed necessary. It was a conservative move to enable concrete sections to expand and contract under all weather conditions without breaking.

For these reasons, the construction was revolutionary. “Engineering News” in 1913 touted it as “one of the largest two-track concrete railway bridges in existence.”

The way it was built is interesting.

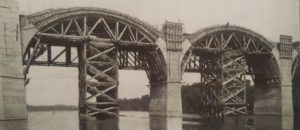

Work began in the spring of 1911with creation of 13 concrete bridge support piers positioned at regular intervals across the river. The largest at 20 feet wide centered the bridge on the Pennys-Jersey state line. Using coffer dams to temporarily seal off each abutment from the river flow, workers anchored the piers to bedrock on the river bottom.

Next, workers fashioned a web-work of wooden support towers like frontier forts sitting in the river between the piers to uphold molds for poured concrete to create the archways. Crews from Yardley on the Pennsylvania shore and West Trenton on the New Jersey shore moved out from the state line pier toward their respective landings. A narrow gauge railroad and later a cable way of mobile buckets conveyed wet concrete from mixing plants to where it was needed.

The Yardley Bridge debuted in the summer of 1913 as an engineering marvel. Examining the structure a century later, I threaded my kayak in and out of the archways, taking photos amid the swirling current as a SEPTA commuter train scooted past high above. The bridge, seen from river level, is majestic, a favored subject of artists and photographers through the decades. Today, it easily fits on my list of 22 Wonders of Bucks County.

Sources include “The Yardley Bridge across the Delaware River, Philadelphia & Reading RR” published by Engineering News on May 29, 1913. It’s available at the Lawrenceville branch of Mercer County Library.