Iron mill in Upper Bucks County played key role in winning the American Revolution.

There’s an inescapable irony in visiting the historic Durham iron furnace built in 1727. It sits just off Route 212 in the tiny village of Durham in Upper Bucks.

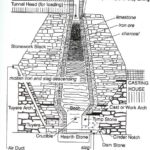

Before the American Revolution, the foundry smelted iron ore from two local hills to produce bar iron. Locally-made Durham river boats shipped the iron down the Delaware River to Trenton, Bristol and Philadelphia where it was converted into pots, pans and iron stoves. Ardent English Crown supporter Joseph Galloway of Bensalem formed the Durham Furnace Company with a Philadelphia-based partnership. Galloway and wife Grace later became sole owners, unwittingly leasing it to George Taylor. That’s the rub.

Taylor used the furnace to produce lots of ammunition including cannon balls for George Washington and his Continental Army. He also signed the Declaration of Independence and organized area militia units to fight the Brits. You might say Durham’s munitions and river boats enabled Washington to make his famous crossing of the Delaware and win the Battle of Trenton at Christmas 1776. As for Galloway, he fled to England to avoid prosecution for helping the Redcoats occupy Philadelphia during the war. The new government seized Galloway’s property including the furnace over which a granary was built in years following.

So, hey, the preserved Durham Mill and Furnace is of major historic significance in Bucks. As such, we eagerly accepted an invite last week from Stephen Willey to tour the site. Grand kids Dashiell, 8, and Margaux, 4, mom Genevieve and I wheeled up Route 212 to the mill to meet Willey and members of the local historical society including David Oleksa, its president.

This was a rare opportunity since the building normally is closed to the public except on Durham Day in October.

Durham village is post-card cute and hugs swift Cooks Creek. Two mountains of iron ore – Rattlesnake Hill to the east and Mine Hill to the southwest – descend steeply to the town and the furnace ruins, over which a 3-story grist mill was built in 1820. The mill sits next to a pocket park where a Durham boat sits beneath a canopy with public access.

The Durham Historical Society is well-versed in mill operations – from how candles were used to illuminate operations (and were a fire danger) to cantilevered chutes and cuppers that bore threshed wheat and other grains to the top floor and then down to stone grind wheels from France that reduced grain to powdered flour. Rooms in the mill are vast with sliding metal doors to seal them off in case of fire. Massive, interlocking iron gears survive from two centuries ago. Well-worn hardwood floors are a testament to an industrialized building where rail cars once sidled up with wheat to grind into baking flour.

To Dashiell, our daring climb a third-floor ladder to the cupola with Willey and then staring down from cat walks into the dark recesses of six empty grain silos was thrilling. Mom Genevieve was impressed by all the gears, leather conveyor belts and chutes that dominate any view of the mill on any level. “To think all that was powered without electricity, just with water is amazing. They were smart people back then,” she said.

To Dashiell, our daring climb a third-floor ladder to the cupola with Willey and then staring down from cat walks into the dark recesses of six empty grain silos was thrilling. Mom Genevieve was impressed by all the gears, leather conveyor belts and chutes that dominate any view of the mill on any level. “To think all that was powered without electricity, just with water is amazing. They were smart people back then,” she said.

In fact 200 years ago, immigrants from Germany dug out a mill run and pond to channel water from Cook’s Creek into the building where it flowed over a gigantic water wheel in the basement next to the blast furnace ruins. The wheel’s motion powered all the machinery in the granary overhead until 1967.

Dim illumination in parts of the mill caused Margaux to warily eye the rafters after someone pointed to “bat droppings” on the floor. A petrified raven perched on a beam on the first floor also was spooky, given the legend the bird appears at a new location every time the mill keeper enters the building. Inquisitive Dash was opening one of the granary chutes when a bit of ancient wheat dusted down on him. Inside he found remains of a sparrow.

Folks in Durham hope one day to grind locally grown wheat into flour at the mill in the old fashioned way. “We have a rough estimate of $80,000 to restore the mill to working order with a water-fed wheel turning the grinding wheels,” said Willey after our visit. “We even discussed the possibility of using the water-powered wheel to generate electricity. The beauty of that would be to combine 1820 German state-of-the-art technology with a 2020 German (Rexroth Bosch, among others) state-of-the-art hydro-power system.”

The society is finalizing its plan in coordination with township government. Members are encouraged by news a Kentuckian millwright has restored Stover Mill in Tinicum and Washington Crossing Historic Park’s grist mill in Solebury and is eager to do the same in Durham. Here’s hoping for success.

Among sources for this column include “Place Names in Bucks County Pennsylvania” by George MacReynolds and Durham’s history website, www.durhamhistoricalsociety.org. Tax deductible donations are welcomed at the nonprofit Durham Historical Society, PO Box 52, Durham, PA 18039-0052.

An interesting discussion is definitely worth comment.

I do believe that you should publish more on this issue, it may

not be a taboo matter but typically folks don’t discuss such topics.

To the next! Cheers!!