The Lambertville-New Hope bridge posed quite an obstacle for the 7-year-old in a Conestoga wagon.

I’ve had many adventures on the Delaware River. Aboard a sailboat, in a kayak, riding shotgun in an amphibious Sunbeam convertible, on an inner tube, even swimming across with my dog Lucky. But I’ve never crossed in a horse-drawn wagon. That’s the reaction I had to an email from Frank Keith in Mount Laurel, N.J. after he read my column about Conestoga wagons published on Aug. 31.

“I assume you’ve read Rinker Buck’s book about retracing the Oregon Trail in a Conestoga wagon and his experience getting the wagon across the Delaware in an earlier trip,” noted Frank. “That may merit a followup article by you.”

I was intrigued. Crossing deep water in a covered wagon required cutting down trees to make a raft called a “scow”. You’d tie your wagon to the beams and set sail. The wagons were waterproofed, enabling them to float if necessary. Is that how Rinker crossed the river? I checked his book.

Turns out he wrote of a boyhood journey in 1958 on a Conestoga from the family’s horse farm in Somerset County, N.J. to Gettysburg. His father, a World War II pilot, wanted his kids to experience history the old fashioned way. That “dream summer”, as Rinker put it, had its challenges, particularly on reaching Lambertville to cross the river – not by water but by the bridge to New Hope. Its metal grating was made for cars, not horses. The animals could see the river through the grates as they approached. They reared, dangerously threatening the wagon with kids aboard. Rinker’s dad motioned cars behind to back up, calmed the horses and inched them and the wagon back down off the span.

Determined to go forward, he devised a plan.

Since there was a wooden pedestrian walkway to one side of the vehicle lane, he instructed Rinker and his older brother to lead the horses across on the boardwalk. “Boys,” he said, “when you get up on the walkway, if the horses start to fuss or run away, just let them go. When a horse is afraid it just wants to be free to take care of themselves. So just let them go if they rear and balk.”

Rinker was wide-eyed. “Dad. That’s crazy. They’ll run away and we’ll never catch them.”

“Let them go,” his father assured. “A horse will never go far. Once they’re past what they’re afraid of, they stop. Get the team onto the planks and then let them go if you have to. We’ll catch them on the other side.”

Rinker said he felt “queasy” and “frightened by the way the bridge shook and rattled underfoot every time a car passed.” He believed his father was out of his mind. But he wasn’t. “Up near the bridge, while my brother led Benny to the walkway, I stood back with the buggy whip hidden behind my back, holding the other horse, Betty, with a line. When Benny balked at the metal grating, I surprised him from behind with a good crack on the ass and he vaulted to the wooden planking, galloping a few strides before he calmed down. My brother ran several strides ahead of him and had no trouble leading him across.

“It was an eerie, incongruous feeling, being suspended 70 or 80 feet above the Delaware River, herding horses across a narrow wooden walkway that seemed to stretch forever to the distant bank.” The trailing horse stalled at the grating on the New Hope side. Rinker gave her a quick slap on the rump and she leaped over. He jumped with her. “It was all one fluid motion: leap, grab the line, flip over to a sitting position, and then get hauled on my ass by a big draft mare for the Nantucket sleigh ride into New Hope.”

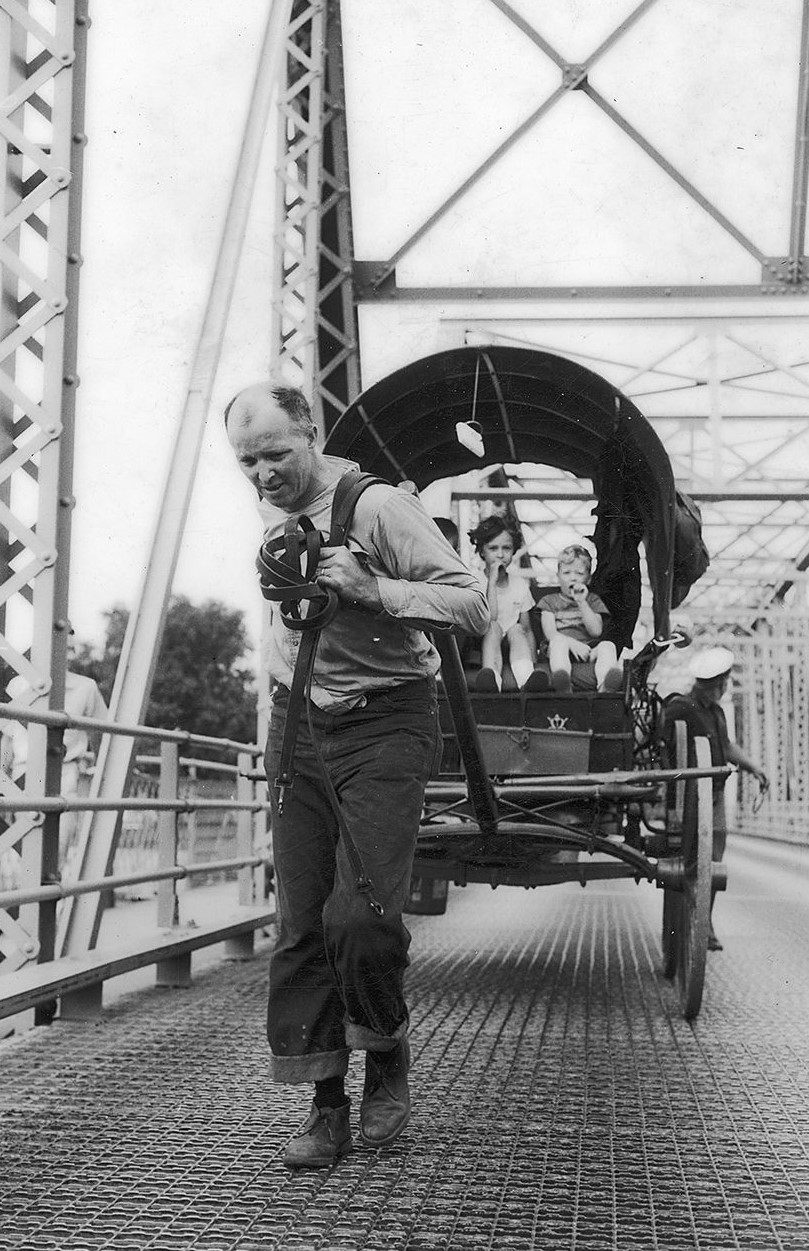

The horse saw a patch of grass and abruptly stopped to graze as predicted. As for Rinker’s dad, he was in harness to the wagon in Lambertville, pulling it across the bridge with brute strength as young kids aboard watched. It created quite a spectacle. In the end all was well.

The rest of the journey to Gettysburg was joyous. “Along the cool, shaded lanes of Bucks County, we sang songs together to pass the time, and took turns learning to drive the team,” Rinker reminisced. “On warm afternoons the bumping of the wheels over gravel roads and the rhythmic clopping of hooves made me sleepy, and I loved stretching out in the back of the wagon and napping on a bale of hay.”

The romance of that summer would carry over years later when Rinker and his brother completed an epic covered wagon journey of more than 1,000 miles on the historic Oregon Trail from Missouri to the Pacific Coast. The experience evolved into Rinker’s best selling book.

***

Sources include “The Oregon Trail: A New American Journey” by Rinker Buck published in 2015 by Simon & Schuster, and a tip of the hat to Frank Keith who read my earlier column in the Burlington County Times and to Rinker Buck for his help.