A Bucks man was the locomotive engineer on historic trip to the Chicago world’s fair.

A book of mine featured on the History Channel reveals how a revolutionary machine saved submarine sailors in 1939 from their wrecked vessel on the ocean floor off New England. “Man, Moment and Machine” arranged for survivors to revisit the rescue bell 50 years after their harrowing ordeal.

I thought of this when I came across the tale of George W. Scott and the iconic John Bull, the oldest functioning steam locomotive in world history. It doesn’t involve a dramatic rescue. But it does reunite man and historic machine.

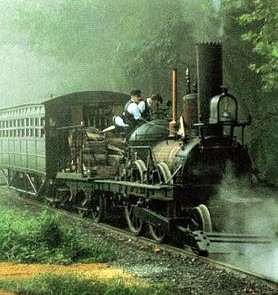

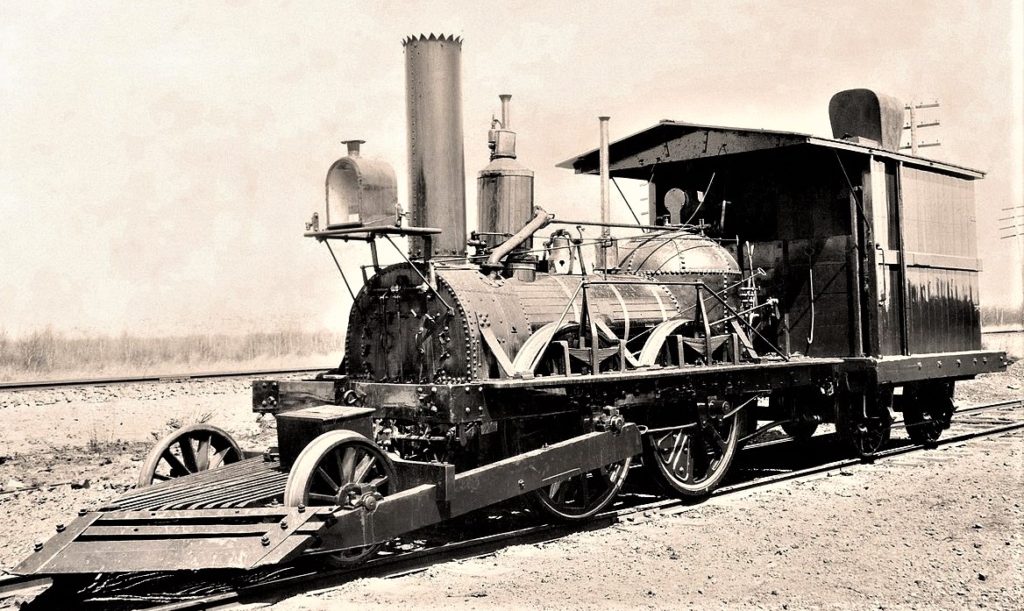

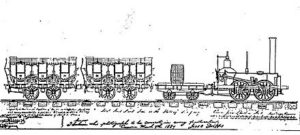

George Scott was born in 1822 in Bucks County. Where exactly is unknown. He was the oldest of 6 siblings. At age 9, he must have reveled at the arrival in Philadelphia of the region’s first steam locomotive on a sailing ship. It arrived in pieces and had to be assembled without instructions. Nicknamed “John Bull” after the cartoon caricature for England where it was built, it made its first run on Sept. 15, 1831 on a New Jersey railroad routed from Camden to Amboy through Burlington City and Bordentown. With a wheel ratio of 4-2-0, the steam engine was built for English iron rails that were far superior to those used in America. John Bull occasionally tipped over rounding curves. To cure that, a fan-tailed leading truck was attached to the nose to keep the locomotive on track through turns.

John Bull under full steam could make 15 mph. It reduced the 2-day travel time by horse from New York to Philly to a mere 5 hours. Its power, gloated the railroad, had “almost annihilated time and space.”

Young George Scott could only dream of taking John Bull’s throttle. For him, the death of his parents when he was 12 left him fending for himself as a farm laborer and caring for his five younger brothers and sisters. By age 21, he had become an apprentice carpenter plus legal caretaker for his siblings. Meanwhile, John Bull chugged along reliably on the C&A on the far side of the Delaware River linking Philly with New York City. When George turned 24, he joined the railroad to fulfill his dream of becoming a locomotive driver. He achieved his goal in 1852 and drove John Bull for years before its retirement from service and storage in Bordentown in 1866.

George remained an engineman after the Pennsylvania Railroad acquired the C&A in 1871. The new owners re-fired John Bull’s boiler so it could steam from Bordentown to Philadelphia to appear at the 1876 Centennial Exposition. Afterwards the Smithsonian Institution accepted the locomotive for permanent preservation in Washington. Seventeen years later, the museum temporarily released the antique back to its former owner so it could make one last full run from Jersey City, N.J. to Chicago for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition where advances in railroading would be celebrated.

The Pennsy tapped George Scott, 71, to drive 62-year-old John Bull. To Railroad Age Gazette, it was a perfect match. “In his career as a railroad man Scott touched practically every link in the chain of developments that make up the history of American railroads. In the year of his birth there was not a mile of commercial railway in the world, and hardly the first successful experiments with steam transportation on land had been made.”

With two vintage passenger coaches attached, John Bull pulled out of Jersey City on the morning of April 17 to begin the 5-day run to Chicago. A large crowd cheered wildly amid the shriek of the engine’s whistle and clouds of steam exhaust. The first 31 miles to New Brunswick drew an estimated 50,000 spectators as the train passed at 15 mph. Thousands greeted it in Trenton and Bristol where railroad executives hopped aboard.

The train reached Philadelphia at 5:42 p.m. where an enormous crowd “knew no bounds,” reported the New York Times. “They made frantic efforts to board the train but were kept back by a squad of policemen. Cheer after cheer went up and the demonstration lasted until the train, five minutes later, backed out of the station.”

In Chicago, the locomotive gave rides to fair attendees before returning to the Smithsonian on Dec. 13. George Scott returned home to Bordentown where he passed away in 1915 at age 93.

Sixty-six years later the locomotive marked its 150th birthday on Sept. 15, 1981 by steaming several miles on rails beside the Potomac River, making John Bull the oldest operable in world history. Four years later, the Smithsonian shipped it to Dallas, Texas for a brief exhibition – making it the oldest locomotive ever to travel by air.

Today the storied engine representing the dawn of U.S. rail travel remains on display at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington. An exact replica is closer to home at the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania in Strasburg.

***

Sources include “John Bull on the Way West” published in the New York Times on April18, 1893; “Landmark Object: John Bull Locomotive” by the National Museum of American History found on the web at https://americanhistory.si.edu/press/fact-sheets/landmark-object-john-bull-locomotive, and “The John Bull locomotive and its last engineman” published on May 7, 1915 in The Railway Age Gazette and in the Pennsylvania Railroad’s “Information for Employees and the Public” on Jan. 9, 1915.

Carl LaVO is author of “Back from the Deep” published by the Naval Institute Press. He can be reached at carllavo0