Reflections on the life of a Bucks County hero.

Memorial Day in my childhood meant rooting for Bill Vukovich to win the Indianapolis 500 during radio broadcasts on family outings in the High Sierras. Dad, our camper-in-chief, was one of the heroes of World War II. He endured most of the battles in the Pacific as a destroyer yeoman including a solo mission to successfully torpedo a Japanese battleship firing broadside at the onrushing USS Halford in Surigao Strait. Dad seldom discussed what happened nor did the subject come up on Memorial Days. On leave in mid-war to await battle repairs to his ship, Dad married Mom, fearing he wouldn’t return alive. I was his goodbye baby. As I would learn from Grandpa Carl, Dad was shaken to his core about going back to the front. It was Grandpa who counseled him, giving him the courage to fulfill his horrific duty. He did so, returning home at war’s end proud and unscathed.

Memorial Day today has more poignancy for me. A time to remember Dad. Most view Memorial Day as a holiday. I guess so if it means being off from work and enjoying a Jersey Shore beach fling. But it’s really intended to be a solemn remembrance, a tradition dating to the Civil War era when just about every family suffered losses, North and South. This Memorial Day I recall one of them. Capt. Henry Clay Beatty.

Born in Bristol, the son of a bank cashier, young Beatty yearned to be a lawyer. Philadelphia attorney Charles Gibbons and Anthony Swain of the Bucks County Bar tutored him between 1854 and 1857, enabling him to graduate from Penn law school. “He loved the truth, and no one ever found him a hair’s breadth out of its latitude or longitude under any circumstances,” recalled Gibbons.

When rebel forces attacked Fort Sumter in 1861, state government called up 15 army regiments. Beatty and his brother volunteered for duty in Company I from Bristol, known as the Montgomery Guards. The 100-man unit was among 10 mustered in Philadelphia as the 3rd Reserve Infantry Regiment. Three companies were from Bucks – the Applebachsville Guards from Upper Bucks, the Union Rifles from Central Bucks and Beatty’s company which elected him its captain.

The 1,000-man regiment deployed in mid-July to northern Virginia and then to the peninsula below Washington to reinforce the Army of the Potomac in anticipation of battle against Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. The two sides met on June 26 at what came to be called the Seven Days Battles. Though wasted by serious illness, Beatty led his company in a number of skirmishes.

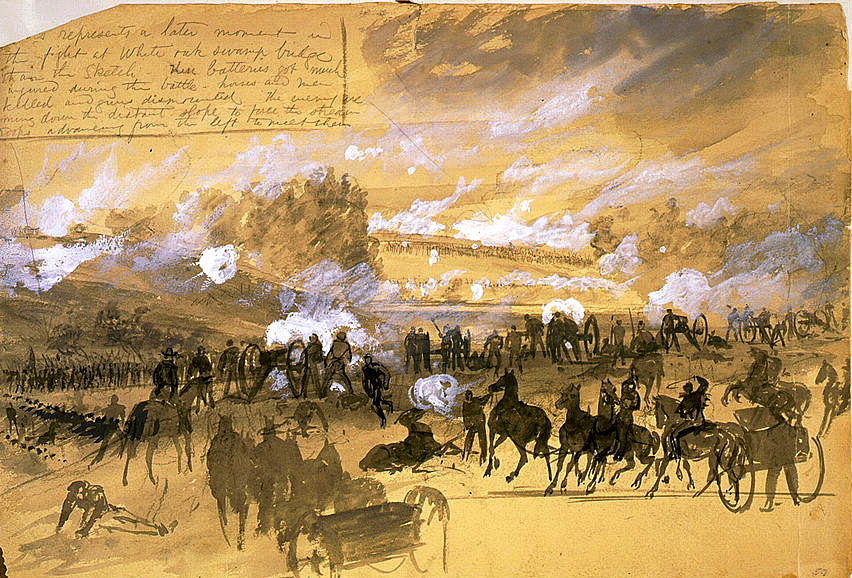

On June 30, 1862 the regiment fought valiantly at the pivotal Battle of White Oak Swamp during which a rifle ball lodged in Beatty’s leg. Despite his wound, the captain remained at his post in the midst of a withering artillery assault by enemy Major Gen. Stonewall Jackson. The Union army fell back. The next day Beatty had the lead removed at Fort Monroe on the James River and rejoined his company. The regimental commander, noticing how sick and injured he was, ordered him home to recover. Before his furlough was up however, he rejoined his company.

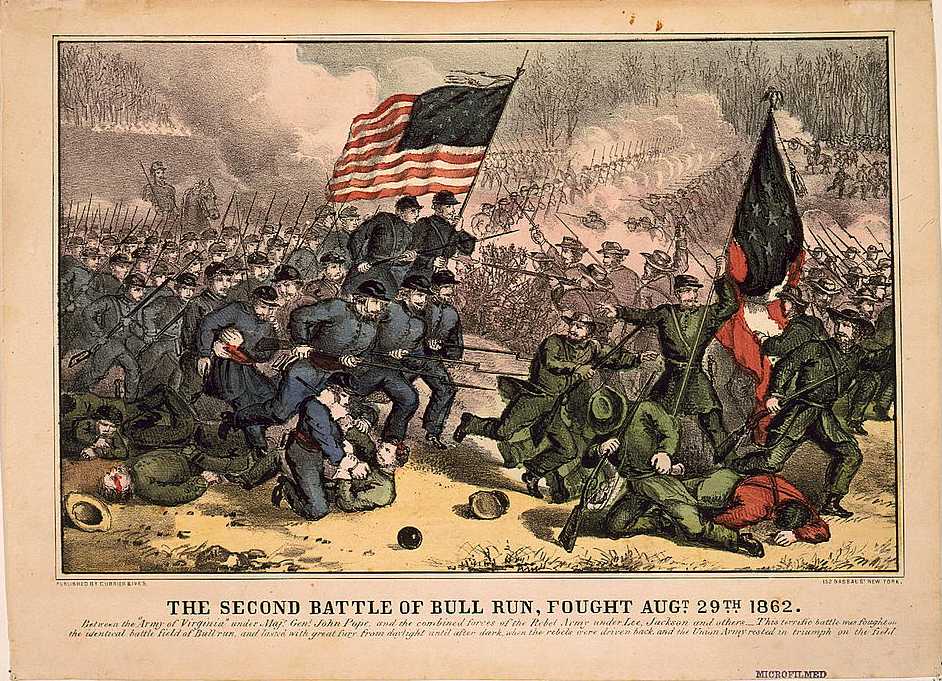

Then came the Second Battle of Bull Run at Manassas, Va.

On Aug. 30, 1862, two armies – Major Gen. John Pope’s Army of Virginia (to which Beatty’s company was attached) and Lee’s army – faced off. Pope believed he had trapped Lee’s men. However, Lee counterattacked with massed artillery and a frontal assault by 25,000, the largest simultaneous infantry charge of the war. During the chaotic battle, a large caliber rifle bullet fired in Beatty’s direction hit the ground, rebounded, struck a fellow soldier in the head, killing him, then hit Capt. Beatty, breaking his arm in two places and ravaging his hand. When his brother rushed to his side, Beatty ordered him back to his post. The captain fought on as the regiment retreated. Charles Carlin of Bristol, also wounded, helped the captain off the battlefield.

Beatty refused medical treatment until the next day. In order to save his life, surgeons amputated his arm and ordered him evacuated to Washington. On a steamboat sailing up the Potomac, he said he felt better. Moments later he faded and died.

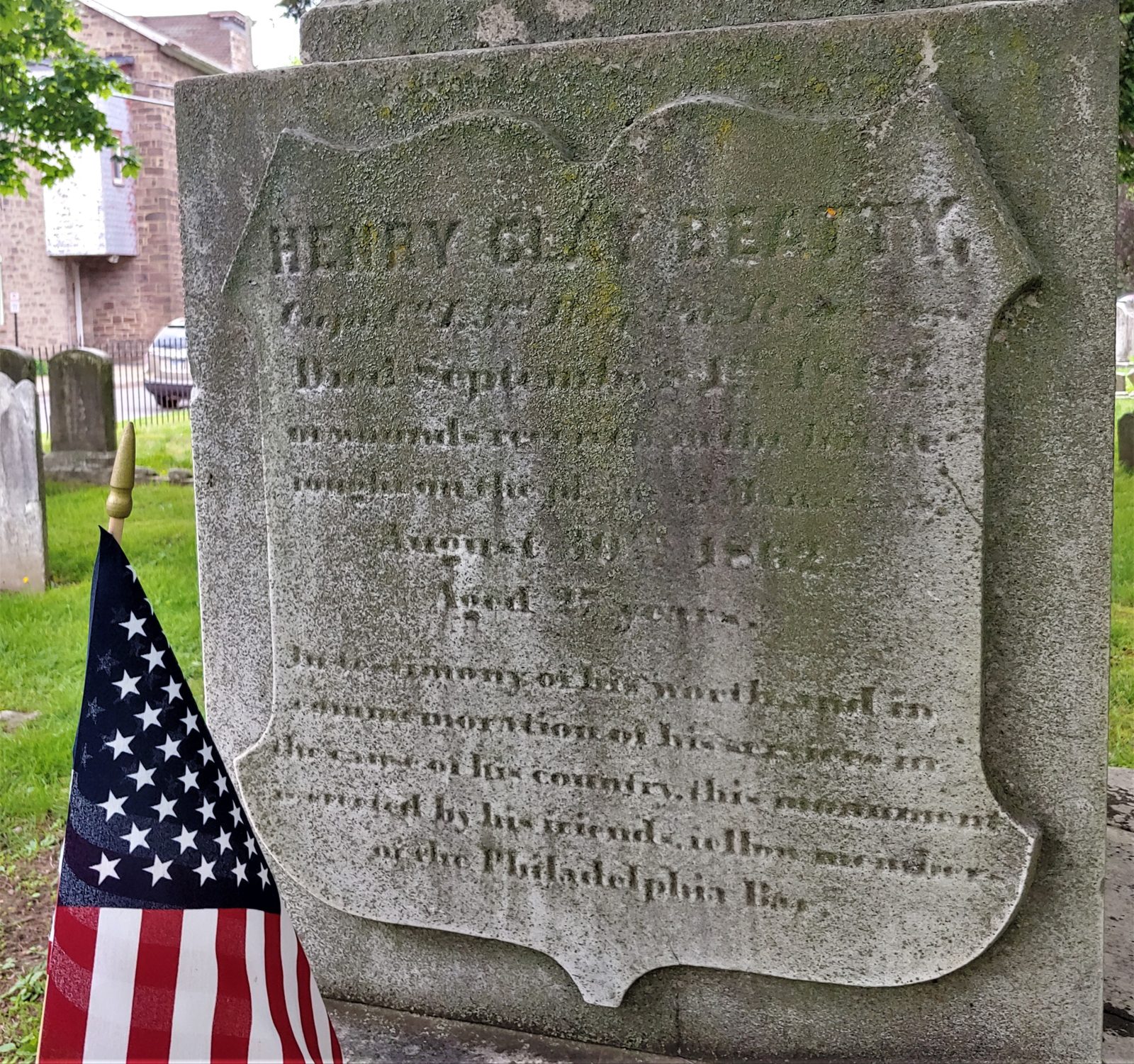

An honor guard returned Capt. Beatty’s remains to Bristol for ceremonial burial in St. James Cemetery beneath a monumental headstone. Local historian Doron Green said of the captain, “He considered duty to country as paramount to his own sufferings, and by that patriotic action gave to Bristol a hero, whose memory can never die.”

A reader eulogized him in the Bucks County Intelligencer:

“Harry Beatty.

“Captain of Company I, Third Pennsylvania Reserves.

“Fallen in battle! My brave friend,

“Warm tears from faithful eyes

“Bedew that grave where lulled to sleep

“Thy wounded body lies.”

Sources include “A History of Bristol Borough” by Doron Green published in 1911, and The Bucks County Civil War Museum, 32 North Broad St., Doylestown and found on the Web at civilwarmuseumdoylestown.org. The museum is open to the public every Sunday from 10:30 a.m. – 2 p.m.