The day an aeronaut fell from the sky and shook up Applebachsville.

I once contemplated flying in the Great American Balloon Race to the Jersey Shore. Two dozen hot air balloons were to lift off from Eakins Oval in front of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Though I deferred, my daring newspaper colleague Wynne Wert, former United Airlines flight attendant from Middletown and fellow adventurer, took up the invite. Things didn’t go quite as expected that July day in 1983. Heavy winds drove her balloon off course. “Where are you going?” people on the ground shouted up to her as she passed. “We don’t know!” Wynne shouted back. As it turned out, she and her pilot aborted the race on a golf course where their wicker basket overturned. A bit scary but no injuries.

That’s the thing about ballooning: You’re at the mercy of the elements. Such was the case in 1873 over Upper Bucks County. It was the day the village of Applebachsville had an unexpected and startling brush with a pioneering balloonist.

The tale begins earlier that April Fool’s day in Reading, about 45 miles away. Professor Washington Harrison Donaldson, 33, prepared to ascend in a hot air balloon called an “aerostat”. As the “aeronaut” pilot, he was an accomplished gymnast, ventriloquist, magician and tight rope walker. In 1862, he stretched a rope across the Schuylkill River, crossed over, returned to the center and dove into the river from 90 feet high. Later he crossed the Genesee River at Rochester, N.Y. while pushing a man in a wheelbarrow. Always the showman, he informed an audience on one occasion he was too sick to perform. Instead his wife would walk the rope. Soon a woman in a fancy hat appeared on the line, doing a slow striptease. Getting down to her bare essentials, she let them drop to reveal Donaldson in tights.

In 1871 he took possession of a bartered hot air balloon. Without instruction, he inflated it with heated coal gas and soared away on an 18-mile flight. If his balloon could reach 3,000 feet or more, he reasoned, a steady west-to-east wind could enable him to be first to cross the Atlantic. More test flights were needed. Among them was the April 1, 1873 ascension.

At 2:45 p.m. a large crowd gathered in Reading to see Donaldson lift off in his “car” (basket) dangling below a canvas balloon measuring 25 feet in diameter. The craft bobbed around in thick clouds, losing sight of the earth and reaching 11,000 feet. The aeronaut could hear water running in swollen rivers, train whistles and railcars rumbling over tracks unseen. An hour into the flight, it started to rain. Then hail. Temperatures dipped to 20 degrees. Donaldson needed to land. Through a break in the clouds he spied Applebachsville. There someone with keen eyesight noticed a speck in the sky. At first no one could make it out. The speck grew. Was it a kite? Or perhaps a paper balloon that village boys sent up? As the local newspaper reported, “No one, at the dizzy height at which it was first seen, had any thought that it contained a human being.”

Witnesses finally made out the pilot. The massive apparition floated into view 75 feet overhead, aiming for Gideon Wells’ farm field. Donaldson lowered a drag line which hooked the roof of the schoolhouse, peeling away shingles. The clatter caused a stampede inside. Town folk grabbed the rope, enabling Donaldson to scramble to the ground, grateful and triumphant. Amid the awed gathering, he deflated the balloon, folded it and arranged transportation back to Reading.

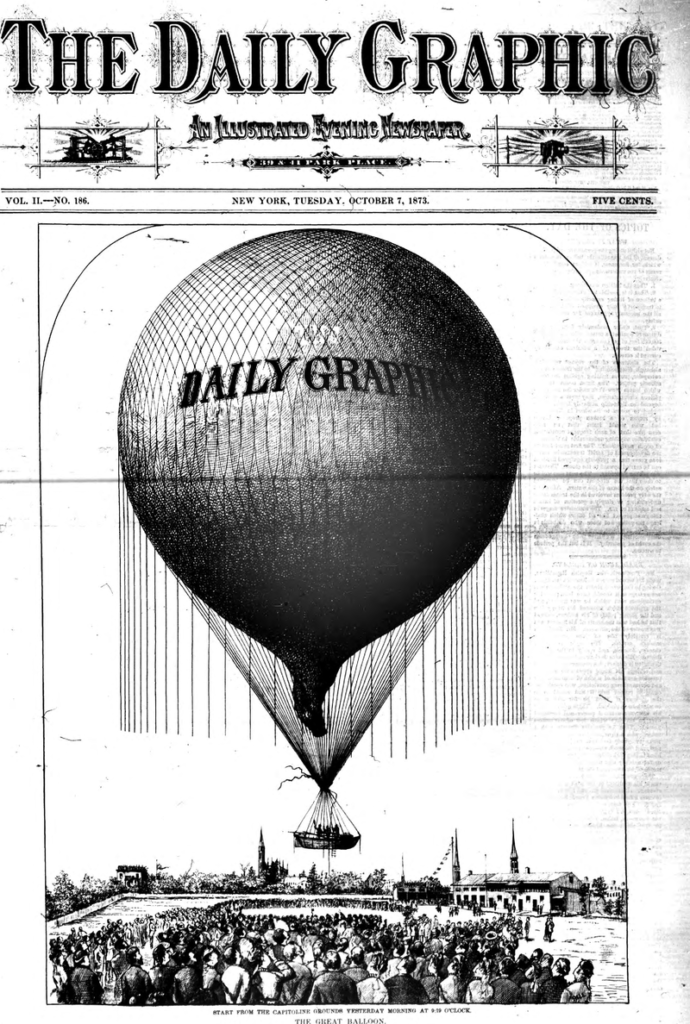

People in Applebachsville would follow Donaldson’s escapades in the newspapers. Six months after his village landing, he convinced the publisher of New York City’s Daily Graphic newspaper to underwrite the cost of a mammoth balloon to attempt a trans-Atlantic crossing. On Oct. 7, the balloon ascended from Brooklyn with a lifeboat doubling as a control basket for Donaldson and two companions. The boat was filled with provisions in case the men had to abort over the ocean. One hundred miles into the adventure, they lost control of the ungainly craft that smashed into trees in Connecticut, killing one of Donaldson’s companions.

Promoter P.T. Barnum the following year hired Donaldson who toured the nation, taking passengers on short flights. On July 15, 1875, he and a Chicago Evening Journal reporter took flight over Lake Michigan. Thirty miles offshore, fishermen reported the balloon flying low, dragging its wicker basket through the wave tops. When someone was washed overboard, the balloon made a steep ascent and disappeared into a violent storm. The following day, the reporter’s body washed ashore. Donaldson and his balloon were never found.

The professor’s dream of an Atlantic crossing would remain unattainable until 1978 when the helium-filled Double Eagle II with three pilots achieved it.

Sources include “Donaldson, Washington H.” by James Grant Wilson published in 1900 in Appletons’ Cyclopædia of American Biography; and “Landing of a Balloon in Haycock” by the Daily Intelligencer dated April 1, 1873. Also a tip of the hat to the Buckwampum Historical Society.