Of homeopathic medicine, folk remedies and the great Lenape Indian Chief Nutimus.

My first encounter with folk medicine was on a childhood vacation to Puget Sound in Washington. We stayed with my mother’s Norwegian parents on their farm near the village of Olalla. Mom was one of 9 siblings, most of whom lived nearby. I was about 10 and playing with all my new-found cousins fishing in creeks and having fun in the barn. Maybe because of the high humidity, I contracted an excruciating earache. No doctor was available. So Aunt Bernice asked me to pee into a metal cup she handed me. Say what!? Too much in pain to debate the issue, I did what she asked in privacy. She then took the cup to the stove, heated or boiled it (I didn’t see her), cooled it a bit, then brought it back to me. With an eye dropper she proceeded to drip the fluid into my ear. Wow! Earache vanished in minutes. And I still can hear.

Years later a member of my family contracted thrush. A variety of prescription drugs made no headway. So I reached into the folk medicine archives and discovered an ancient treatment that looked promising: unfiltered apple cider vinegar. The illness vanished within 24 hours.

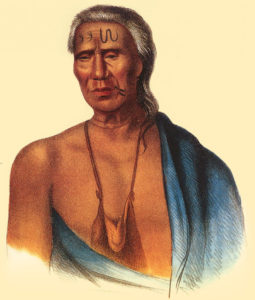

Pharmaceuticals certainly have their place these days. But not so much in olden times. Which brings me to the story of Nutimus, the famous Lenape Indian “medicine man” of the early 1700s. He relied on roots and herbs to cure life’s ills. Much in demand by both Native Americans and colonists, he lived in the rugged wilderness of Nockamixon in Upper Bucks County. He responded to medicinal needs both here and across the Delaware River in New Jersey where he was born. He was famous as a gifted healer, blacksmith and pacifist chief of the tribe’s Turtle Clan in Lenape nation spanning the lower Delaware Valley.

Among legendary intercessions by Nutimus was saving the life of settler William Satterthwaite after he was bitten by a rattlesnake on a hill above Lumberville in Solebury. The poet was in excruciating pain by the time the chief reached him. Using an herbal calamus root compound, he restored Satterthwaite to health, warning him to stay off the mountain. The ability of healers like Nutimus astounded Europeans. “The Indians know how to cure very dangerous and perilous wounds and sores by roots, leaves and other little things,” reported New York lawyer Adriaen van der Donck in 1659.

Locating medicinal ingredients was crucial. For instance, Indians knew today’s well-known Buckingham Mountain near Lahaska as “Pepachganking”. It meant “at the place of the calamus root.” The 3-mile-long mountain was a defacto Rx dispensary for calamus. Internally, it could be used to treat ulcers, gastritis, diarrhea and flatulence. As a topical skin ointment, poison ivy, poison oak and other irritations. The plant relaxed muscles, brought on sleepiness and could reduce swelling, perhaps kill cancer. It also repelled and killed insects, important when living in the woods.

The trick was dosage. A bit too much was toxic. This hand-me-down knowledge was mysterious, elevating those like Nutimus to spiritual leaders of their tribes. One of the most famous was Tatanka Iyotake (Sitting Bull), a Sioux medicine man and tribal chief best known for his victory over the American cavalry at the Battle of Little Big Horn. Nutimus was hardly a warrior however. He knew William Penn and it was with him that tribal peace endured for 50 years. That tradition inspired artist Edward Hicks of Newtown to paint his celebrated “Peaceable Kingdom” masterpieces.

Nutimus often traveled with his daughter who was conversant in English unlike her dad. On their visit to settler Edward Marshall’s home in Tinicum, she suffered a rabid dog bite. Nutimus directed Marshall and others to build a narrow trough into which the chief placed his daughter, bound tightly. Nutimus then spread a warm mixture of herbs and roots over her, covering all but her face. There she remained for a few days. Miraculously the fever lessened, her respiration returned to normal and she recovered. It was “a perfect cure using the herb Seneca snakeroot,” reported historian William J. Buck in 1855.

Snakeroot. Medicine men like Nutimus knew it was a cure for inflammation, croup, the common cold, bleeding wounds, sore throat and toothache. Nutimus’ knowledge of such wonders eventually faded into history. So too has Buckingham Mountain’s reputation as a source of calamus root. I’m convinced it still grows there having seen the stalks on the hillside when we lived nearby. But did the Indian name – pepachganking – really describe calamus? As in all aspects of history, other points of view come into play. Dr. Amandus Johnson in “Geographia Americae” who studied the Lenape in the 1600s wrote “pepachganking” should be spelled “Papchesing” with a different meaning:

“At the place of the woodpecker.”

Sources include “Place Names in Bucks County Pennsylvania” by George MacReynolds published in 1942; “History of Bucks County” by William J. Bucks published in 1855 and “Geographia Americae with an Account of the Delaware Indians Based on Surveys and Notes Made in 1654-1656″ by Peter Lindestrom (translator) published in 1925.