The servants’ township, discovering cannonball polish and a proxy wedding.

What makes the study of history interesting are all the odd stories and place names that characterize wherever you are. Bucks County certainly has more than its share. That’s what 330 years of history will do for you. Take for instance a picturesque area on the west side of Upper Bucks County.

“Servants Township” in Hilltown

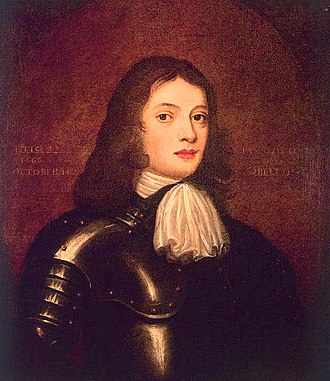

When Hilltown was formed in 1722, a document filed in county court listed its ill-defined northern frontier as “The Servants Township.” It was a rocky, hilly wilderness almost no one was interested in. Pennsylvania founder William Penn thought it’d be ideal for indentured servants once they earned their freedom. At the time, almost half of European immigrants in the 13 colonies were indentured servants. Penn viewed them as pioneers when their terms of indenture were up. They could relocate to the land he set aside in Pennsylvania and make the best of it as free people.

Servants Township posed a problem to German settlers of neighboring Richland Township. They complained about the lack of road maintenance through the reservation, and suggested county court declare it an official township to help focus government resources. The judges agreed but changed the name to less ignoble “Rockhill Township” in 1740. Later it was subdivided into today’s East Rockhill and West Rockhill townships.

Proxy wedding in Bristol

Stately homes on Radcliffe Street along the Delaware River in Bristol have long been the No. 1 address in town. In 1809 the King of Spain posted Spanish Minister Don de Onis y Gonzalez-Vara and his family to one of the estates. Onis and his wife were charming and fit nicely into the social fabric of old Bristol.

Though matters of state were important to Don de Onis, something else was foremost on his mind in 1816: the upcoming wedding of his eldest daughter to a Spanish army officer. Narciss and younger sister Clementina were extraordinary beauties who often drew attention strolling the walkways around their estate with their governess. Narciss liked to paint scenes of the house and gardens to send back to Spain to show friends what life was like in America.

As the date for the wedding in the bride’s home fast approached, the groom suddenly was called to duty in Europe. With Narciss distraught, Daddy Onis suggested a wedding by proxy. So it was. The local newspaper called it “the strangest wedding ceremony ever performed.” Narciss’ father represented his intended son-in-law in Bristol. In Spain at the same noon hour, the groom’s sister stood in for Narciss. Father Hogan of the Catholic Church in Philadelphia performed the Bristol ceremony. “It was a grand affair and never before were so many grenadiers of Spanish blood in Bristol at one time,” reported the Bucks County Gazette. “Feasting and dancing were kept up till a late hour in the evening.”

Many Bristolians viewed the marriage as illegal since the groom wasn’t present. Love conquers all however. The wedding became a Spanish storybook tale, the bride and groom living happily ever after.

Cannonball polish in Feasterville

Frenchman Ralph Drackit in 1750 lived in a small house on Edge Hill in eastern Montgomery County not far from Feasterville. An acquaintance described him as “in low circumstances, but remarkable for ingenuity, intelligence and sagacity, an innocent and inoffensive man who was much in his element when plodding about in bye place alone, searching for something nobody else was looking for.”

Fortune smiled on Ralph on discovering a glittery black mineral on the property of a Feasterville farmer. Ralph recognized the stone as plumbago, a soft, aluable graphite quested after by warring European governments. Why? Because it could be used to polish cannonballs so they could be fired at greater distance with more accuracy. (Today it’s more commonly used as lead in pencils.)

Ralph decided to keep his strike a secret from farmer Naylor by digging at night and covering up the excavations before dawn. The graphite was easily cut, enabling Ralph to carry it home, smelt it down, then sell it in Philadelphia for export. Life was good.

Farmer John eventually noticed the ground disturbed in his cornfield. He lay in wait one night and surprised Drackit. The Frenchy confessed. John shrugged. “OK, go ahead. I don’t want the darned stone.” To which Ralph declared, “Sourire jusqu’aux oreilles!” Or something like that. Naylor and Drackit co-existed, the former living off corn, the latter off graphite. The years passed. Farm ownership shuttled through several owners until Robert Manson bought the acreage and resumed mining in the 1830s. He excavated the vein to a depth of 70 feet where ground water interceded. Over a three-year period, he cashed in his ore, sold to European customers for a $25,000 profit. That’d be $646,825 today. Eureka!

By 1840, the mine closed never to reopen.

Sources include “Episodes in Bucks County History” by George F. Lebergern Jr. published by the Bucks County Historical Tourist Commission in 1975; “Place Names in Bucks County Pennsylvania” by George MacReynolds published by the Bucks County Historical Society in 1942; and “Indentured Servitude in the 17th Century English Atlantic: A Brief Survey of the Literature,” by John Donoghue published in 2013 by History Compass.