Looking back on one woman’s 18-year crusade to create a juvenile justice system for Bucks.

There’s no statue nor portrait of Gertrude Bright to be found in Bucks County as far as I can tell. Her name is known to few. But if you measure the impact she had on the county’s judicial system, she would have few peers. In the midst of the Great Depression, she arrived with compassion for kids in trouble. In the crushing poverty of the 1930s, she not only sought justice for them in court, she personally helped where she could.

Bright, considered the “the Wonder Woman” of Bucks County in 1948, reflected on her challenge in an address to Doylestown’s Rotary Club in 1932. “I doubt whether many persons realize the terrible conditions that exist in many homes in the county – homes where the parents apparently fail to realize their responsibilities as parents toward their children.”

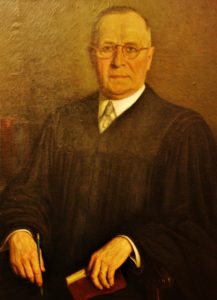

Lydia Gertrude Bright was the youngest of 10 siblings born to a wealthy Philadelphia couple. For 23 years, she worked for city social services and was a member of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. In 1930, Judge Hiram H. Keller of Bucks County Court recruited her. It had been his dream to establish a county-run juvenile detention home to keep youths out of the adult prison in Doylestown.

The judge must have been impressed on first meeting his new hire. Engaging and outspoken, Gertrude’s red hair was perfectly coifed and framed by fancy millinery plus a fur neck wrap that distinguished her. At middle age, she became the county’s first probation officer on Jan. 1, 1931. It was her role to create and manage a justice system for youths. She and the judge soon convinced the commissioners to purchase a spacious building across from the courthouse for a juvenile detention home. Bright opened an office and supervisory live-in quarters while workers remodeled the upper story into two rooms and two baths for kids ages 10 to 18 formerly held in the prison. Many other youths remained in various institutions, foster homes or with their families under Gertrude’s supervision. She had direct influence on all the them – 97 boys and girls in her first year, 250 by 1939 and 514 by 1946.

She made it policy that every child receive a Christmas gift annually. “When I was in Philadelphia,” she explained in 1934, “I used to do Christmas shopping for 500 children. I used to begin in November by tackling the wholesale places for bargains.”

As “Mrs. Santa Claus” in Bucks, she encouraged charity drives and persuaded the commissioners to pay for purchases. Mountains of donations annually filled a Doylestown stockroom that “resembled a department store,” noted one newspaper. Boxes of candy, new clothes, gloves, caps, bedroom slippers, school bags, umbrellas, mechanical gadgets, books, toy wheelbarrows, trucks, doll cradles, carts, animals on wheels, bunny-rockers and much more. All helped “carry out the Christmas spirit,” as Bright proclaimed.

She remained accessible, either at her private Doylestown home, her office or representing clients in court. She was known as delightfully witty while never “overplaying her hand” during court testimony, according to newspaper columnist Lester Trauch who covered her. She also traversed the county, checking on families and youths in jeopardy.

When a fire broke out at a Doylestown foster home on Sept. 21, 1945, Gertrude rushed to the scene. Salome Rickert, a practical nurse employed to care for seven infants, tried desperately to save the children. With her dress aflame, she carried one to safety on the porch before she collapsed and died. Gertrude gathered up five survivors and ushered them home with her. There they stayed until future care could be arranged.

Given the rigors of her job, Bright still found time for other interests including theater, opera and the symphony orchestra. Never married, she raised two nieces and a nephew. As a member of an Episcopal church in Philadelphia, she believed pointing children in the direction of religion helped lift them out of delinquency.

Despite failing health in 1948, Gertrude remained employed. After work on March 4, 1950, she succumbed to a heart attack at home while reading a newspaper. In his eulogy, Judge Keller summed up her legacy. “Our juvenile court system of which we are very proud was largely organized by Miss Bright. She was indefatigable in her labors and her efforts and had excellent judgement. We cannot pay too much high regard and respect to her memory and the fine work she did.” The Intelligencer noted she was “beloved by scores of Bucks countians, including wards, orphans and mothers for whose welfare she was responsible.”

What Gertrude Bright started in 1931 now encompasses four departments of county government – Domestic Relations, Juvenile Probation, Children &Youth, and the Bucks County Youth Center. What was once a one-woman operation today requires nearly 200 employees managing 10,650 cases annually.

Thanks to Brian Boger, a supervisor at the county’s Youth (detention) Center, and Larry King, public information officer for Bucks County government, for tipping me off to the remarkable life and times of Gertrude Bright. Boger, while working on a formal history of the youth center, reached out to me to tell Gertrude’s story and provided much research assistance.