The man with the longest name in Bristol history gave us Florida.

In my early 20s and living in Florida, I frequently visited St. Augustine, the oldest European settlement in the contiguous United States. Spanish explorers founded it in 1565 on the northeast coast. The city was my closest brush with how I thought the architecture of southern Europe might look like.

After moving to Bucks County in the 1970s, I discovered a most unusual fact: The man with the longest name in Bristol history gave us St. Augustine and all of Florida. I mentioned Don Luis de Onis y Gonzalez Vara Lopez y Gomez in a previous column for the controversial proxy wedding he arranged for his daughter at his home on Radcliffe Street in 1816.

It’s what came long after the wedding that made Don Luis a major historical figure. He was born in 1762 in Salamanca, a repository of wealth, culture and education in western Spain. The son of a nobleman, he learned Greek and Latin by age 8 and earned his law degree at 16. He then embarked on a government career that took him to various Spanish embassy posts in Europe. He also negotiated the 1802 peace treaty with France that calmed Napoleon’s threat to invade Spain. The emperor did so anyway just six years later, imprisoning King

Fernando VII and installing brother Joseph as the new king.

Spain’s exiled government directed Onis to sail to the United States in 1809 to persuade President James Madison to recognize Fernando VII as the only legitimate ruler of Spain. Madison, however, refused to give Onis diplomatic status unless and until Napoleon lost his grip on Spain. Onis had no alternative than to wait. In the meantime, he and his family moved to Bristol where they brought “wealth and respectability” to the tiny town, according to local historian George F. Lebergern Jr.

Onis secured a well-landscaped Colonial manse for the family home two blocks from the center of town. Onis, his wife, two daughters and a son became social fixtures. Bristolians often saw the envoy with his regal bearing strolling his property with daughters Narciss and Clementina, viewed as extraordinary beauties. The multilingual diplomat quickly absorbed local customs, becoming keenly interested in Bristol’s Masonic Brotherhood. At the time the borough hosted more secret societies than any other municipality its size in the U.S. Among more than two dozen were the Order of Red Men, Knights of Pythias, Ancient Order of Hibernians, Knights of Columbus, Order of Elks, Woodmen of the World and Degree of Pocahontas. Bristol Lodge No. 25 of the Ancient York Masons was perhaps the most influential, counting among its membership many prominent Bucks County citizens including John Fitch who invented the steamboat. Onis became intrigued by the Masons’ commitment “to make a good man better” regardless of religion and joined the order.

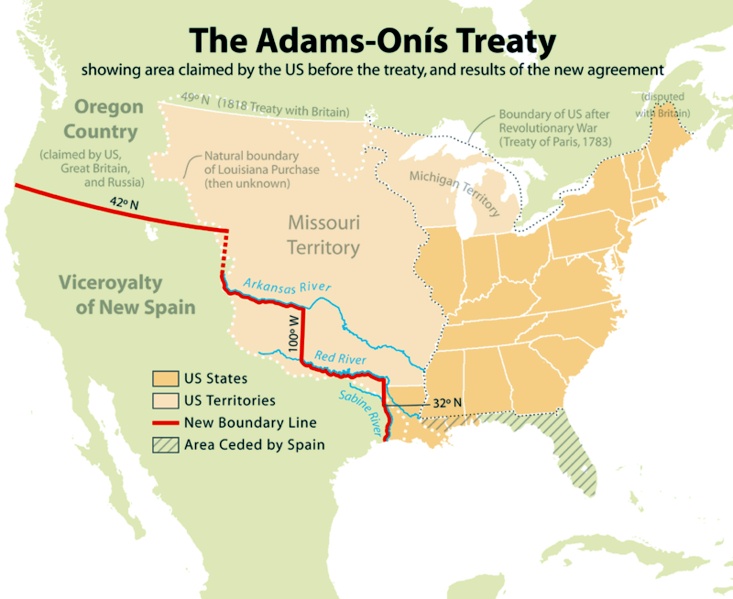

While absorbing life in Bristol, the envoy remained focused on Spain. He worked out of the Spanish consular office in Philadelphia, railing against attempts by Americans to illegally occupy Florida. There was confusion over the border of the Louisiana Purchase from France obtained by Thomas Jefferson. Americans believed Florida and east Texas (than known as the New Philippines province of the New Spain) were part of that purchase. Besides this thorny issue, Onis fretted over American mercenaries fomenting revolution in South America. Under the pseudonym “Verus” (Latin for “true”), Onis published pamphlets justifying Spain’s rule over its American colonies.

In 1815, good news finally arrived for the beleaguered Don Luis. Napoleon’s army had been defeated at the Battle of Waterloo. Joseph Bonaparte had abdicated the Spanish throne and fled to Bordentown, N.J. Meanwhile, King Ferdinand was restored to the throne.

Onis now had official cache with President Madison. As ambassador, Onis began difficult negotiations with Secretary of State John Quincy Adams to settle the Florida-Texas issue. Adams found Onis to be a staunch adversary: “Cold, calculating, wily, always commanding his own temper, proud because he is a Spaniard, but supple and cunning, accommodating the tone of his pretensions precisely to the degree of endurance of his opponent, bold and overbearing to the utmost extent to which it is tolerated.”

After four years, the two finally reached a deal. In the resulting Onis-Adams Treaty of 1819, Spain relinquished Florida. Onis obviously thought it a lost cause. In return the treaty codified that Texas was part of New Spain. The U.S. had no right to any of it.

After four years, the two finally reached a deal. In the resulting Onis-Adams Treaty of 1819, Spain relinquished Florida. Onis obviously thought it a lost cause. In return the treaty codified that Texas was part of New Spain. The U.S. had no right to any of it.

His work accomplished, Onis and his family returned to Spain. That wasn’t the end of the story however. In 1846 the U.S. invaded newly independent Mexico (the former New Spain) to snatch away one third of that country – Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada and California. Had not that happened, imagine what Mexico might have become with California’s gold, Nevada’s silver and the oil riches of Texas.

Sources include “200th Anniversary History of Bristol Lodge No. 25 F.&A.M.” by Lodge past master George F. Lebegern Jr. published in 1980; “Onis, Luis de” from University of Miami Library at http://scholar.library.miami.edu/purdy/onis2.html; and “Adams-onis Treaty” by Ralph Blodgett, Oklahoma Historical Society.