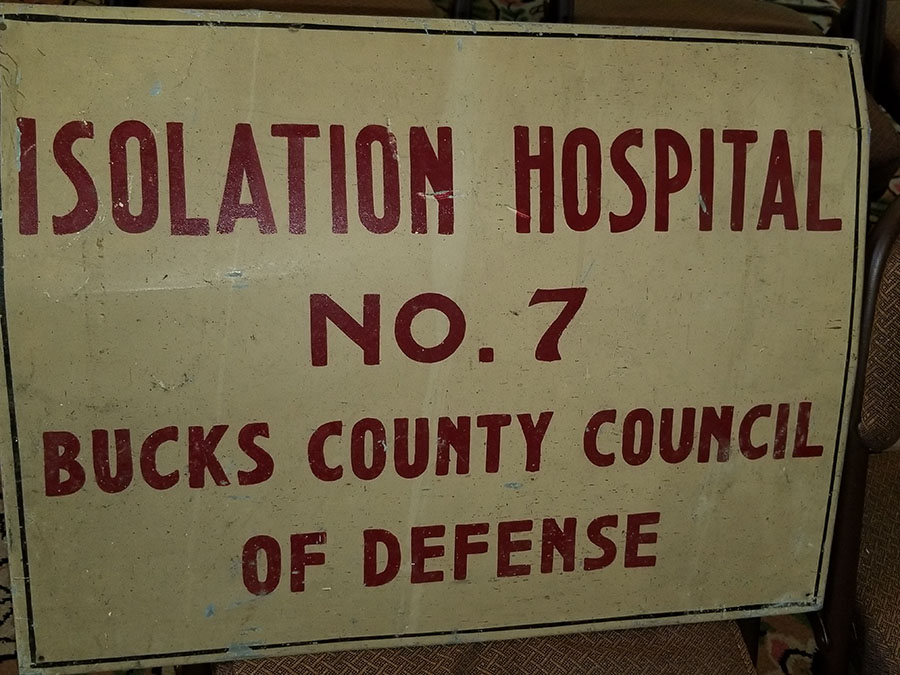

A old sign found in a Bucks attic is a reminder of today’s pandemic.

Like most of us, Kathy Horwatt is hunkered down at home on orders from Gov. Wolf. Her pandemic isolation in Langhorne reminds her of what the Four Lanes End Garden Club discovered in the attic of the town’s most historic house a few years ago. The club was rooting around for holiday craft materials when member Trisha Gorman found an old sign reading “Isolation Hospital No. 7″ and “Bucks County Council of Defense”. Trish gave it to Kathy, a long-time borough councilwoman, to show to school kids. She wondered whether the house at the corner of Maple and Bellevue was a hospital in the worst pandemic in human history. After all it was headquarters for the Bucks County Red Cross during the 1918 Spanish Flu crisis.

The Richardson House has quite a legacy in its 281-year history. Ben Franklin and John Hancock once were customers in its ground-floor store. The house and grounds quartered George Washington’s officers and Hessian prisoners after the Battle of Trenton in 1776. It’s where the Marquis de Lafayette received treatment for war wounds. Red Cross nurses conducted blood drives there during World War I. It was the center of “Welcome Home” ceremonies for returning soldiers. But was the houses an isolation hospital at the time? Kathy suggested last week I look into it. I did.

What impresses me is how similar the pandemic of 1918 was to what we’re experiencing in 2020.

Most historians believe the former began in January 1918 among U.S. troops in training in Haskell County, Kansas. They contracted a deadly swine flu emanating from local hog farms. The severity alarmed attending Dr. Loring Miner who warned area colleges and the U.S. Public Health Service to prepare and alert the public. They didn’t. The flu spread to other training bases and then to Europe with the arrival of American troops in World War I. With the U.S. mum about the contagion, it spread slowly before clobbering Spain with a higher than normal death toll in the spring. That got the world’s attention, giving the pandemic its name – Spanish Flu. Spain was far away and U.S. authorities lost concern when summer heat seemed to end the crisis.

In early September however, a Navy ship arrived in Philadelphia with troops infected by a mutated, stronger version of the virus. After two died, Richboro-born physician Wilmer Krusen was dismissive. As director of Philadelphia’s Department of Public Health, he downplayed the threat as typical seasonal flu. Other doctors were alarmed. They asked Krussen to cancel the city’s October parade. He refused. The physicians sent letters to newspapers advising residents not to attend. None were printed.

The parade drew 200,000. Three days later 635 contracted the flu; 116 died. The speed and course of the second-wave virus sent shock waves: Great fatigue, fever, headache, violent coughing that ruptured lung tissue and tore abdominal muscles, victims turning blue in severe cases, bleeding from the mouth, nose and ears, followed by death. Most were adults from age 20 to 50. Sons and daughters of older parents perished, many within hours. Authorities struggled to care for surging orphans. Schools and businesses closed. Telephone, mail and garbage collections ended. Bodies piled up; too few coffins, morticians and grave diggers. Citizens made gauze face masks to be washed daily and saturated with zinc sulphate solution. Medical advice included wearing “good warm woolen underwear, and running quickly when you hear a sneeze.” In Chicago, police arrested anyone sneezing without a handkerchief.

A quarter of the U.S. population became infected that fall, making it almost impossible to escape the virus. In lightly populated, mostly rural Bucks, the government closed public facilities and advised non-essential businesses to do likewise. Public gatherings were banned. In two months, 9,500 contracted Spanish Flu with many deaths. Henry Krup, a Mennonite deacon in the Perkasie area of Upper Bucks, made diary entries. “Oct. 4 – Many people are dying from influenza. Oct. 5 – Annie Nyce was buried at Franconia, age 18. Oct. 19 – Funeral of Edwin Keeler of Souderton, age 39. Oct. 27 – I hope this is the last Sunday without church services.”

The emergency continued into November before the epidemic eased its grip. One third of the world’s 500 million people had suffered; more than 50 million perished. In the U.S., 22 million got the virus. At least 675,000 died. By December, both the war and the epidemic had come to an end. People were exhausted. They just wanted to forget. Noted the Mennonite Heritage Center in Harleysville, “It seemed like the sickness and death of October 1918 were largely forgotten, at least by the news media.”

The question remains: Were there isolation hospitals in Bucks during the pandemic? It’s unclear. However, online articles I retrieved from the Bristol Courier and the Central News of Perkasie indicate the Bucks County Council of Defense came into being on April 28, 1941 – 7 months before the U.S. entered World War II. County government in conjunction with the Richardson House-based Red Cross developed a master preparedness plan with expectation of enemy attack. Plans included identifying locations for isolation wards, perhaps the Richardson House. After the war, the sign for “Isolation Hospital No. 7″ was stashed in the attic for the garden club to find 73 years later.

In terms of isolation today, deja vu.

Sources include “Outlines Work Done by the Defense Council” published on Aug. 28, 1941 in the Bristol Daily Courier; the newsletter “Twenty Eight-Two”, Fall 2018 issue published by the Bucks County Health Department; the Mennonite diaries found on the web at https://mhep.org/the-flu-epidemic-of-1918-accounts-from-local-diaries/, and

“Philadelphia Threw a WWI Parade That Gave Thousands of Onlookers the Flu” by Kenneth C. Davis published on Sept. 21,2018 in Smithsonian Magazine.