How clover got to Upper Bucks, a whale visits Bristol and a deadly pistol duel for love.

If you’re able to pluck a 4-leaf clover for good luck on St. Patrick’s Day in Upper Bucks, you might want to thank 12-year-old Isaac Burson of Springfield Township. It was on April 25, 1852 when his father sent him on a special mission to Lower Bucks. He was to seek out John Stapler of Lower Makefield. The reason: Buy from Stapler one bushel of Red Clover seed for $40.

In a sense, young Isaac became the Johnny Clover Seed of Upper Bucks that day. Returning home with his purchase, he and his father promptly planted the seeds on 10 acres of the family farm. Pop knew one thing about clover: It produces nitrogen, fixed in the soil so that follow-up crops of hay grew like no other. In fact, his acreage produced 22 large loads of hay that first year. No other farm got more than one bushel on 10 acres. It was magic.

When word spread clover was the reason, spectators flocked to the farm to see it grow. According to an eyewitness account, “The fence around the field on some days was lined with spectators. All viewed it with that curiosity natural to persons at first beholding a novelty, or a beautiful production in the vegetable world on which they gazed with wonder and delight for the first time. From this originated and spread all this variety of grass in the upper section of the county.”

Occasionally a four-leaf clover can be found. A sign of good luck? A book published in London in 1869 declared four-leaf clovers were “gathered at night-time during the full moon by sorceresses, who mixed it with vervain and other ingredients, while young girls in search of a token of perfect happiness made quest of the plant by day.” Eight years later an 11-year-old girl wrote a letter to St. Nicholas Magazine, a popular American children’s monthly. She asked, “Did the fairies ever whisper in your ear that a four-leaf clover brought good luck to the finder?”

I’ll have to remember this the next time I join Margaux, 5, and Dashiell, 9, in a field of clover near their home in Upper Bucks.

Citizens in Lower Bucks marveled at a different sort of wonder back in the day: A giant whale in the Delaware River. The excitement occurred on April 22, 1861. We pick up the story as reported in Bache’s Index:

“Our citizens were treated to a free exhibition and some of the more hazardous and lively sport, by the appearance of a black whale in the Delaware on Monday last. His whaleship passed up and down the river between Burlington and for a short distance above Bristol, several times, spouting a stream of water several feet high. Our sportsmen with the oar succeeded in nearly shoaling him several times, and once had him for a time fast with a harpoon, from which both it and they more luckily escaped being taken. It was eventually captured on Tuesday near Kensington. It was said to be about 46 feet long.”

At that length, the creature was likely a humpback whale.

In 1798, the 10th Regiment of the U.S. Army was encamped on farmland outside Bristol. One day someone broke into an out building containing farmer John Booz’ whiskey still. A barrel of the oh-be-joyful was stolen. Booz blamed soldiers and complained to Capt. Sharp, the commanding officer. He promised to investigate. Unfortunately, love interceded.

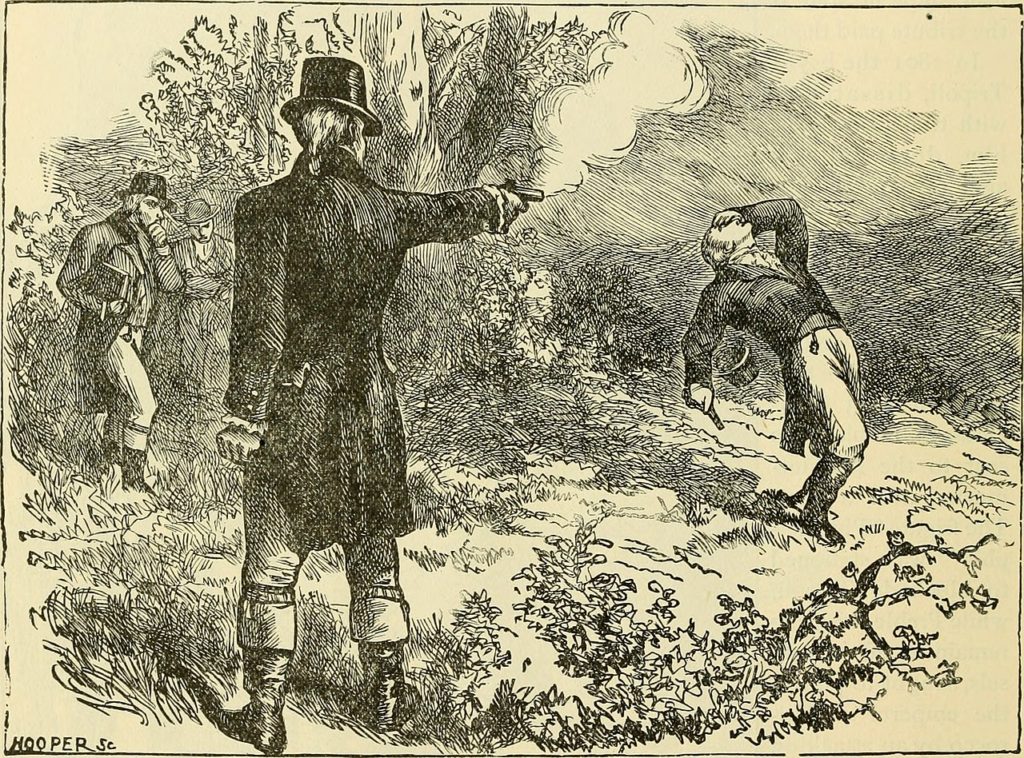

The commander had fallen for local Irish lass Miss McElroy. She also was the object of affection of Army quartermaster Johnson. Things got testy. Sharp challenged Johnson to a pistol duel to settle the matter. Miss McElroy pleaded with the captain not to engage Johnson. But Sharp told her to fear not, nothing would happen to him.

The two men faced off above Adams Hollow Creek not far from present day St. Mark’s Church on Radcliffe Street. Sharp fired prematurely, missing. Johnson beseeched his captain to withdraw his challenge. When Sharp refused, Johnson took aim and fired. The captain was dead on arrival at a nearby boarding house. Johnson fled to Virginia, abandoning his flirtation with Miss McElroy who never married.

Meanwhile, the mystery of Mr. Booz’ stolen booze remained unsolved. Eventually a man in Ohio confessed he and fellow soldiers made off with it and buried the barrel near a creek he named but not the exact location. In the days to come, according to Bristol historian Doron Green, “Many lovers of good whiskey, with a rod of iron sharpened to a point, made diligent searches by probing the ground on both sides of the creek. If the long-sought for barrel is ever found, it would be well for the finder to drink sparingly of its contents.”

Sources include “How Clover Came to Upper Bucks” published in January 2010 in “Penny Lots”, newsletter of the Bucks County Historical Society; “Vegetable Teratology: An Account of the Principal Deviations from the Usual Construction of Plants” published in 1869 by Robert Hardwicke in London; and “A History of Bristol Borough” by Doron Green published in 1911 in Camden, N.J. and available at the Grundy Library in Bristol.