Here’s why the historic Delaware Canal periodically dries up below New Hope.

A month ago, all was picturesque on the Delaware Canal from New Hope south to Bristol. Fish jumping, turtles sunbathing, Canada geese plying about and great blue herons perched on the shoreline. People were jogging, biking and hiking with four-footed companions while enjoying the early fall foliage. But then something strange happened. The waterway dried up. Below Morrisville, the scene transformed from idyllic sky and water to a parched desert landscape akin to West Texas. Did someone punch a hole in the basin?

I turned to my Delaware Canal docent for an explanation. Susan Taylor is executive director of the Friends of the Canal, volunteer guardians who work closely with officials of the 60-mile-long Roosevelt State Park to maintain and enhance the 192-year-old canal. Lately the Friends have added illustrative markers alongside the canal to emphasize its history as a shipping channel for mule-drawn, coal-laden boats from upstate Pennsylvania to factories in Bristol and Philadelphia during the Industrial Revolution. Today, the canal is a vestige of a vast network predating railroads in the Northeast. It remains the only canal still capable of being fully watered, the goal of the Friends.

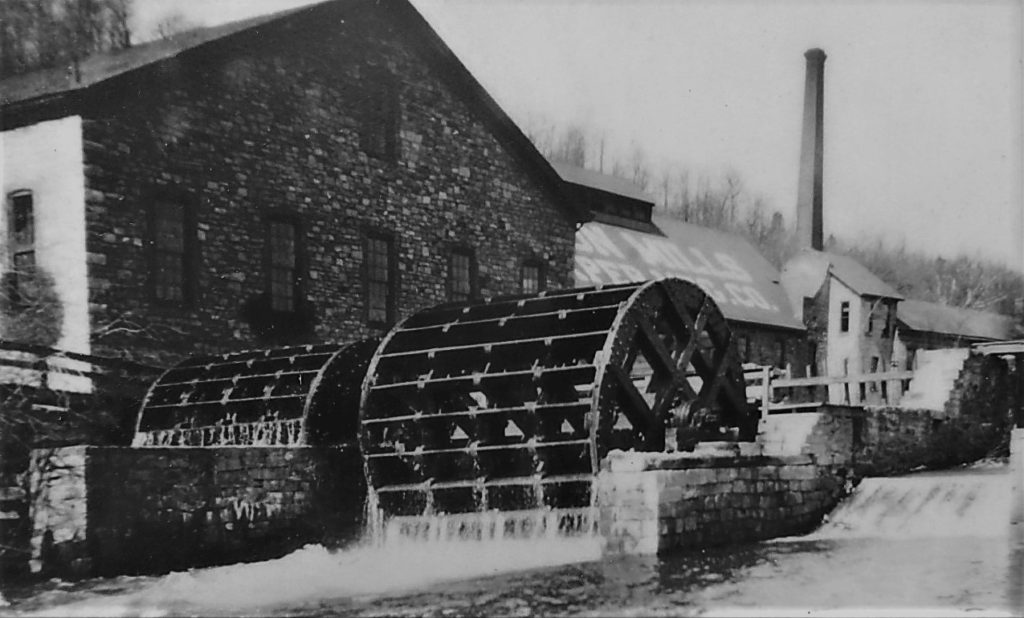

It’s no surprise to Susan the canal has dried up. The problem was anticipated when the big dig began on Oct. 27, 1827 in Bristol. Work paralleled the Pennsylvania shore to the Delaware’s junction with the Lehigh River in Easton. It was necessary to build 10 aqueducts over tributaries to the Delaware plus 23 large wooden locks to raise and lower water levels so canal boats could navigate from an elevation of 165 feet at Easton to sea level at Bristol. Water came from two sources: a lock on the Lehigh River and a freshly dug Delaware River inlet to the canal at New Hope. It was soon discovered the inlet behind the former Chez Odette Restaurant dried up whenever river levels dropped in late summer and fall. To solve that problem, giant water wheels were installed behind a new wing dam just downstream at Wells Falls. The wheels lifted river water into a conduit to the canal. That solved the issue for the next 100 years.

The canal closed in 1932, doomed by railroads and highways. State government took over and created Roosevelt State Park. Major recreation centers were to be developed at Yardley, Erwinna and Riegelsville. Nine smaller centers were to be spread out along the canal with canoe and boat concessions. Also in the planning were two dance barges, repair barges, tourism barges and cabin boats so families could plan canal vacations.

In 1934 however, a steel aqueduct carrying the canal over Tohickon Creek in Point Pleasant collapsed. Two years later a flood washed away a wooden replacement as well as the New Hope water wheels. Again the aqueduct was rebuilt. Other plans where put on hold as canal maintenance became a constant challenge. The locks ceased operation. New Jersey and Pennsylvania cooperated in restoring the wing dam in 1967 in hopes of a continued river flow into the inlet at New Hope. But no effort was made to re-establish the water wheels.

When the Delaware River is high, enough water passes through the New Hope inlet to maintain levels in the lower canal. But in late summer when the river drops, the supply is pinched. The result has given the canal a split personality. Upstream, property owners and visitors enjoy a well-watered, picturesque waterway year round. Below New Hope however, suddenly it’s the barrens of parched soil and rotting aquatic life for 25 miles.

What can be done?

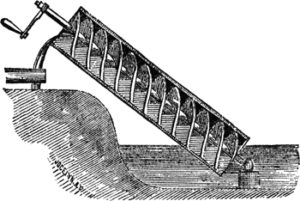

As a short-term solution, the Friends have acquired a pump to install on the edge of the river near Bowman’s Hill in the upper section of Washington Crossing Historical Park. Once a trench is dug for a pipe from the Delaware to the canal, the pump will siphon off river water in dry periods. The pump should be operational by next year. “It’s not a good solution,” according to Susan, noting it’s expensive to run at $1,000 to $1,400 a month. The Friends, who have agree to pay the electric bill, favor a more permanent solution: a pipe-enclosed Archimedes Screw between the canal and the river at the New Hope inlet that would provide a constant source of water. But that could cost $1 million.

Personally, I favor reinstalling water wheels to push water through the old conduit to the canal that now sits beneath luxury condos. The wheels would be attractive, historically-based and a unique way of preserving the canal as intended.

Sources include “Pennsylvania’s Delaware Division Canal: Sixty Miles of Euphoria and Frustration” by Albright G. Zimmerman published in 2002 by Canal History and Technology Press, Easton.