The infamous ‘Walking Purchase’ in Bucks fueled the Indian wars of the Wild West.

I grew up in California’s Central Valley where all the kids played “cowboys vs. Indians”, the latter being the bad guys. It was a manifestation of Hollywood movies portraying Native Americans as ruthless savages. Years later I was surprised to learn this stereotype had its genesis in Bucks County. The forced removal of Lenape Indians in the 1700s lit the fuse. Historians blame William Penn’s son Tom and James Logan of Philadelphia for whom the city’s Logan Square is named.

Let’s backtrack.

After Penn arrived from England in 1686 to establish Pennsylvania, he insisted on purchasing property at a fair price from the indigenous Lenapes. Grievances with settlers were to be resolved peacefully in a court of law, earning the tribe’s admiration.

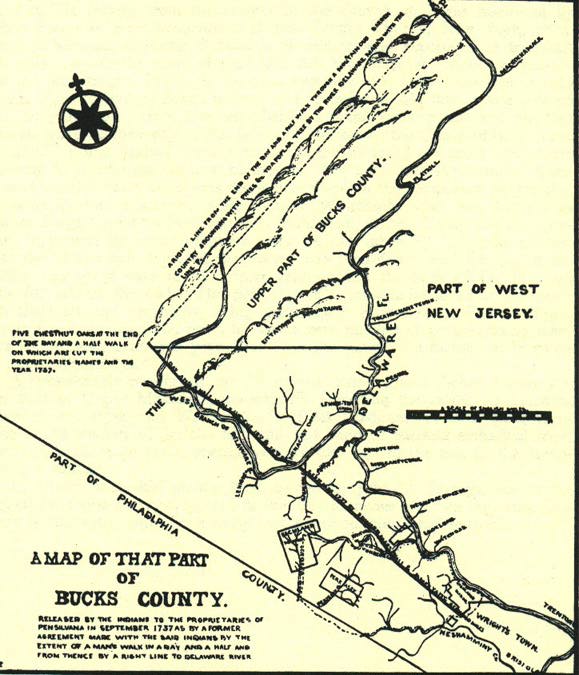

Following the death of Penn’s widow Hannah in 1726, eldest son Thomas arrived from London to govern Pop’s colony. He set out to remove Lenapes from Upper Bucks and the Lehigh Valley so he could sell the land. Helping was Logan, his father’s land agent, former owner of the Durham Iron Works in Durham Township, mayor of Philadelphia and chief justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Logan opened negotiations with the powerful Iroquois tribe of New York in belief it reigned over the Lenape. When the latter resisted, Logan fabricated a “lost” deed for the land executed 50 years earlier between the tribe and William Penn. Boundaries had yet to be set. To do so, the deed required a day-and-a-half walk northwest from Bucks County’s upper border in Wrightstown. The route would parallel the Delaware River and define the western boundary of the new territory.

To natives, the deed seemed fraudulent. It didn’t look typical. Signatures were unusual. Possible witnesses were long gone. Logan and Tom Penn paid no heed; the walk would begin. Logan recruited three English athletes with a promise from Penn to award 500 acres to the man covering the greatest distance. Logan’s associates secretly blazed a trail through the wilderness to speed the men. Logan also recruited three Lenape witnesses.

The walk began at sunrise on Sept. 19, 1737 in front of Wrightstown’s Quaker Meetinghouse on today’s Route 413. The county sheriff on horseback was official timekeeper. The Lenape anticipated a slow gait with rest stops on the first day. They believed the walkers might reach Tohickon Creek near today’s Lake Nockamixon, a distance of 24 miles. It took less than 3 hours. Indians denounced the “hurry walk”. Nonetheless, the trio pushed on. Ailing Solomon Jennings dropped out by noon. The two others reached the Lehigh River by afternoon and crossed in a boat below present day Bethlehem. They continued northwest, crossing the first ridge of the Poconos before camping for the night.

The quest resumed at 8 a.m. in the rain. Lenape observers left in disgust. Runner James Yates, a Newtown farmer, injured himself jumping a stream and couldn’t continue. That left Marshall who collapsed from exhaustion at 2:15 p.m. at a poplar tree near Mauch Chunk (today’s Jim Thorpe). It marked the end of the walk at 65 miles. A survey line established an 88-mile-long northern border of the “Walking Purchase” from the tree to the Delaware River above Port Jervis, N.Y. For Tom Penn, it was a 1,100-square-mile land grab the size of Rhode Island that vastly enlarged Bucks County. Penn got right to work selling tracts to surging European immigrants.

The Lenape filed suit in Philadelphia but lost despite the court noting fraud had occurred. As Lenape Chief Nutimus later put it, “We are no more brothers and friends but much more like open enemies.” Warriors responded with a wave of terror within the Walking Purchase. In two attacks on Marshall’s home in Tinicum Township, they killed his son, wounded his teenage daughter and kidnaped and killed his pregnant wife. Meanwhile Penn reneged on awarding Marshall any of the acreage promised.

With the odds stacked against them, Lenape families began relocating west. The last departed Bucks around Solebury’s Aquetong Spring, revered by the natives. In bitterness, many mentioned the Walking Purchase to justify future raids in frontier Pennsylvania. To end hostilities in 1756, chiefs of 13 Native American nations and colonial governors met in Easton to sign a peace deal by which Ohio would be protected as Indian country. It didn’t last. Seizure of Indian lands continued, igniting 150 years of conflict from coast to coast. In the end, eradication of Native Americans and Southern slavery left America with its two original sins.

In Bucks, few Lenape remained. Most were too old to move. People at Pennsbury Manor in Falls where William Penn once lived witnessed Lenape elders clinging to old walnut trees “with howling and lamentation, apparently frantic with grief, yet with wild enthusiastic fondness” for Penn whose son Tom and agent Logan had betrayed them.

***

Sources include “Promised Land: Penn’s Holy Experiment, the Walking Purchase, and the dispossession of Delawares, 1600-1763″ published in 2006 by the Lehigh University Press; “Thomas Penn’s Walking Purchase” by Watson W. Dewees published in 1912 by the Friends Historical Society of Philadelphia; “The Life of James Logan” posted by the Independence Hall Association at https://www.ushistory.org/penn/jameslogan.htm, and a biography of Edward Marshall at https