The man who gave Atlanta its name tried to extend the Delaware Canal into Philly.

In a sense, Bristol lucked out. That’s what crossed my mind as I followed a winding trail between Otter Creek’s tidal basin and the municipal parking lot. The basin once was the terminus of the Delaware Canal when it opened in 1832 and made Bristol a busy coal shipping port. As I walked past several historical markers, I was mindful of Albright Zimmerman’s detailed history of the canal. He pays close attention to a 19th century civil engineer who gave Atlanta its name and designed Pennsylvania’s famous Horseshoe Curve rail line. J. Edgar Thomson also mapped out a plan to extend the canal another 19 miles to Philadelphia’s seaport. It would have created a faster means of getting coal from upstate Pennsylvania to market. Had that occurred, Bristol’s coal-driven prosperity as a export terminal at Otter Creek no doubt would have been stunted. It nearly happened.

Let’s backtrack.

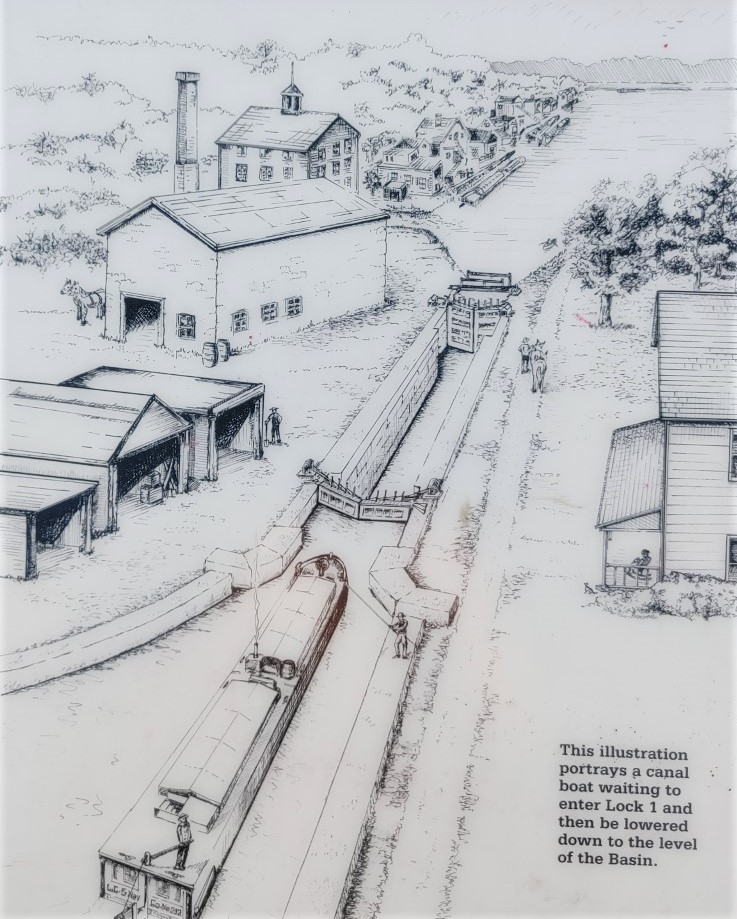

For 100 years, millions of tons of coal to fuel the region’s industrial revolution came down the Delaware Canal on mule-towed canal boats from Easton 60 miles away. After the long journey, the boats entered Otter Creek’s lagoon joining the Delaware River estuary. That basin once covered today’s vast municipal parking lot at the foot of the town’s Mill Street business district. Long piers extended through the middle of the basin to handle boats laden with anthracite, the purest form of coal in existence. From the basin, the boats were taken under tow by sailboats to Philadelphia and New Jersey ports. Bristol immediately experienced a surge of activity and prosperity. Many in the state Legislature, however, pushed for an extension of the “Big Dig” to Philadelphia’s deepwater ports. Was it feasible? At what cost?

To answer those questions the state canal commission in 1832 turned to 24-year-old civil engineer Thomson. He’s best known in his long career as a railroad surveyor, particularly for designing the famous Horseshoe Curve in Western Pennsylvania that enabled transcontinental railroad passage through the Allegheny Mountains. He also named the new city of Atlanta as chief engineer of the Georgia Railroad.

In Bristol he chose a canal route that would branch out from Lock 3 next to the Grundy clock tower and parallel Route 13 through Croydon, Andalusia and Northeast Philly. Four aqueducts would be built to carry the canal over the Neshaminy, Poquessing, Pennypack and Frankford creeks before reaching Kensington where the dig would turn east along Front Street to ports flanking the Ben Franklin Bridge. To ensure year-round water flow, Thomson proposed expanding water wheels on the Delaware at New Hope to divert sufficient flow into the canal for boats to reach Philadelphia.

Thomson submitted his findings to the Legislature in 1833. To backers, the plan seemed quite feasible. Over the next few years, numerous petitions (11 in 1838 alone) were introduced in both the state Senate and Assembly to get construction started.

A complication arose due to an invention by John Fitch of Warminster – the steamboat. He proved in 1787 that his paddle-wheel driven by a steam engine could make Delaware River travel fast and efficient in any weather. By the time the canal opened however, few steam tow boats plied the river. The Legislature passed a resolution in 1836 to hire one “until such time as the said canal shall be extended to the city of Philadelphia.” It noted a single steamboat at work on the privately-owned Lehigh Canal “has towed upwards of 1,000 tons of coal in 20 boats, all attached to her at the same time.” However state government declined getting into “the business of transportation” on the river.

In 1838, area legislators toured the proposed route of the canal extension and concluded it would jeopardize new mills, industrial buildings and many other improvements underway. Furthermore the price tag for the dig had soared to more than $1 million – equivalent to $30 million today. It was a stake through the heart of Thomson’s plan. The project also fell out of favor because steam-driven shipping was accelerating, making tow boats available to Bristol. That secured the borough’s future as the terminus of the canal until its closing in 1931.

Fast forward to 2021 and Bristol is in the midst of a town-wide rejuvenation. News arrived last month of a $1 million state grant to improve storm water drainage in the downtown business district and parking lot. Additional landscaping of Bristol’s riverside park, new lighting and beautification of the macadam trail edging what remains of the Otter Creek basin is contemplated.

All good. Still I think of what might have been for outdoor adventurers like biking pals Frank Williams, Mark Bogdan and I who have traveled the entire length of the canal from Easton to Bristol on its towpath. How cool would it have been to follow the extension from Bristol to Center City? Sigh.

***

Sources include “Pennsylvania’s Delaware Division Canal: Sixty Miles of Euphoria and Frustration” by Albright G. Zimmerman published in 2002 by the National Canal Museum in Easton, and help from Susan Taylor, executive director of Friends of the Delaware Canal support group.