The Ivy League university in New Jersey

has an historical link to Warminster and Warwick.

Princeton University always has been on my radar. As a kid, I envisioned enrollment in as an Ivy Leaguer. But my early college education detoured on scholarship to Cal/Berkeley in the 1960s when I was 17. It was no Princeton. The day I arrived dogs were sprinting freely around campus dressed in underwear. Huh? I was told students had slapped briefs on the canines to mock Berkeley City Council for passing an anti-obscenity ordinance.

After surviving a year in notorious Oxford Hall run by students, I left Cal for the University of Florida from which I graduated. On moving to Bucks County, I was as close as I had ever been to Princeton. Mary Anne and I in the early years of our marriage would learn to clog there. Our daughter would enroll in art lessons off campus and would graduate from high school at the university. Over the years, I would use the university library to research four books I wrote for the Naval Institute Press. On retirement and starting this weekly history column, the big surprise arrived: Princeton’s founding has a lot to do with a tiny church in Bucks County. This I had to look into.

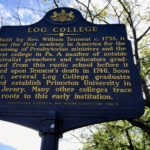

The trail led to William Tennent, an evangelical Presbyterian minister born in Ireland in 1673 and educated at Edinburgh University. In 1726, he arrived in Philadelphia to minister to Scotch-Irish immigrants in the rough wilderness along Neshaminy Creek in Warminster. Tennent founded the Neshaminy-Warwick Presbyterian Church in a particularly beautiful portion of the township that eventually became Warwick. With his four sons, the pastor built a single-room log school nearby to train his boys to become ministers.

Papa Tennent was a tough task master. The school day began at 5 a.m. and ended at 9 p.m. The regimen was austere – non-stop instruction and study with a heavy emphasis on Hebrew, Greek and Latin (which Tennent spoke fluently).

Before long, more young men enrolled, living in the school’s second-floor attic or boarding at the Tennent home. Meanwhile, the “excitable” zeal of Rev. Tennent’s “New Side” sermons drew the scorn of “Old Side” members of Philadelphia’s Presbyterian Synod of North America, a schism that would grow. The synod would only accept ministers trained at Harvard, Yale or schools in Europe – effectively disqualifying Rev. Tennent’s graduates. Old Siders scoffed at his school as well, derisively calling it “Log College.”

Nevertheless, the school persevered amid a “New Awakening” religious movement in the 1730s. Tennent was in the vanguard along with touring English preacher George Whitefield. In 1739, Tennent invited the 24-year-old phenom to address his congregation. More than 3,000 people flocked to hear the dynamic minister whose power of oratory made him famous. Benjamin Franklin calculated Whitefield could easily be heard from an outdoor stage by as many as 30,000 people.

In 20 years, Log College graduated about two dozen students. The first 13 including all of Tennent’s sons became ministers who established their own far-flung divinity schools. Among 51 colleges that stem from their missions are Lafayette, Illinois, Davidson, Austin, Dubuque, Western, Albany, Trinity, Hamilton and Lake Forest.

Log College closed in 1746 with the death of its patriarch. That same year its successor came into being – the College of New Jersey. State government granted the synod a charter to open the school based on principles taught at Log College. Like Harvard and Yale however, the college was to focus on liberal arts and science, not just theology. Log College alumni Samuel Blair, Samuel Finley, Richard Treat and two of Tennent’s sons, Gilbert and William Jr. were named to the 12-member charter board of trustees. Gilbert traveled to England where he raised enough money to construct the college’s first building, four-story Nassau Hall. It was the largest academic building in the Colonies when it opened in 1756.

William Jr. succeeded his father as pastor of the Warwick church. On arriving late for a trustees’ meeting during the early years of the college, he walked in on a discussion of selling it to the state. Tennent couldn’t believe it. “Brethren! Are you mad? I say, brethren, are you mad?” he scolded. “Rather than accept the offer, I would set fire to the College edifice at its four corners, and run away in the light of the flames.”

The chastised board went no further. The college remained a private institution and in 1896 got a new name.

Princeton University.