American chestnuts once reigned supreme over Bucks County and then vanished.

During our California honeymoon, Mary Anne and I drove high into the Sierra Mountains to Calaveras Big Trees State Park near where I grew up. It’s a very unusual place. Mary Anne had never seen anything like it. She’d lived most of her life in Bucks County where trees were of normal height (as Mitt Romney might put it). The Big Trees are the tallest trees in the world. Standing at their base you can barely make out their tops 300 feet above. Their trunks are more than 20 feet wide with a spongy bark that makes them fireproof. Mary Anne and I contemplated the wonder of these 2,000-year-old goliaths while standing on the stump of one of the largest, a Giant Sequoia cut down by early pioneers for a dance platform. Suddenly there was a whistling sound from above. Someone yelled “Watch out!” A 2-foot-long pinecone careened off the stump next to Mary Anne. Close call.

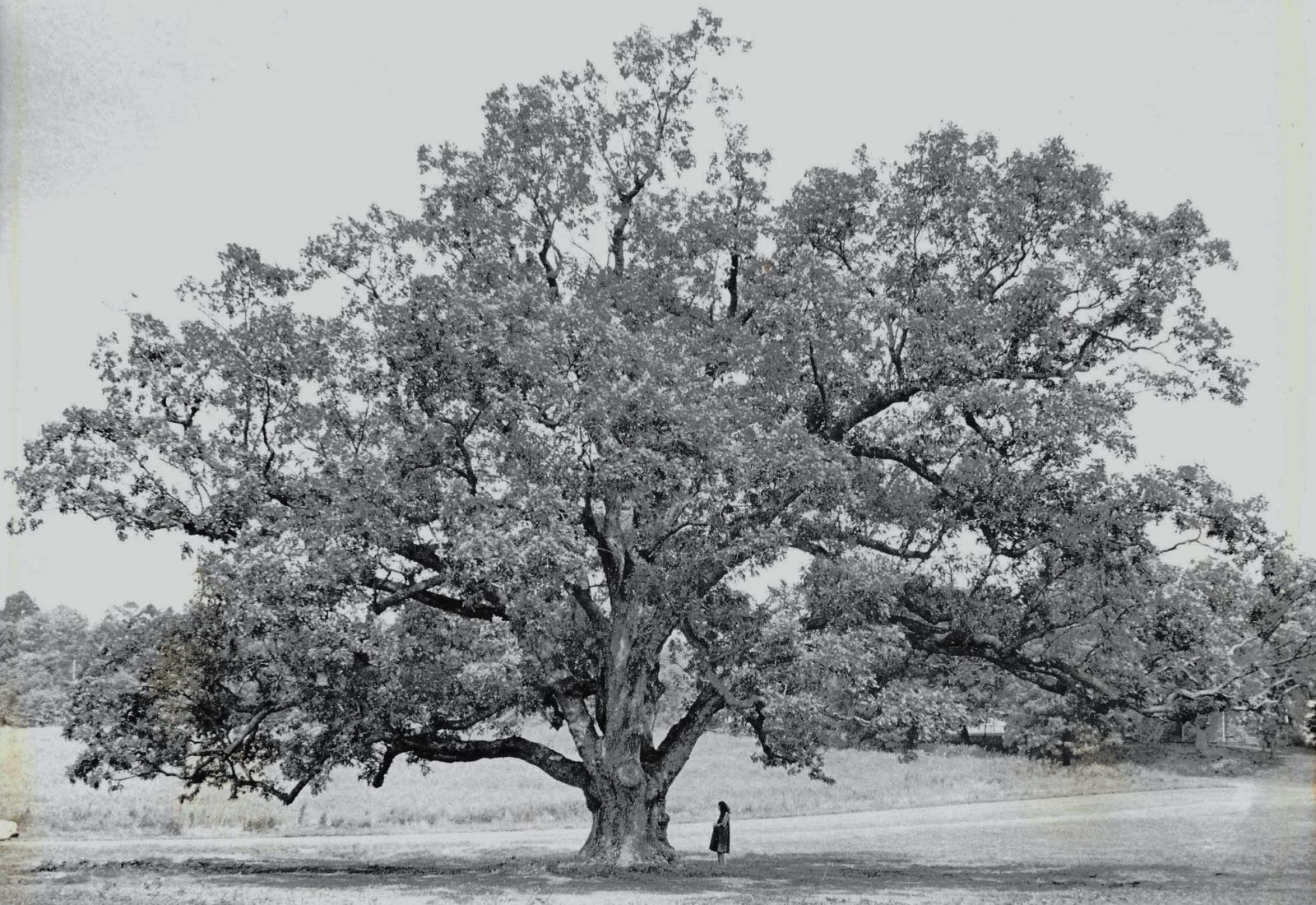

Back home in 1979, the only comparable living tree we could find to vaguely rival a Big Tree was a 500-year-old Solebury white oak, destroyed by a thunderstorm in 1996. For us, it was awesome to stand in the tree’s shade.

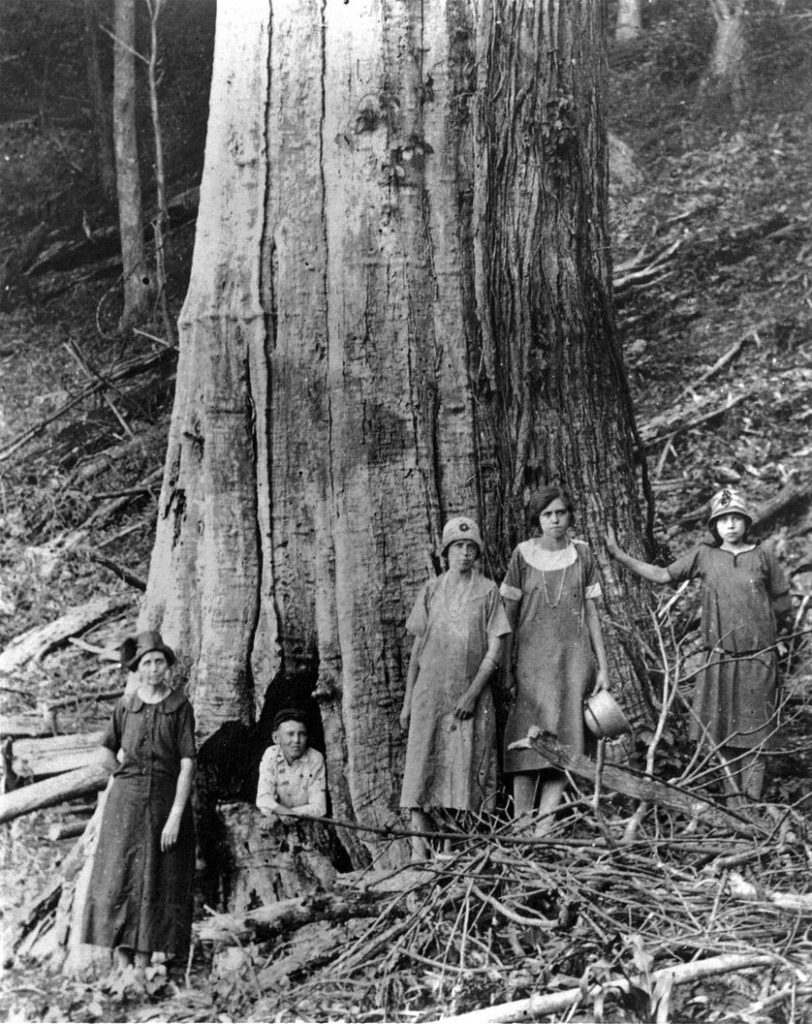

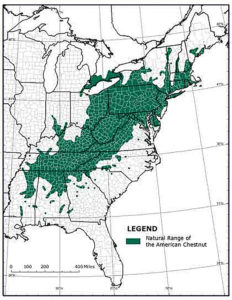

Which brings me to the “Sequoias of the East” – the American chestnut. When the first Europeans arrived, vast forests of them existed from Maine to Georgia, nearly matching the cathedral magnificence of what we saw in California. They were as tall as a 15-story building with massive trunks with a canopy like no other. In clearings, they made ideal shade trees with deep, broad crowns producing sweetly-scented carpets of creamy-yellow blossoms every June and July. In Solebury, an ancient strand on an old Indian trail leading to Aquatong Spring became a well-known romantic setting in Colonial times. Said one pioneer, “It was an ideal ‘Lovers Lane,’ with the big old chestnut trees interlacing their branches over head and the huckleberry and wild honeysuckle bushes covering the ground both sides.” For centuries, settlers made great use of chestnut lumber, rich in rot-resistant tannic acid. Logs were easy to split for cabins, furniture, caskets, posts, railroad ties and split-rail fences. The fall harvest of edible chestnuts produced a major cash crop.

I discovered all of this doing research for my book about the rescue of sailors aboard the sunken submarine Squalus off the coast of New Hampshire in 1939. I made a lasting friendship with survivor Carl Bryson whose South Carolina family earned a living off chestnuts in the 1920s. “I used to go with my grandfather up into the mountains in a wagon pulled by a mule,” he told me. “We’d ring a bell and the mountaineers would come from all over with burlap bags filled with chestnuts. We would pay them one or two pennies a pound and load the wagon right down to the standards. Then we would resell them back home at a profit.”

It was about that time the trees started dying. Not just in the South but up and down the East Coast including here in Bucks County. “It was a horrible thing,” recalled Bryson. “All over the mountains you would see millions of skeletons of the dead trees.

To many scientists, it was the worst ecological disaster in North America since the Ice Age. It began in 1904 when the New York Zoological Garden imported Asian chestnut trees. Soon all American chestnuts in the Bronx Zoo started dying. Specialists identified the culprit: a fungus brought in on the Asian trees. Spores borne by air and rain transmitted the disease. The blight spread north into Connecticut and Massachusetts, and south into New Jersey and Pennsylvania. From there the pestilence made a wildfire advance through the Appalachian mountains and down the coast. All attempts to save the trees – clear cutting, chemical sprays, injection of fungicides – failed. By 1914, the government gave up the fight. Within 40 years, an estimated 4 billion American chestnuts from a species that had survived for 40 million years were dead. Because of the tannin in the wood, the specter of ghost forests stood for another half-century before they too were gone.

Ironically, roots of the magnificent trees remain alive and send up sprouts that flourish until they reach 20 feet, then die off from the fungus. Research continues to clone a blight-resistant American chestnut and headway is being made. Bowman’s Hill Wildlife Preserve in Solebury is helping the effort as a hosting site for the restoration program funded. Several trees recently have been planted. If there is success, it will take hundreds of years before the queen of the forest reigns again. For us, we can only imagine the magnificence of what once existed.

Sources include The American Chestnut Foundation’s website at www.act.org and “American Chestnut” by Judy C. Treadwell published in 1996 and available at

http://www.appalachianwoods.com/american_chestnut_history.htm

Carl LaVO, a retired Courier Times editor, can be reached at [email protected]. Readers might recall his column last year about Sarobia, a mysterious commune that existed in Bensalem. It’s now the subject of a Kindle book ”Sarobia: Sanctuary for Human Beings, Birds and Animals” by Paul Michael Bergeron, available on amazon.com