Historic Fallsington’s Tom Kirkbride revolutionized medicine in the 1800s.

My family might have insisted on medical evaluation had I been acting a little strange in Bucks County in the mid-1800s. Was I was going insane? Fallsington farm boy-turned-physician Tom Kirkbride would have checked off customary known causes. “Excessive lactation?” Nope, hey, I’m a guy. “Religious excitement?” Nope, never been rapturous. “Tobacco use?” Never smoked, sorry. “Metaphysical speculation?” Huh? “Nostalgia?” OK, you kinda got me. “Exposure to the sun’s direct rays?” I did enjoy sunbeams in the Sierra Nevada Mountains on thrice-a-summer vacations as a kid. Check me in, Bro.

Dr. K certainly would have welcomed me with open arms for his specialized insanity cure. The surgeon’s recovery process included leisure reading, playing billiards, physical exercise, farming, planting gardens and strolling their wonders at the doc’s trend-setting Philadelphia hospital. In earlier times, the regimen would have been quite different: shackles, strait jackets and lock-up cells.

The good doctor was born in 1809 to a large farm family in Falls. Young Thomas Story Kirkbride was frail and couldn’t conceive being behind the business end of a mule all day. His Quaker parents understood and envisioned a medical career. That ambition took shape attending schools in Fallsington and Morrisville, “often walking in both directions,” as he later put it. After graduating from high school in Trenton and studying higher mathematics in Burlington City, he entered the University of Pennsylvania medical school and hospital. With his medical degree in hand, he opened a private surgery practice in Philadelphia in 1832. A chance encounter with a pal years later led him to becoming superintendent of a new Penn insane asylum in 1841. At the time, according to the university, people determined to be insane were confined in “the dark, dank basement, chained to the wall and sometimes made to wear ‘madd-shirts,’ which restrained the movement of their arms. For the people of Philadelphia, it was considered a pastime to come to the hospital and peer into the rooms of the insane to witness their episodes. Keepers were given whips and allowed to use them on patients.”

In his residency after graduation, Kirkbride witnessed a more humane approach at a Quaker asylum in Philadelphia. Now at age 31, he brought a similar approach to his new hospital including dropping “asylum” in favor of “hospital” for its name. He removed restraints from patients, letting them move about in the wards. They ate meals in regular dining rooms. None were allowed to sit around idly. Physicians insisted they read, play checkers and billiards, or work the gardens. In Kirkbride’s first annual report he proclaimed the regimen a great success. “From this freedom of action, and from these indulgences, we have found nothing but advantage,” he concluded.

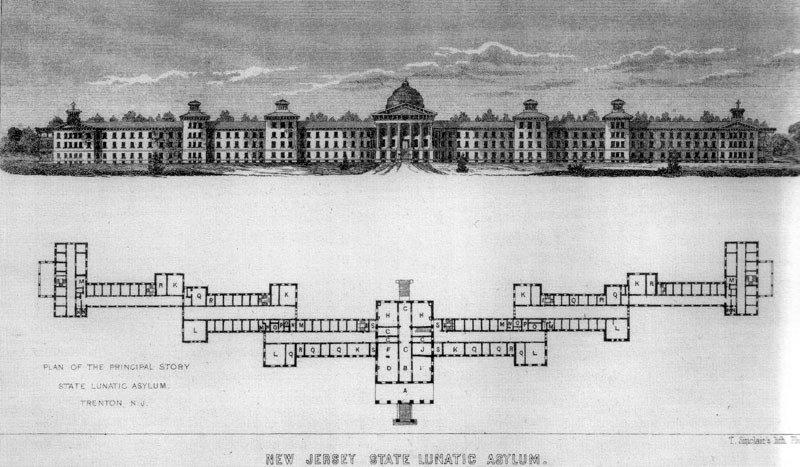

The doctor published his vision of tying hospital architecture to curing insanity. The “Kirkbride Plan” prescribed choosing a site of 100 acres or more at least 2 miles from town. Victorian architecture would inspire awe from the distance. A multi-story central building would adjoin two linear wings containing wards, each wing separated by gender and extending from the central building like a bat in flight. People with manic insanity were confined to the far ends where restraints and morphine could be used if needed.

The grounds would be devoted to landscaping, farming and gardening, enabling patients to work outdoors and enjoy nature. A 10-foot-high wall on the perimeter would provide security but far enough from the hospital to avoid seeming like a prison. Foremost, the hospital would be restricted to no more that 250 patients overseen by 70 employees, equally divided between men and women.

The State of New Jersey was the first to build a Kirkbride hospital in 1848. A decade later, the doctor convinced Penn to build its own. More than 70 others would dot the nation over the next few decades.

Were they successful? Kirkbride estimated 50 percent of his patients at Penn recovered versus a 17 percent rate at conventional asylums. However, the cost of staffing and maintaining such grandeous hospitals at the outset of the 20th Century dampened their appeal. They inevitably became overcrowded and understaffed. By 2001, most had been bulldozed or abandoned to decay like the first on the grounds of the Trenton Psychiatric Hospital across the Delaware River from Lower Makefield.

Dr. Kirkbride’s legacy lives on as a founder of what became the American Psychiatric Association. His compassion for those suffering insanity also remains a guiding principle. When his first wife died of tuberculosis in 1862, Kirkbride married former patient Eliza Butler whom he cured of severe depression when she was a young woman. At the physician’s passing from pneumonia in 1883 at his hospital, she eulogized him. In a letter to an acquaintance, she noted his success stemmed from “sitting down by patients and talking to them in a calm way, which I know from my personal experience, carries help and light to helpless, clouded minds.”

Sources include “Of Beneficent Buildings and Bedside Manners” by Joann Grecco published in the Pennsylvania Gazette on Dec. 17, 2017, and Penn Medicine’s “Dr. Thomas Story Kirkbride” on the web: http://www.uphs.upenn.edu/paharc/timeline/1801/tline14.html