The story of a Bucks tea merchant, a famous poet and a philosopher.

William Ingram of Bucks County made a small fortune operating a tea store in Philadelphia. After the Civil War he purchased 42 acres on County Line Road in West Rockhill where he constructed a beautiful mansion on so-called Ingram’s Mountain.

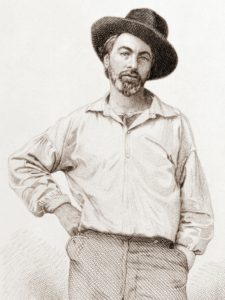

Ingram was a well-educated Quaker humanitarian, drawing him into close friendship with Walt Whitman. The two debated endlessly, Ingram peppering the famous poet with so many questions it sometimes irritated him. As he put it, “He’s a man of the Thomas Paine stripe – full of benevolent impulses, of radicalism, of the desire to alleviate the sufferings of the world – especially the sufferings of prisoners in jails, who are his proteges. He is single-minded-morally of an austere type: not various enough to be interesting – yet always so noble he must be respected. He is a questioner – a fierce interrogator.”

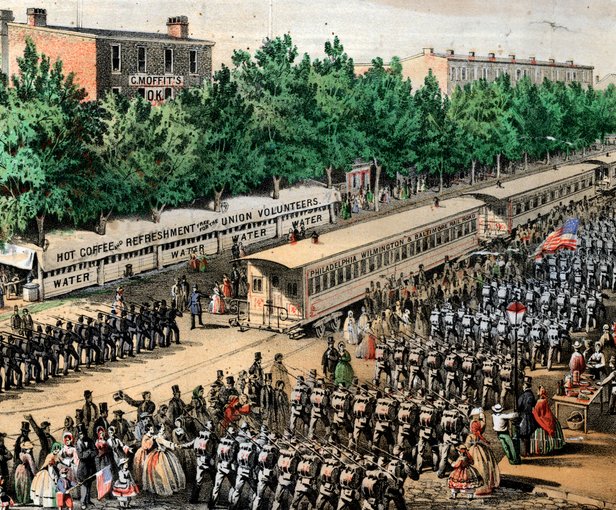

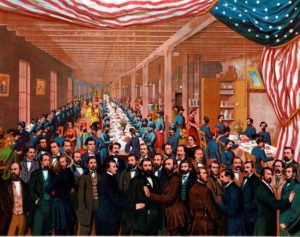

Which brings me to William Cooper, their mutual friend and a noted “free thinker” in literary circles. Cooper’s grasp of world religions was remarkable. But he was best known for his Cooper Shop Volunteer Refreshment Saloon. In 1861, he decided the storefront of his barrel-making factory between the Philadelphia docks and railroad could brighten the spirits of returning Civil War soldiers. The Saloon became a refuge where “the dusty soldier could wash off his travel stains,” as one newspaper put it.

The veterans’ first longing was hot coffee. Cooper obliged by using the plant’s fireplace to brew 100 gallons per hour. He also arranged long dinner tables clad in white linens with white china, dinnerware, mugs, homecoming gifts and floral bouquets. A feast of ham, corned beef, sausage, dried beef and all the trimmings plus desserts honored the soldiers. Cooper became a beloved figure for his largess, serving 600,000 Union soldiers.

The bond between Cooper, Whitman and Ingram remained strong until 1880 when Cooper contracted terminal lung disease. He turned to Ingram to arrange his cremation.

“He wanted me to lay him quietly away with the least trouble and expense possible,” Ingram began in a letter to Whitman. “I made all the arrangements and told him all about it which pleased him very much. He put his arms around my neck in a fatherly way, and said he would now die in peace and thought he would not last till morning, He passed away the next morning without a struggle, his mind was as clear as it was 20 years ago when I first heard him lecturing on Darwin’s theory.”

The next day, Ingram was on hand at the city crematory where his friend’s body was cloaked in a white sheet soaked in alum.

“It was a new experience for me, as I looked through the little glass door and saw my friend vanishing away like a snow flake before my eyes. That thought then as well as now crowded into my brain when I looked on him whom I had known for 20 years, a man that had read all about the Religion and Philosophy of India, China, Egypt, Greece, Rome and Europe and how often we had talked over these people and their Philosophy, and I standing outside that oven was left to think, had his thinking come to an end before my eyes there.

“What a selfish race we are, how we fight with law as well as no law to grasp and accumulate and steal from the poor, all for what? The millionaire, beggar, priest, lawyer, doctor and philosopher all have to come to this as soon as the doctor says that is the last breath he has to breathe and he then can be removed legally into a hot oven and in 2 hours nothing is left of him except 5 lbs of bone dust.”

Ingram reflected on animal bone dust he bought at 2 cents a pound to fertilize his West Rockhill farm.

“So man after all his knowledge and boasting of the millions that he owns is just worth 10 cents,” he concluded in his letter to Whitman. “What a self conceited thing man is, and it was well said of old, Earth to Earth, ashes to ashes, and dust to dust. These are my thoughts as I stood watching for one hour till my friend Cooper vanished away before my eyes.”

That same year Ingram’s daughter Emily graduated from Penn Medical University. Female physicians, however, had a difficult time practicing medicine. So she helped her dad provide care and comfort to inmates in regional prisons. Walt Whitman was so moved he sent a book of poetry to present to an inmate at Bucks County Prison. Ingram wrote back, “I went straight to the prison and gave that book to (George) Rush in his cell with your respects, and how the poor fellow’s eyes shone out with joy for your remembrance of him in prison.”

Sources include “With Walt Whitman in Camden Vol. 1” by biographer Horace Traubel published in 1906; and the West Rockhill Historical Society.