The nation’s most notorious traitor once defended Bucks County in the Revolution.

It seems there’s always a Bucks County connection to just about every event in American history. Billy Penn’s arrival in Falls. George crossing the Delaware in Upper Makefield. Quakertown hiding the Liberty Bell. Ben flying his famous kite in Bensalem. Abe on a whistlestop in Bristol. Neil training to go to the moon in Warminster. And so on.

One little gem that had escaped my attention involves the Logan Inn in New Hope. Benedict Arnold, the Revolutionary War hero-turned-traitor, was posted there to thwart a British invasion in the spring of 1777. On a recent visit to the inn, I remarked in the taproom to a 30-something, “Wow! Imagine that Benedict Arnold drank ale right here.” The response took me by surprise. “Who’s he?”

Let me backtrack. The Logan, the oldest continuously run inn in Bucks County and known for fine dining and overnight lodging, began life as the former Ferry Tavern in 1722. It served travelers crossing the nearby Delaware River on Coryell’s Ferry. With spiced rum in hand at the Logan, Continental soldiers raised a toast to the success of the American Revolution and the downfall of King George III.

Before the war, Arnold was a prosperous Connecticut shipping merchant. When hostilities broke out in Massachusetts in 1775, the 34-year-old militia captain gained notoriety by capturing British Fort Ticonderoga in New York. Subsequently Washington made him brigadier general in the Continental Army. He fought valiantly though seriously injured against superior forces in Quebec and on Lake Champlain in 1776.

By the time Washington crossed the Delaware on Christmas to defeat the British at Trenton, the daring Arnold was a hero. Despite that, the Continental Congress in Philadelphia passed him over to promote five junior officers to major general. Criticism of Arnold by fellow officers as overly ambitious and impatient took its toll. He also won no friends in Congress for constantly seeking repayment for loss of his fortune in support of his troops. John Adams was one of his few defenders. “He has been basely slandered and libeled. The Regulars say he ‘fought like Julius Caesar.’ ”

Arnold eventually became major general though losing seniority to those promoted ahead of him leaving him bitter. But he continued to be a shining star, repelling an enemy attack on Danbury, Conn. in April 1777. That spring, Washington feared British troops from occupied New York would counterattack through Bucks to seize Philadelphia. With the main body of the Continental Army centered around Morristown, N.J., Congress ordered Arnold to secure the western flank of the Delaware including ferry crossings at Bensalem, Bristol, Morrisville, Yardley, Taylorsville (the future Washington Crossing) and New Hope. He established his headquarters at the Logan, a favorite watering hole for Washington who checked in six times during the war years.

Arnold made sure all vessels were removed out of reach of the enemy. From the Logan, he wrote Washington that 4,000 soldiers plus artillery would be sufficient to thwart 20,000 British regulars from crossing over anywhere in Bucks County. “Above Coryells Ferry I am convinced the enemy will never attempt to pass,” he noted.

With the arrival of a brigadier general to take command, Arnold tendered his resignation and left New Hope for Philadelphia to confront Congress about its unpaid debt. Meanwhile, the British Army decided not to swarm Bucks County. Instead, it embarked from New York for the Chesapeake Bay headwaters to attack Philadelphia from the south. Washington scrambled, withdrawing his troops from Morristown to engage the enemy below Philadelphia at Brandywine Creek. Given the emergency, Arnold withdrew his resignation and reported as commander of troops guarding upstate New York where he fought brilliantly in the decisive Battle of Saratoga.

The main army under Washington would lose the Battle of Brandywine. His retreat to Valley Forge enabled 15,000 British soldiers to occupy Philadelphia for 9 months. When they abandoned the city in June 1778, Congress returned and made Arnold military commander of the capital. In the coming months, he ran up lavish personal debt while marrying British loyalist Peggy Shippen.

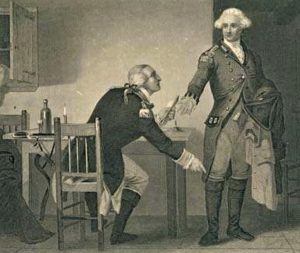

Soured on the Revolution, Arnold began selling military intelligence to British spies and on Aug. 3, 1780 got himself appointed superintendent of West Point, a series of defensive forts on the western side of the Hudson River. Within weeks he offered to surrender West Point to the enemy for 20,000 pounds (worth $4 million today). With the deal tucked into his boot, British Major John Andre was on the way back to New York when arrested. A search revealed the treason and he was hung. Arnold, tipped off, barely escaped on a river boat. Washington sent undercover operatives into New York City to try and nab him. But he slipped away to Virginia, then to London where he died in 1801 at age 60, forever branded a traitor of the American Revolution.

Sources include “My Story: Being the Memoirs of Benedict Arnold” by F. J. Stimson published in 1917; “Colonial Inns and Taverns of Bucks County” by Marie Murphy Duess published in 2007; “Valiant Ambition: George Washington, Benedict Arnold and the Fate of the American Revolution” by Nathaniel Philbrick published in 2016; multiple books on Arnold pulled for me by Katherine Ludwig, curator at the David Library of the American Revolution in Upper Makefield. The Logan Inn’s website is www.loganinn.com.