Bristol Borough had a distinctive French aura as the American Revolution raged in 1776.

Sieur D’Chambeau got a little confused during the early stages of the American Revolution. He was fighting on the wrong side. The French military captain surrendered to American forces while defending a British fort on the frontier near Montreal in 1775. George Washington’s intercession a year later freed him from imprisonment – if you can call it that – in Bristol Borough. The captain had been among 20 French “officers and gentlemen” held as POWs in Bristol. They gave the tiny, mostly Quaker borough a decidedly French flavor. More on that later.

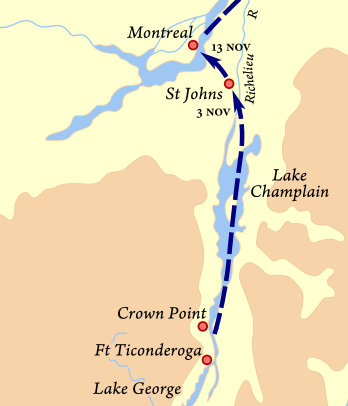

The tale of Sieur D’Chambeau traces back to April 1775 after the Continental Army captured strategic British Fort Ticonderoga in upstate New York. Next aim was Fort Saint-Jean on the Richelieu River at the northern end of Lake Champlain. The fort guarded Montreal 30 miles away. The ultimate plan was to seize the fort, Montreal and Quebec City, then add all of Quebec to the fledgling United States as the 14th state.

The American offensive to take the fort began in September with an army of 1,500 militiamen under the leadership of Gen. Richard Montgomery. After initial bombardment, Montgomery decided to starve the defenders into submission. The siege began on Sept. 18 and lasted 45 days. With the surrender on Nov. 3, 400 British and150 French prisoners were dispersed to stockades and villages throughout New York and Pennsylvania. D’Chambeau and 19 French prisoners – considered the upper crust of Montreal society – began a 217-mile, deep-freeze journey by horse-drawn sleighs from Albany, N.Y. through Easton to Bristol. Borough residents offered them hospitality and housing. They were free to roam town and surrounding areas as parolees. Local historian Burnett Landreth in 1938 commented dryly, “The town of Bristol, a village of 50 dwellings, had a resident population of less than 300. Consequently the billeting here of a body of Frenchmen equal to one-fifteenth of the population of the town, was a marked event, and if they were representative of their vivacious nation, they must have made it interesting for the demure Quaker girls of the village and countryside.”

Though small, Bristol was a popular layover on the stagecoach route linking New York with Philadelphia. The Bath mineral springs in the borough drew many patrons, and the town’s King George II inn established in 1681 was considered the best hotel between the two cities. Owner Charles Bonnett, a native of France, had expanded the inn to its present day form before the prisoners arrived. Enjoying ale with Mr. Bonnett in the inn’s tavern made life more than tolerable for the Frenchmen.

During his confinement, Captain D’Chambeau caught a break. The governor of the French West Indies island of Saint-Domingue appealed to George Washington to free him. “Excellency,” Compte D’Emery began in an Aug. 4 letter, “I hope you will be good enough to release a French Officer, who like an inconsiderate Man, was taken in Canada . . . He is called the Sieur D’Chambeau and is an Officer in a Regiment of Infantry in the Service of his Crown. Altho’ this Officer has fallen into an Error, by taking part in a Quarrel, in which he ought by all Means to have been a Neuter, either considered as an Officer of France or a Canadian, I could not, seeing he had wrote to me, refuse to use my Interest with your Excellency, to suffer him, by an Act of Generosity, to regain his Liberty and join his Regiment in Europe.”

Washington received the letter in early October and agreed. “I take the earliest Opportunity of testifying the pleasure I have in complying with your request, by immediately ordering the Release of Monsr. Dechambault. He shall be accommodated with a Passage in the first Vessel that sails from Philadelphia to the French Colonies in the West Indies. . . . I could not hesitate to comply with a Request made by a Nobleman who by his public Countenance of our Cause has rendered such essential Services to the thirteen united independent States of America, whose Armies I have the honor to command.”

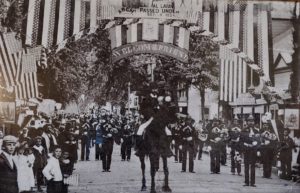

As D’Chambeau sailed away, his fellow Frenchmen remained in Bristol a bit longer. Washington, meanwhile, prepared to make his celebrated Christmas crossing of the Delaware in Upper Makefield to attack Trenton. France had aligned itself with the American cause, generating more warm feelings in Bristol. A year later French Marquis De Lafayette would be treated overnight in Bristol for his wounds on the Brandywine battlefield. By then Bristol had learned a little French and on Lafayette’s departure, “Viva La France” echoed in the streets as he left for Langhorne and eventual recovery at a hospital in Bethlehem. Lafayette would return to Bristol as a guest 48 years later in an emotional farewell tour.

Sources include “A History of Bristol Borough” by Doron Green published in 1911, and correspondence between George Washington and French West Indies Governor D’Emery found on the Internet at founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-05-02-0423