The 1920s will be reborn in October to mark 90th anniversary of New Hope’s iconic art haven.

My late grandmother as a young woman would have loved a special event scheduled for October in New Hope. Ivy Lavon would have cut the rug in a dazzling Charleston dance move that would fit right in with “A Roaring ’20s Soiree” to mark the 90th anniversary of the Phillips’ Mill Community Association.

The grist mill and its village have long defined the fine arts tradition of New Hope. It was there in the early 20th Century that William Lathrop became the Aristotle of the Pennsylvania Impressionist movement, teaching the technique to understudies who made Phillips’ Mill famous. On Oct. 26, members will look back on all 90 years by reincarnating the “Roaring Twenties” era when Lathrop’s art movement gained traction internationally. The soiree will feature guests arriving in period dress at Hotel du Village near the mill to enjoy live music, dinner, dancing and a “Speak Easy” review. Earlier in the day, they will view the prestigious Fall Art Exhibition at the old mill.

About 20 years before George Washington made his famed crossing of the Delaware River just downstream from New Hope, William Kitchen built the grist mill on Primrose Creek on the upstream edge of the borough in 1743. He sold it and 100 acres to his half brother Aaron Phillips. Three generations of his family ran the mill until 1889 when Charlie Phillips sold it, the adjacent miller’s house and village on 27 acres to Stephen Betts and his wife. The couple supplemented their income by renting the house as summer quarters to Philadelphia physician George Morley Marshall and his family. They were so taken by the beauty of the property and surrounding area that the doctor purchased the site in 1896 from the Betts family including their nearby home which they made their own.

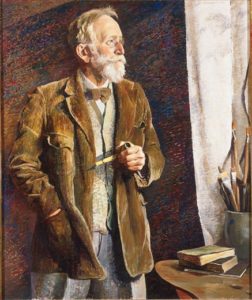

Enter New York City artist Lathrop. Both he and Marshall grew up childhood pals in Painesville, Ohio. The physician believed Phillips’ Mill, its village and the pastoral surroundings would captivate Lathrop. It did. A couple years later, the doctor sold 4 acres including the miller’s house to the artist and his family. Marshall retained ownership of the mill which became a playhouse for children of both families.

Lathrop convinced his friend Morgan Colt to relocate to the mill village in 1903. Colt was a frustrated architect who had many artistic interests including woodworking, sculpture. wrought iron and leather. He remodeled the mill’s piggery into a home and built a studio. He incorporated a Gothic/Tudor design reminiscent of an old English village including elaborate walled garden that stands today on River Road across from the mill.

Meanwhile, Lathrop established a school for budding artists. His habit was to greet students at the train station in New Hope, then have them board a 12-seat motor boat named Sunshine. He’d helm the put-put north from the train station on the Delaware Canal a few miles to Phillips’ Mill. On the way he had passengers sketch the passing countryside in the “plein air” style Lathrop had perfected. As many as 15 students at a time would set up easels on the edge of the canal near the mill and take instruction from the master painter. On Sundays, his effervescent wife Annie hosted afternoon garden parties behind the couple’s home. The Lathrops also turned outbuildings into cottages for a colony of visiting artists. The village became a gathering place for up-and-coming artists, writers and actors. Annie set everything in motion. “There were dances, refreshments, cake and ice cream . . . it was real without radios,” recalled Newlin Price, a New York gallery owner and tea party regular.

By 1916, six artists – Lathrop, Colt, Daniel Garber, Charles Rosen, Rae Bredin and Robert Spencer – were exhibiting their works nationally as the “New Hope Group”. Eventually they and others like Fern Coppedge, John Folinsbee, Edward Redfield and Walter Schofield became the Pennsylvania Impressionists of the New Hope Art Colony, cementing the borough’s fame internationally.

In 1929, aging George Marshall hoped to perpetuate the grist mill as a community arts center. Out of that concern the Phillips’ Mill Community Association was born that yea, took possession and hosted its first art exhibition. Lathrop continued producing art and teaching students for more than 30 years at Phillips Mill.

Since its foundation, the association has remained independent, annually hosting prestigious art and photo exhibitions, forums and dramatic plays separately for adults and children. Across from the mill, Brooks and Joyce Kaufman in 1972 transformed the teahouse into The Inn at Phillips Mill. It remains an indoor/outdoor destination for French country dining by candlelight where aficionados like me soak up the legacy of the physician, the painter and his colony of artists who immortalized the Bucks County landscape.

Sources for this column include “Pennsylvania Impressionism” edited by Brian H. Peterson and published by the James A. Michener Art Museum; and “Phillips Mill Historic District” at www.livingplaces.com.