Warminster man who invented the steamboat in Bucks County had a tragic end.

Folks here have long lionized one man’s impact on 19th century America. He invented the steamboat in Bucks County. Perhaps a lack of business acumen and human touch prevented him from realizing the riches and acclaim that others would make off his invention. It was not for lack of trying however. He ended life as a disheveled recluse called “Crazy Fitch” and was buried in an unmarked grave far from home.

So who was John Fitch?

Born into a Connecticut farm family in 1743, he loathed fieldwork to the resentment of his father and brothers. Tall and slim with black hair and penetrating eyes, young Fitch preferred books. He devoured mathematics, astronomy and geography. Temperamental and extremely unhappy at home, he learned the rudiments of brass-making and opened a metal-working shop in his mid-20s. The business died due to mounting debt. Permanently abandoning his wife and two children, Fitch roamed aimlessly until finding employment as a silversmith in Trenton, N.J. He became good at it while repairing and refitting arms for George Washington’s rebel army. When the British occupied Trenton in November 1776, he fled to Warminster where he made silver buckles, buttons, spoons and mugs, and also sold tobacco and beer to the Continental Army at Valley Forge in 1777.

Fitch invested his savings in undeveloped land in Virginia, Kentucky and Ohio where he endured a year of captivity by Native Americans. Back home and suffering from rheumatism, Fitch was struggling along Street Road when a horse-drawn chaise passed. In a flash, he conceived the idea of a steam-powered rolling chair. Realizing roads were too rough to make that successful, he turned to pioneering a model boat with stern-mounted paddles on a crank shaft attached to a steam engine he built. Encouraged by a successful trial on an Upper Southampton pond, he went to work building a full-scale version in a Philadelphia shipyard.

Fitch needed money. But appeals to Congress, Ben Franklin, George Washington, James Madison and Patrick Henry proved fruitless. Nevertheless Fitch cobbled together enough cash from private stock offerings in 1787 to launch the world’s first steamboat. The following year he made history steaming up the Delaware to Burlington, a distance of 20 miles. “We reigned Lord High Admirals of the Delaware,” he boasted. Later that year, he carried 30 passengers on a round trip and inaugurated service between Philadelphia and Trenton. Though slow moving compared to speedy stagecoaches, Fitch lured passengers with free beer, rum and sausage. He lost money on every voyage.

Though Congress issued him a patent in 1791, Fitch was unable to attract major investors to expand business to the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. Frustrated, he left for France where he marketed his steamboat design and a prototype of his successful submarine to both France and England. Again he failed. In Paris, he left his steamboat master plans in the care of an associate who loaned them for several months to visiting New York inventor Robert Fulton.

Fitch returned from Paris in a funk. He retired to Kentucky where he discovered that 1,300 acres he owned around Bardstown were occupied by squatters who had established thriving plantations. Fitch sued. He got nowhere. As he lingered in town, one resident described him as “dignified, distant, and imposing. He appeared on the streets in black coat, a beaver hat, a black vest, with light-colored short breeches, stockings, large shoe buckles and coarse shoes; the representative of another age and school of life. Among the hunting shirts of Kentucky, such a style of dress and intercourse attracted observation.”

Fitch’s disillusionment grew. “The day will come when some more powerful man will get fame and riches from my invention. . . . vessels propelled by steam will cross the ocean. And I almost venture to prophesy that the same power will be utilized in moving vehicles on land.”

Poor Fitch’s appearance became shabby with a face that twitched nervously. Children called him “Crazy Fitch.” Broken in spirit and unable to sleep, he drank heavily and slipped into eternity at age 55. His landlord found the body on July 2, 1798 with burial in an unmarked pauper’s grave. Nine years later on the Hudson River, Robert Fulton launched the Cleremont based on Fitch’s work. Fulton’s paddle-wheel steamboats soon became ubiquitous on America’s rivers. He became rich and famous. Steam locomotive trains that Fitch envisioned soon would span the nation.

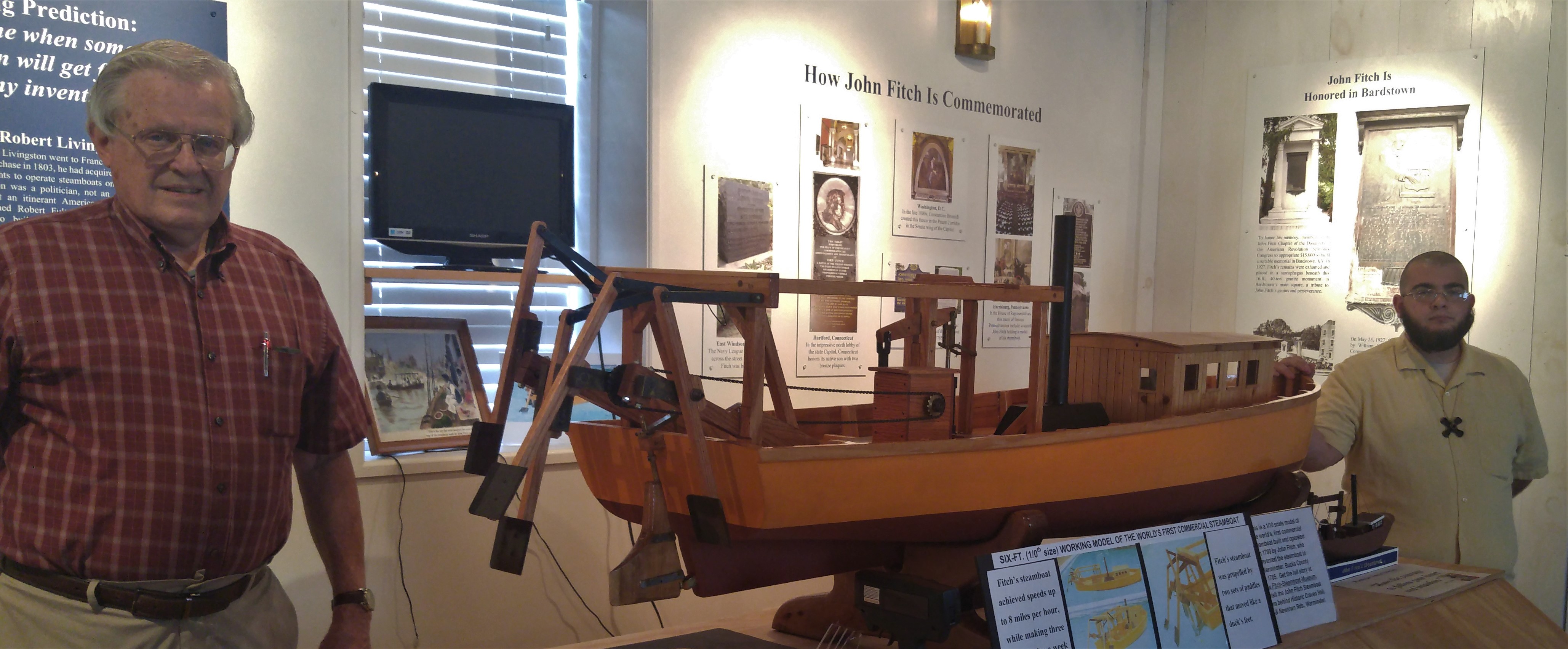

It would take a century before “Crazy Fitch” was rediscovered. In 1908, the Daughters of the American Revolution located his grave and placed a simple marker there. Eighteen years later, Bardstown citizens dedicated a monument to him. Back in Bucks where his dream became reality, a unique museum in Warminster tells his story. There you can witness a working model of his miraculous steamboat that revolutionized the world.

Sources include “Justice to the Memory of John Fitch” by Charles Whittlesey published in 1845; “Steam: The Untold Story of America’s First Great Invention” by Andrea Sutcliffe published in 2004; and the John Fitch Steamboat Museum located at the corner of Newtown and Street Roads, Warminster. Information about the museum is on its website, www.craven-hall.org or by calling 215-675-4698.

Carl LaVO, a retired Courier Times editor, can be reached at carllavo@msn.com. His new coffee table book“Bucks County Adventures” is available at the Newtown Bookshop, Doylestown Bookshop or can be ordered online at his website, www.buckscountyadventures.org