Morrisville and Buckingham share a linkage.

I’ve always admired surveyors and the precise way they go about topography using specialized instruments. But an Arnold chronometer and a sextant like that used by a Buckingham native to lay out Washington, D.C. are of no use 110-feet below the surface in one of Florida’s subterranean rivers. For me in my pioneering days of spring diving in the 1960s, spooled nylon lines of measured length were necessary in charting the water-filled labyrinth of Peacock Slough. Using nickle cadmium-powered aircraft landing lights to illuminate the darkness, additional air tanks, decompression and depth gauges and other high-tech instruments, we members of the University of Florida Speleological Society were the first to begin the delicate task of charting interconnected springs in the slough. Today the cave network is the largest mapped underwater cave system in the world and still growing.

My interest in map-making from back then brings me to the story of how the nation’s capital came to be. It was supposed to be Morrisville. That was the intention of Robert Morris, a Philadelphia banker who lived in the borough named for him. He’s perhaps best known for financing the American Revolution. Congress in 1783 had agreed to build the capital in his hometown on the high ground near his Summerseat mansion. Before survey work could get underway, Southerners convinced Congress to build the capital nearer the Mason-Dixon Line. In 1790, Congress gave George Washington authority to chose a 10-square-mile site for the capital along the Potomac River.

Though no capitol dome rose in Morrisville, the birth of Washington, D.C. would have another Bucks linkage – Buckingham and its famous surveyor Andrew Ellicott.

Andy was born in1754 in the township. He and his eight siblings worshiped and were schooled at the Buckingham Friends Meeting. Little Andy demonstrated a gift for mathematics, interest in astronomy and mechanical ability.

At age 16 before marriage to wife Sarah Brown of Newtown, he moved to Maryland where his father and uncles founded a grain mill in the future Ellicott City in 1775.

During the American Revolution, Andy was a major in the Maryland militia. After the war, he headed a survey team to establish the Mason-Dixon Line, today’s border between Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland. He also charted the east-west border between Pennsylvania and Ohio, and made the first topographical survey of Niagra Falls to assess its height and breadth.

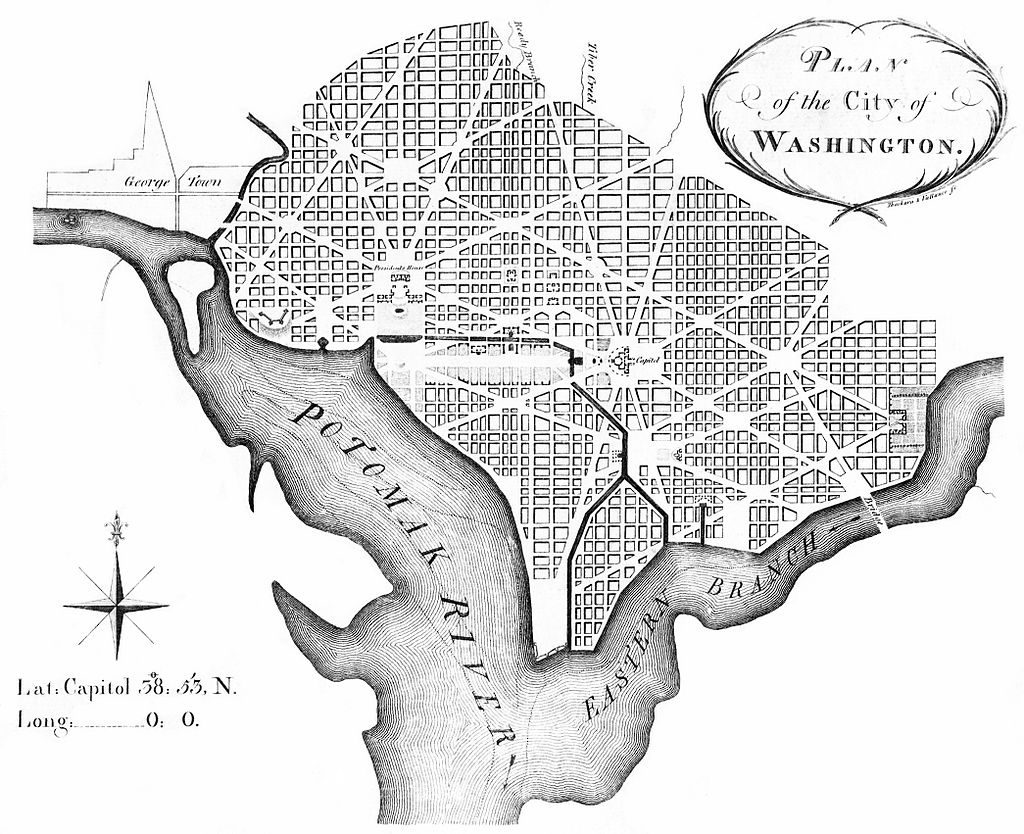

Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson was so impressed he chose Ellicott in 1791 to establish the border of the new 100-square-mile District of Columbia. Over a two-year period Ellicott and his team set out boundary stones, each separated by one mile. Most are still in place, etched by Ellicott. He also accomplished the first survey for the future city of Washington. But it was Pierre Charles L’Enfant who prepared the street plan. When Pierre failed to deliver an official map, Andy inherited the project. He made various revisions like straightening Massachusetts Avenue and the boundary of Judiciary Square. The final Ellicott plan was printed in 1792 and widely distributed.

Two years later, Ellicott planned the city of Erie as a future port on the Great Lakes. President Washington also commissioned him for a four-year survey of the border between Alabama, Georgia and Spain’s territory of Florida.

Souring on federal service after the Adams Administration refused to pay him, Ellicott retired to Lancaster, Pa. There in 1803, President Jefferson approached him for a favor. Could he teach his surveying techniques to Meriwether Lewis? Andy jumped right in, inviting Meriwether to his home where he lived for two months learning Ellicott’s method of using sextants, Arnold chronometers, surveyor compasses, plotting instruments and artificial horizon tools needed for accurate topographical maps. Ellicott also recommended the equipment needed for Meriwether’s ultra secret mission – the Lewis and Clark Expedition to map a course across the unknown American West to the Pacific Ocean.

After his long hiatus at home, Ellicott helped settle a border dispute between North Carolina and Georgia. He later moved to New York where he became math professor at the U.S. Military Academy in West Point until his death seven years later at 66.

Ellicott never lost appreciation of the wilderness. It comes clear in a letter to President Jefferson on June 3,1812 from the North Carolina/Georgia borderlands where he witnessed the Great Comet. “During this excursion I have made a considerable number of astronomical observations, exclusive of those used for the determination of the boundary, particularly on the eclipse of the sun on the 17th of September last, and on the comet, which I shall forward to the National Institute,” he wrote. “Our operations were performed in a very interesting part of the country, on account of the numerous mountains, stupendous precipices of granite rocks, and beautiful cascades.”

Sources include “Washington: A History of Our National City” by Tom Lewis; “Andrew Ellicott: The Stargazer Who Defined America” by William J. Morton; “Discovering Lewis & Clark” at http://www.lewis-clark.org/article/2338; “Andrew Ellicott to Thomas Jefferson, 3 June 1812″ at Founders Online, www.founders.archives.gov