The Upper Bucks town was once baseball capital of the Major Leagues.

I know, I know. There’s Cooperstown. I’ve been there to see a friend enshrined in the Hall of Fame. But, but, but . . . There is another special town in Major League Baseball history. It’s here in Bucks County. Perkasie.

For nearly two decades the little town stitched together every single hardball in play at professional ballparks throughout the United States. Babe Ruth hit Perkasie balls to establish a record 714 home runs in 1935. Joe DiMaggio of the New York Yankees hit them safely in 56 consecutive games in 1941, considered the most unreachable record of all-time. Hal Newhouser of the Detroit Tigers twirled them in the 1944 and 1945 as the only pitcher to win back-to-back MVP awards. Perkasie hardballs also were in use when Philadelphia Athletics manager Connie Mack was setting the all-time record for most wins by a Major League manager.

So how did Perkasie achieve such lofty status?

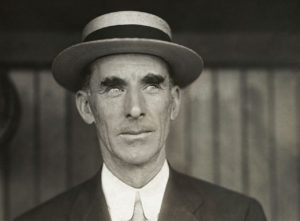

Enter brothers Walt and Ed Hubbert. The two young men had been employed in Philadelphia after World War I stitching balls for the growing sport of baseball. After marrying two sisters, they hatched a great idea for raising their families and stitching baseballs: Move to Perkasie, population 2,779.

Perkasie is a Native American term, the meaning of which is endlessly debated. Some insist “area teaming with mice”. Others, “a place of peaches.” Ultimately, a single translation was agreed upon between Bucks historian George MacReynolds and state government: “The place you go to crack hickory nuts.” That fits. Hickory nuts and Hubbert baseballs are super hard and capable of long-distance flight. Beyond that, Perkasie gained notoriety for hosting the powerful Athletics in an exhibition game against the town’s amateur team in Menlo Park in 1909. The A’s won by a 16-3 score and went on to capture Philadelphia’s first World Series pennant the following year. One newspaper reporter commented after the error-filled Perkasie game, “It was evident the local players had a bad case of stage fright.”

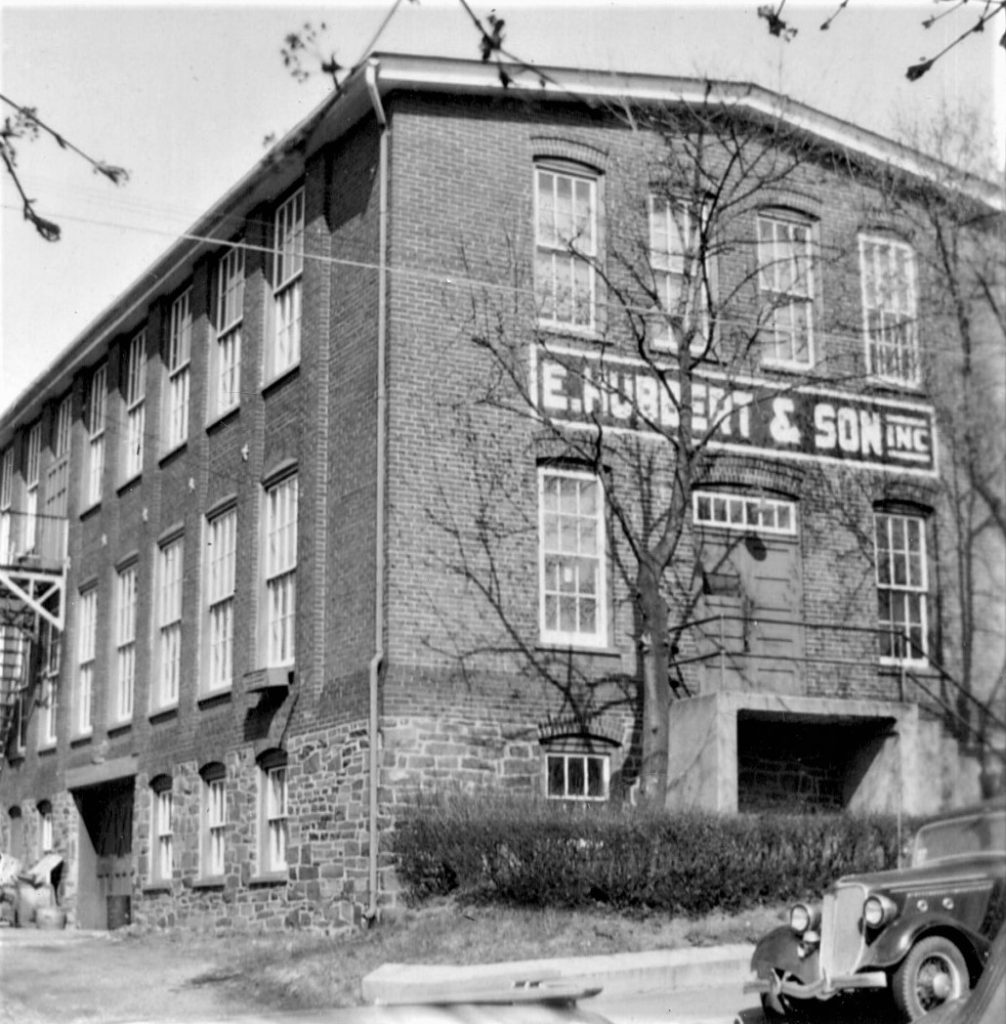

In 1920, the Hubberts started stitching baseballs in their Perkasie kitchens with family members and local residents. They cut tanned horsehide from France into covers and double stitched them in red thread around centers made from Portugese cork overlain by two layers of black and red rubber from Malaysia, then tightly wrapped in Australian woolen yarn. The Hubbert ball was lively in contrast to baseball’s earlier “dead ball” era. Despite critics charging the balls were “juiced”, A.G. Spalding Co. signed E. Hubbert & Son to a 15-year contract in 1935 to produce all balls used by the American and National leagues. The family soon employed 50 stitchers at a two-story factory on Chestnut Street and about 300 others in their homes.

At its peak, the Hubberts employed a third of Perkasie’s population. Over time, 2,000 borough residents were trained to stitch baseballs. All sports records set in both leagues between 1935 and 1950 involved balls coming out of Perkasie. It was in the mid-1930s, stitcher Harvey Freed and his Perkasie pals drove a Model A Ford to Shibe Park in Philadelphia to take in an A’s game. Sitting in the centerfield bleachers, Freed caught the only home run in the ninth inning. It was a blast by the great first baseman Jimmy Foxx of Doylestown. Later, Freed’s friends urged him to unstitch the ball to reveal who sewed it since every one contained the stitcher’s initials. It turned out to be Freed’s. As David Hubbert recalled, Freed “carefully re-stitched the ball, which became the prize of his life. It was proudly displayed on his living room mantel until the day he went to baseball heaven.”

All good things come to an end, of course. In 1950, the Spalding contract expired, putting the Hubberts out of business. That’s when the inventive family came up with another idea. Walt’s son David developed a much improved, very durable softball that revolutionized the sport. His enterprise began in the basement of his Perkasie home, then quickly expanded through the Dudley Sports Company in New York. Sales soared. Production of 6 million softballs a year ensured employment of 1,000 stitchers in the Perkasie area. An old fire house and a 60,000-square-foot former pants factory behind today’s Dairy Queen in Dublin handled production. So did buildings in Sellersville.

By the 1990s, outsourcing to Georgia and Haiti brought the Perkasie tradition to an end. All that’s left now are the memories. “I feel that stitching baseballs was a source of pride for the Perkasie community,” Rick Doll of the Perkasie Historical Society told me recently. “Knowing that every baseball used in America’s Pastime was stitched here was and is something to be proud of. Everyone in town at one time either stitched baseballs or knew someone who did.”

Sources include “Place Names in Bucks County Pennsylvania” by George MacReynolds published in 1942; the Perkasie Historical Society Museum; and“Preserving Perkasie: A local history resource” found on the web at https://preservingperkasie.com/ . Information about the museum can be found on the web at http://perkasiehistory.org/.