Memorial held for Quaker slaves buried at meetinghouse

They were slaves owned by Quakers. They were fugitives. They were free men and women. Their lives passed and then they were buried in unmarked graves. Forgotten. For some the passage of time has been 325 years. On Oct. 6 in Langhorne, the memory of the faceless will be resurrected at the Middletown Friends Meetinghouse on West Maple Avenue. An anticipated crowd of 400 will assemble to memorialize enslaved and free people of African descent buried on the meetinghouse grounds. The Lincoln University Concert Choir, renowned vocalist Keith Spencer, violinist Claudia Pellegrini and historian Jesse Crooks of Doylestown will help dedicate and consecrate the hollowed ground.

In Colonial times in places like Philadelphia, cemeteries set aside for deceased slaves were gathering places for the black community to speak and sing in their native tongues and celebrate deliverance in African dances. In Bucks, that was not allowed, in part due to the small number of slaves. The only interaction allowed was at twice-a-year street fairs in Bristol where they could intermingle, but only on the last day.

You have to reach back to 1673 when local Quakers founded the Middletown Monthly Meeting of Friends to understand their burial practices. Many owned slaves. Typically in Bucks, slave owners buried the deceased in unmarked graves in farm orchards or woodlands. Middletown Friends, however, allowed members to bury their slaves within the meetinghouse’s common cemetery beginning in 1693. Ten years later the practice was abruptly halted after some objected to both races within the cemetery. The burial ground became segregated behind a stone wall.

The importation of slaves into Southeastern Pennsylvania continued to climb. By 1751, an estimated 11,000 served as farmhands or domestic servants, 6,000 in Philadelphia.

After the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting of Friends banned slave ownership in 1776, Middletown Friends decided its members must free their slaves or be ousted. The meeting began an outreach to the free African American community, inviting them to worship. The Friends also purchased a small plot of land in front of the meetinghouse to create a “Negro burying ground”. The graves remained unmarked and unrecorded in accordance with Quaker tradition at that time. Only one documented burial occurred there in 1812 – that of Cato Adams, a free black who lived in Middletown and later moved to Bristol. He bequeathed money to perpetuate the care of the cemetery.

When the site reached capacity in 1816, Anne Twining of Middletown Friends donated additional acreage on nearby Green Street as a new burial ground for free blacks. The two black cemeteries remained the only ones in Bucks County for African Americans until 1809. That year Langhorne’s newly-built Bethlehem African Methodist Episcopal Church on Route 413 reserved a portion of its property as a burial ground. Sixty years later, the church purchased the Green Street graveyard from Middletown Friends and named it Mt. Olive.

Holly Olson, coordinator of Saturday’s event and member of the meeting, initiated the memorial drive nearly two years ago when she was stunned to learn slaves owned by Quakers were buried in unmarked graves near the meetinghouse. Determined to atone for what happened, she put together a committee that included Langhorne’s African American Museum of Bucks County. “We reached out to the museum right from the start,” said Olson. The museum’s Roger Brown and Gerlyn Williford joined the effort as well as Brenda Cowan, a leader of Langhorne’s black community. Others included members of the Yardley and Middletown Friends Meetings, and Sacred Heart Catholic Church of Camden, N.J.

Saturday’s ceremony will include dedication of bronze plaques affixed to two large boulders, one at the entrance to the original Quaker burial ground and the other next to the burial ground where Cato Adams lies. Each memorial tablet reads, “This plaque is in remembrance of the forgotten slaves who were owned by members of Middletown Monthly Meeting.”

Etched on one of the stone tablets is this poem by Brenda Cowan:

I’ve come to the end of the road/My days of living in bondage is done./The sun has set for me./Yes, I’ve crossed over to glory./Why cry for a soul that is finally, finally free.

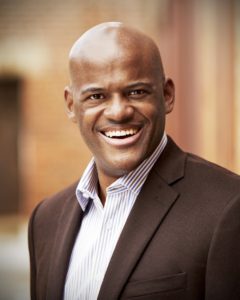

Keith Spencer, a nationally-known baritone and actor who has performed at the Bristol Riverside Theater and many other venues, put Saturday’s event into perspective for me.

“What I find most compelling is that in a time when our country is rife with divisive rhetoric, this event is not one about reparations and pointing blame. Instead we have a multi-cultural community coming together simply to ‘make things right’ regardless of the reasons or ways of the past. This is about the simple restitution of honor and dignity due our fellow man. What better reason to come together and show support? I know it will be a truly moving event.”

Sources include “The Negro in Pennsylvania: Slavery-Servitude-Freedom 1639-1861″ by University of Michigan history professor E. R. Turner published in 1911, and “The forgotten ‘Negro burying ground’ at Middletown Friends Meeting” by Jesse Crooks available on his website, www.burnbridle.com