A look back at bringing culprits to justice in 19th century Bucks County.

There was no messing around when it came to law and order in Bucks County’s early history. One look at John Hough in 1786 told you that. Poor John stood before Judge Henry Wynkoop to be sentenced for horse thievery. Justice was swift. Hough was fined 40 English pounds (equivalent to $6,720 today). He had to stand for one hour in public disgrace in the pillory in downtown Newtown where he received 39 lashes. Following that he went to prison for six months. Even worse he had his ears cut off!

Sentences for stealing a horse could stretch a lifetime with no probation for good behavior. In rare cases, defendants were hung. After all, being left afoot in the wilderness by a horse thief could prove fatal for settlers of that period.

Horse thievery wasn’t the only crime citizens in Colonial Bucks had to deal with. Theft of farm equipment, holdups and vandalism were among villainous behavior at a time when law enforcement stretched thinly across the county. By the 1800s, a 400 percent increase in burglary and larceny moved citizens to organize call networks to foil criminals. In 1819, the Newtown Reliance Company for the Detection and Apprehension of Horse Thieves and Other Villains began operations. By 1855 others took shape in Buckingham, Solebury, Washington Crossing, Warminster, Perkasie, Yardley, Bristol Township and 33 other Bucks locales. Members became vigilantes on horseback investigating crimes and apprehending criminals. The companies also insured members from loss by collecting membership dues.

I recently met Kimberly Yocum to get a handle on all this. We met at the Village Library in Penns Park in rural Wrightstown where you easily can imagine tying up your horse outside. Kim was overflowing with historical documents from her membership in the Franklin Company for the Purpose of More Effectually Detecting Horse Thieves & Other Villains based in Furlong and founded in 1865.

As she explained, “horse companies” were insurance partnerships dedicated to thwarting thieves. Valuable horses could easily be ridden out of county for sale elsewhere for big bucks. “If someone came and reported ‘My horse was stolen’, the Telegraph Committee issued a call to ride,” explained Kim. This meant ride like the wind. Fast.

Here’s how it worked:

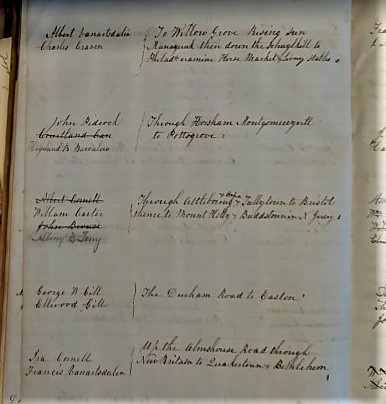

At the company’s annual meeting, usually in January, members would pay their dues and choose routes and riders to cover the territory in league with other companies. At inception the Franklin Company took responsibility for routes radiating from “telegraph committee” headquarters in Lambertville and Doylestown. Fred Anderson and Jonas Fretz were assigned Route 4 (New Hope to Pennington, N.J.). Josiah and Seneca Hellyer got Route 5 (New Hope to Mount Holly, N.J.). Ephraim Slack and Robert Heston drew Route 7 (Lahaska to Mount Holly). Samuel Doughty and Henry Carver, Route 13 (Buckingham to Philadelphia). Route 24 went to Gibson Johnson and Albert Paist (Dublin to Lehigh Water Gap). James Shaw and lawyer N. B. Heacock got Route 34 with orders to “examine stables and farms” on roadways leading to New Brunswick, N.J.

The company employed five bounty hunters and posted $100 rewards (about $1,500 today) “for the arrest and conviction of a horse thief or other villain.” In covering losses, Franklin valued Alfred Ely’s missing horse at $80 ($1,200) and paid him $60 ($900). When thieves burgled John Umstat of Carversville, he submitted a claim for stolen wheat, corn, lard, 12 cans of fruit and 2 grain bags. He received $11.90 ($290 today).

The nation’s first horse company came about in 1810 in Dedham, Mass. “It is evident that there has been, and probably will continue, a combination of Villains through the northern states to carry into effect the malignant design, and their frequent escape from the hand of justice stimulates them to that atrocious practice,” the Society for Apprehending Horse Thieves warned. “(Thievery) requires the utmost exertion of every good member of society, to baffle and suppress depredations of this kind.”

Tracking down villains often failed though property was recovered.

In 1909 a horse named “Old Blackie” disappeared under suspicious circumstances from a horse shed in Red Hook, N.Y. The alarm sent riders racing in all directions. The horse later turned up tied to a fence near town. Riders presented a bill for expenses including use of a “mile-a-minute automobile” for an hour at a cost of $60 (worth $1,680 today). The invoice was declared “horserageous” and denied.

Reliance companies everywhere declined over time. “By the 1940s and ’50s they began to fade as cars replaced horses,” said Kim. “Today they’re social companies dedicated to preserving history.” The Franklin Company continues to gather at the Plumsteadville Grange, one of the last farmers’ fellowship halls left in the county. It’s there members enjoy a bit of Blue Grass Music, a fine roast beef dinner and tales from the good old days.

Sources include “Susquicentennial Observance of The Franklin Company” published in January 2015; “Episodes in Bucks County History” by George F. Lebegern Jr. published in 1976; “Oldest Group in U. S. Reports No Horses Stolen at Dedham During the Past Year” published in the Daily Boston Globe on Dec. 3, 1936, and “Horse Thieves or No, Bucks County Possee Stands Ready to Ride” by Hal Maracovitgz published on Jan. 21, 1985 in The Morning Call newspaper. Information on the Newtown Reliance Company is available on the web at http://newtownreliance.org/