The story of a war hero from Bucks and the collapse of a ‘cursed’ theater.

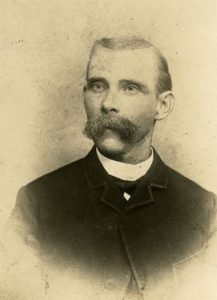

Samuel Banes witnessed Civil War horrors like few others from Bucks County. Gaines Mill, Chantilly, Second Bull Run, South Mountain, Antietam, Fredricksburg, Cloyd’s Mountain, New River Bridge, so many battles between 1861 and 1864. The warfare was numbing. He survived to return home to Bucks County a hero yet would die tragically years later in the Washington theater where Abraham Lincoln was assassinated.

I became aware of Banes’ story through Dave Detwiler of Warminster. He had just read an account of what happened in Civil War Times magazine. Dave suggested I take a look for a column. I never realized the theater, now a tourist attraction, had an amazingly “cursed” history. Also I was reminded of an old newspaper axiom: You can always find a Bucks connection to just about every important event in the nation’s history. Here was one of them.

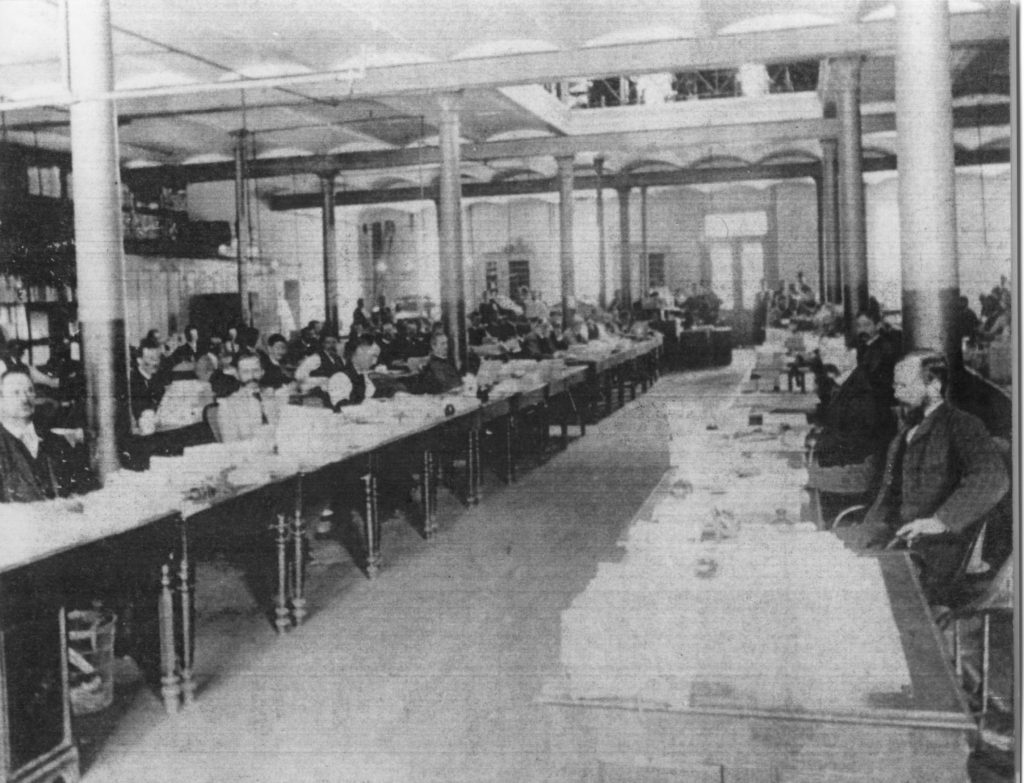

Young Sam grew up on Market Street in Bristol and like many teens rushed to enlist when the Civil War erupted on April 12, 1861. He joined the town’s Montgomery Guards, Company I of the 3rd Pennsylvania Reserve regiment. Sgt. Banes’ four years of bloody conflict took a toll on him physically. The War Department offered him a less stressful clerkship copying records archived in Ford’s Theatre. He worked on the second of three floors, crammed with desks and hundreds of fellow clerks who expressed worry about the creaky old building. One congressman described it as “absolutely dangerous.” Nothing was done.

The building was a Baptist Church when built in 1833. John T. Ford bought and converted it into Ford’s Athenaeum in 1861. Within two years it burned down but soon rose again as Ford’s New Theatre. That too became infamous on April 15, 1865 when actor John Wilkes Booth shot President Lincoln while he and his wife viewed the live comedy “Our American Cousin” from their balcony seats.

After the assassination, the U.S. government paid Ford $88,000 for the theater (about $2.5 million today) and closed it. For the next 21 years, it was a warehouse for War Department records on the first two floors, the third becoming an Army medical museum. In 1887, the entire building became a military archive. Among 500 clerks hand-copying records was Sgt. Banes.

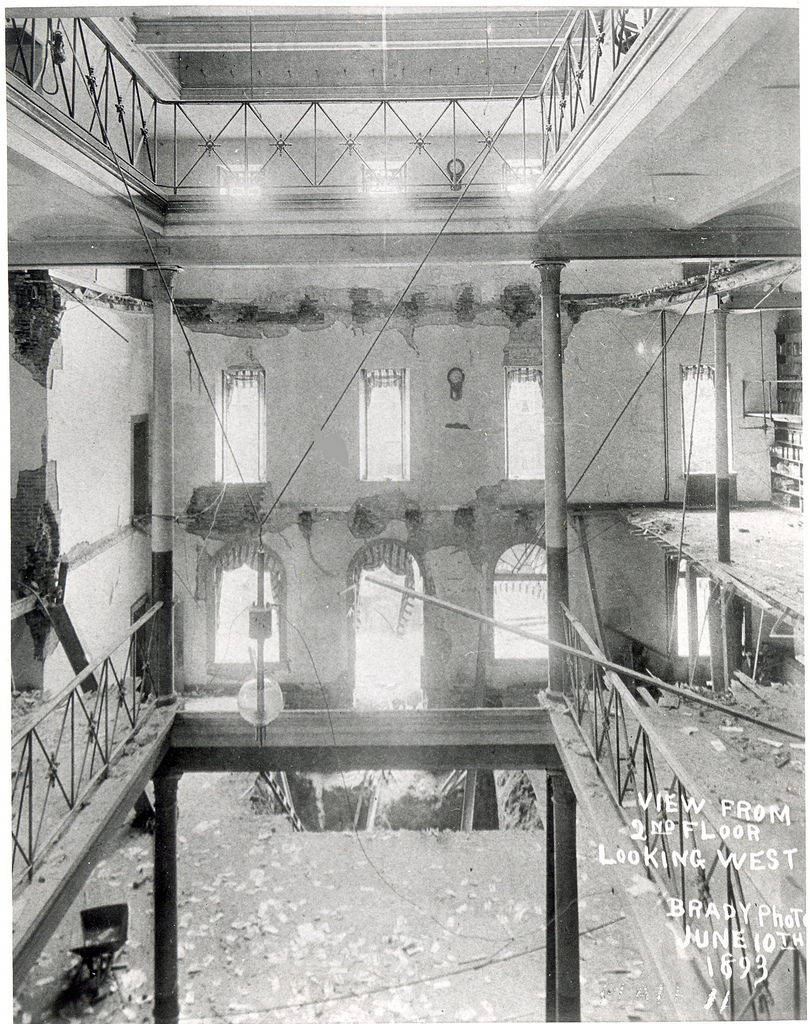

In early June of 1893, work began to excavate the basement for a generator to electrify the building. To make room, workers dug up building support piers while positioning a separate brace to secure the edifice. Clerks feared what was going on in the basement but continued transcribing records. What they didn’t know was the new bracing had been installed improperly.

Sam, in his 50s and described by others as helpful with a sunny disposition, showed up as usual on the morning of June 9 to wrap up the week’s work and look forward to the weekend. At 9:30 a.m. “a rumble like an elephant” emanated from the basement, freezing him at his desk. The bracing pier in the basement had given way, setting off a roaring cascade of wooden breams, bricks and mortar from the third floor and carving a massive chasm through the center of the building. Banes and others screamed as they disappeared into a “pit of chaos.” Surviving clerks on the third floor un-spooled a fire hose to slide down to safety as the building shook. A man on the street later hailed as “a noble Negro” climbed a telephone pole to drape a ladder from the pole to the third floor, enabling others to escape.

The disaster left the outer shell of the building standing with a gaping 40-foot-wide central hole. The collapse killed 23 and injured 100. Spectators stood in disbelief on the street. One newspaper reported men “wept like children” and “women were helped away in the fainting condition.” As for poor Sam, his body was pulled from the wreckage in the basement and shipped home for burial in Bristol. The Bucks County Gazette eulogized him the following week:

“As his mangled remains were laid to rest, the thought that he had passed unscathed through the dangers and privations of war, although bearing to the fullest degree his share and never shirking a single duty, only to be at this late day hurled into the abyss that yawned for him in the ill-fated building in Washington – that city which he had so bravely defended, forced upon the hearts of those who stood around his grave the truth of the Scriptural teaching – ‘For ye know neither the day nor the hour wherein the Son of Man cometh.’ ”

Banes’ family received a check for $5,000 from the government – equivalent to $132,000 today. In 1968, Ford’s Theatre was renovated and reopened for public entertainment. Today it’s preserved as Ford’s Theatre National Historic Site.

Sources include “Samuel P. Banes” published on June 15, 1893 in the Bucks County Gazette; and “Brick dust disaster” by John Banks published in the August 2019 issue of Civil War Times.