The Bucks County literary giant defied racial stereotypes in his lifelong identity quest.

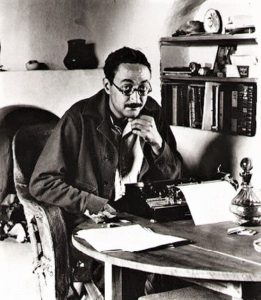

A few years ago, friend Tom Raski challenged me to find out why a highway passing through Doylestown and Buckingham is called Burnt House Hill Road. I drove it, called various historical societies and searched the Web for an answer. No luck. I made one discovery however: A farm on the road near the Buckingham border is where Jean Toomer lived. His name had faded from my memory as a novelist, playwright and a poet compared to the likes of Ezra Pound and t.s. elliott. Bi-racial, he could pass for white or Black but refuted all such characterizations. “I’m American,” he insisted.

I thought about this traveling abroad where my passport identifies me not by race but as an American. The cover features the Great Seal of the U.S. with its motto: “e pluribus unum” – “one out of many.” Toomer lived his life in that purpose. His accomplishments and legacy are memorialized at the Michener Art Museum in Doylestown plus archives at Yale and Tulane universities. New Yorker magazine recently eulogized him as a “religious omnivore” who drew around him “a revolving retinue of devotees.”

Nathan Pinchback Toomer was born in 1894 to a mixed-race former slave and mixed-race mother whose father was governor of Louisiana, the first African American to be elected that position in any state. Toomer grew up in Washington, D.C. where he attended Black segregated schools. Relocating to New Rochelle, N.Y. he attended an all-white school before returning to Washington and graduating from the M Street School, an academic Black high school with a national reputation. He studied agriculture, biology, sociology and history in six colleges between 1914 and 1917 but never graduated. What motivated him was reading the works of poets and novelists and attending their lectures. He began writing poems and stories and adopted “Jean Toomer” as his literary name.

After serving in 1921 as a Black school principal in Sparta, Ga., he authored “Cane”, a collection of stories and poems depicting African-American characters and experiences based on his time in the South. The book was a sensation, drawing broad accolades. “Most important Black poet”… “literary craftsman” . .. “haunting, illusive beauty” … “matched only in the best work of William Faulkner.”

He continued a prodigious career of publishing stories and poems but never with the commercial success of “Cane”. He lived in New York City’s Greenwich Village and was part of the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s. He also became interested in George Gurdjieff, a Greek philosopher and mystic who believed most people live in a state of “waking sleep” that can be elevated to full spiritual consciousness through certain routines including yoga-like dance called “The Work”. Toomer studied with Gurdjieff in France in the mid-1920s and became a disciple.

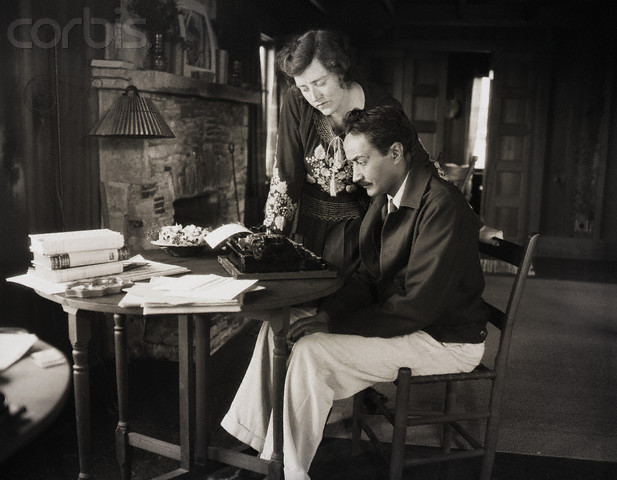

After marriage to novelist Margery Latimer in 1931, the two organized a Gurdjieff-inspired commune in Wisconsin, drawing interest from news organizations. She died the following year during child birth, leaving her distraught husband a daughter he named after her. Two years later he married Marjorie Content, a gifted photographer and daughter of a wealthy New York Stock Exchange member. Her friend and artist Wharton Esherik of Paoli suggested the couple move to Bucks. “We always admired Bucks County,” she later reminisced. “When Jean wanted to leave New York permanently, we began looking around in this area on Wharton’s suggestion.”

The family moved to a farm in Doylestown Township in 1935. Toomer soon organized a Gurdjieffian education center in the borough and became active in the Buckingham Friends Meeting throughout the 1940s. In the ’50s, he joined the New Hope Workshop that included wife Marjorie, Jo Jenks, Stanley Kunitz, Josephine Herbst and Jules Gregory. The literary group wrote and taught poetry.

The Toomers could not afford to set up a formal Gurdjieffian center on their Mill House Farm as hoped. However they introduced acquaintances to the experience. They performed manual labor at the farm as prescribed in Gurdjieff’s “Work” methodology. With the day’s chores complete, they would gather in the main house to enjoy adult beverages in what Toomer termed “deserving time”. As New Yorker magazine described it, “The placid hour wasn’t only for idle fun. Toomer – a brutally intense, relentlessly abstract, comically vain man who took every quotidian moment as an opportunity to philosophize – would ask probing, pointed questions, turning conversation into a kind of Socratic extension of his teaching.”

Jean Toomer passed away in 1967. His widow continued living at the farm until her death in 1984. Her husband’s quest for a melding of races into a singular American identity seems prescient given the racial divide of our times. As Swarthmore professor Richard Eldridge noted, Toomer always insisted “he was a representative of a new, emergent race that was a combination of various races. He averred this virtually throughout his life.”

***

Sources include “Jean Toomer’s Odd, Keening ‘A Drama of the Southwest’ ” by Vinson Cunningham published in the New Yorker on March 23, 2020; the Bucks County Artists Database at https://bucksco.michenerartmuseum.org/artists/jean-toomer; the Poetry Foundation at www.poetryfoundatoin.org/poets/jean-toomer; and a 1964 oral interview with Jean Toomer in Tulane University Archive’s Amistad Research Center.