How African-Americans lost the right to vote by what happened in Bucks County in 1837.

Who would ever guess that Bucks County led the way to deprive African-Americans of the right to vote in Pennsylvania for 32 years? It’s the most surprising and shameful historical episode I’ve ever encountered studying the history of our beloved county.

It’s rooted to the Oct. 10, 1837 election of six Bucks County office holders. Democrats lost all but one by very narrow margins. The candidate for auditor lost by just two votes. Officials blamed the setback on 24 black men who, they claimed, voted illegally. But the state constitution did not differentiate voting rights by race: “In elections by citizens, every freeman of the age 21 years and upward who has resided in the state one year preceding such election shall be entitled to vote in the county or district in which he shall reside.” At the time, many free blacks in Bucks had voted for years.

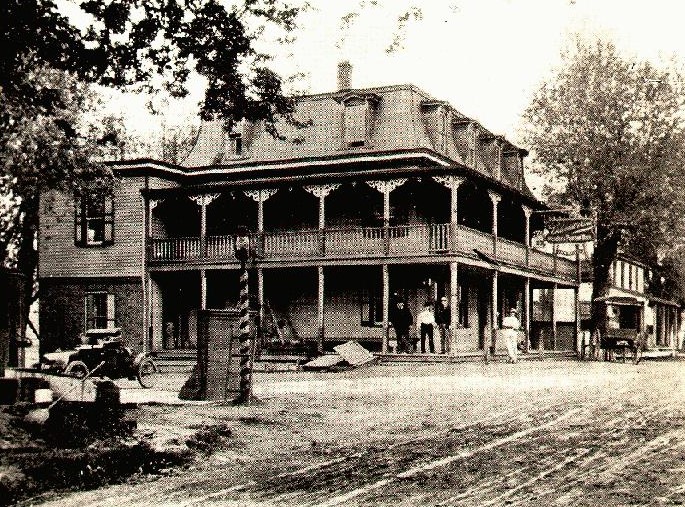

Local Democrats amplified their unsubstantiated charge, saying the men arrived at the polls packing rifles, threatening to shoot anyone who tried to block them. Others argued they simply brought their rifles to the polls like many others since Oct. 10 was the opening day of hunting season. The situation was so incendiary citizens, politicians and lawyers convened to plot strategy at the White Bear and Black Bear taverns in Richboro and the Buck Tavern in Feasterville. They contemplated a change in the state constitution.

Six months earlier work had gotten underway in Harrisburg to redraft it. John Sterigere, a Democratic delegate from Montgomery County, offered an amendment to restrict voting rights to “every free white male citizen” who has paid a state, county, road or poor tax. Phineas Jenks, a prominent Newtown physician and Whig party member, moved to strike the word “white”. Black property owners in Bucks had exercised their right to vote for many years, he said. To take that away from them would be improper. Others said basing suffrage on complexion was preposterous. Yet Democratic delegate Benjamin Martin of Philadelphia suggested black suffrage in Pennsylvania was a beacon to free blacks and runaway slaves from Southern states to move here and seize political control.

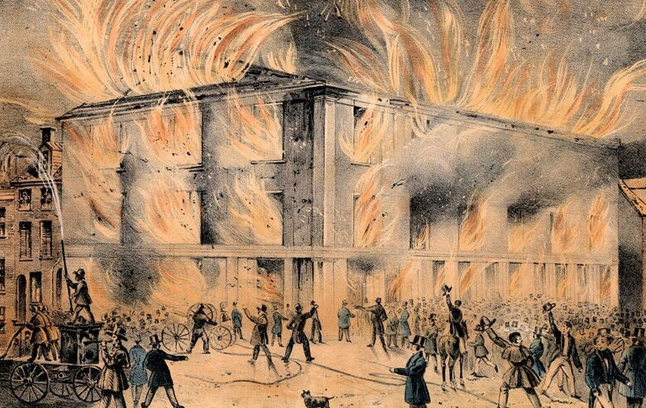

As negotiations continued in Harrisburg in May, a mob attacked Philadelphia Hall where famed abolitionists such as the Grimke Sisters of South Carolina, Lucretia Mott of Cheltenham and Robert Purvis of the Byberry section of Philadelphia could argue for an end to slavery and promote women’s rights. They never got the chance. The mob burned the building down just three days after it opened.

Back in Harrisburg, Sterigere’s amendment failed by a 61-49 vote. When the convention re-convened in the fall in Philadelphia however, the delegation had changed dramatically in favor of the anti-black lobby. After their stinging election defeat, Bucks Democrats turned to the convention to ban black suffrage. Signed petitions to that affect were submitted to the delegates. Sterigere championed them. As he put it, African-Americans should never be placed on a equal plain of “political and social rights with white citizens.” On Nov. 16, the convention voted 84-29 to accept the petitions. Subsequently, delegate Martin in January proposed the word “white” be inserted before the word “freeman” in the new constitution. He said a stark “divisionary line” existed between the races. To try to change that would invite “a war between the races.” Moderates were unable to prevail when the amendment came to a vote on Jan. 20. It passed by a 75-45 margin. Only 3 Democrats voted against it; 19 Whigs and Anti-Masons sided with 58 Democrats to push it through.

In the subsequent November general election, voters approved the new constitution by the narrowest of margins – 113,971 to 112,759. Free African-American males suddenly were disenfranchised throughout Pennsylvania for the next 32 years. Even after the Civil War, the restriction persevered. Though Union soldiers had fought and died to free the slaves, Pennsylvania remained a highly toxic place in terms of black suffrage. In the gubernatorial election of 1866, Democratic nominee Heister Clymer, a white supremacist, faced off against Union war hero Gen. John W. Geary, the Republican nominee. Clymer waged a race-baited campaign of fear; Geary did not take a stand on the issue, instead choosing to focus on what to do with Confederate traitors. The general barely won by 17,135 votes out of 600,000 ballots cast.

The state’s constitutional ban would remain in effect for another four years. In 1870, the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution finally established the right to vote for all African-American male citizens throughout the nation. It would be another 50 years before women also won the right to vote when the 19th Amendment became law in 1920.

Sources include the well-researched “The End of Black Voting Rights in Pennsylvania: African Americans and the Pennsylvania Constitutional Convention of 1837-1838″ by Eric Ledell Smith of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission published in the summer 1998 issue of “Pennsylvania History, and “Colonial Inns and Taverns of Bucks County” by Marie Murphy Duess published in 2007 by The History Press of Charleston, S.C.