Burning limestone transformed Bucks County in the 1800s.

In my college years, good friend Jerry Miller was earning his masters degree at the University of Florida. He’s the only person I’ve ever known to have his own kiln at home. It was a super hot brick oven about the size of a small refrigerator. There he turned out the most amazing pottery. That was about the extent of my kiln knowledge however.

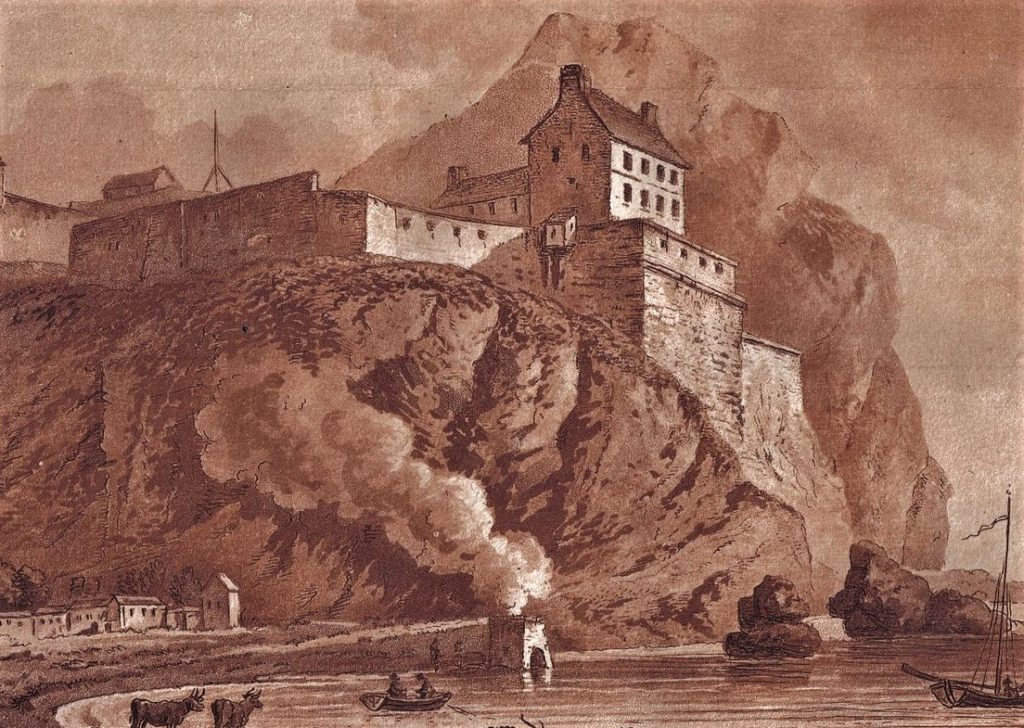

As a stranger to Bucks County after graduation, I happened upon Limekiln Road. It runs from Doylestown west to Lake Galena. Cool. So I’m driving along looking for the limekiln, or a limekiln store. Rats! Couldn’t find either. Turns out limekilns are altogether different from what I expected. They were enormous burners set in fields and against rocky cliffs. Scores, hundreds, perhaps more than 1,000 once were in operation in Bucks. So many, in fact, that Limekiln Pike (Route 152) from Sellersville in Upper Bucks to Philadelphia was a toll road built to serve 19th century kiln customers. All this activity put indigenous forests in danger of being clear-cut to fuel limekilns. Then something dramatic happened. But that’s getting ahead of the story. Lets go back to how this began.

In 1703 Larry Pearson gave his brother Enoch 200 acres of farmland that one day would become the village of Buckingham at the intersection of Durham and York roads in Central Bucks. There was one condition: Enoch’s deed stated he had “the privilege to get limestone from within granted premises, for the use of the said Lawrence and his children, their heirs and assigns forever.”

Wow! That limestone must have been valuable. Indeed it was. Lime was critical as a crop fertilizer to reduce soil acidity. It was used in tanning leather and as a white wash for homes and barns. It also was useful in treatment of burns, sore throats and removing warts.

So Enoch got to work scooping out limestone from a quarry at the base of Buckingham Mountain. The mineral came from two substantial limestone belts in Bucks. One passes from the Delaware River through Solebury and Buckingham to Wrightstown where it disappears below red shale. The other runs from the Delaware through Riegelsville, Durham and Springfield in Upper Bucks. All Enoch and Larry knew was limestone existed under the farm. Enoch built a brick kiln, fired by chopped hardwood. He and other laborers trundled quarry rocks that had been reduced with sledgehammers to bits no bigger than 8 inches in diameter into a wide funnel at the top of the kiln. That brought them to a grate over a red hot fire. Burning the limestone created powdered lime, a technology imported from England.

Bucks farmers began quarrying their own limestone wherever they could, such as a Colonial-era limestone quarry hidden in the woods at Playwicki Farm Park in Lower Southampton. As most of the county became agricultural, it was typical for a dozen or more farmers to gather at a limeburner to load up on fertilizer. A party atmosphere termed a “frolic” prevailed. Warren S. Ely of Doylestown recalled the scene in a 1910 memoir. “Many a jovial crowd of farmers, often from New Jersey, have I seen drive up to the old limekilns, unhitch their horses and feed them from the wagon bed, the loading of the wagons continuing meanwhile. Too often the free circulation of ‘liquid refreshments’ increased the joviality to a dangerous point, leaving the men unfit to guide their teams on the return trip over many miles of hilly and none too good roads.

Hardwood forests provided wood to keep kilns burning night and day. Then along came James Jamison of Buckingham. He discovered a new fuel: anthracite. The coal burned hotter and longer than firewood, reducing labor costs. The opening of the Delaware Canal between Bristol and Easton in 1832 made anthracite from upstate coal fields easily available and inexpensive. The limekiln industry flourished more than ever while sparing the forests. Lime-producing factories soon popped up astride the Delaware Canal. One was at the mouth of Riegelsville’s Durham Cave, using the cave as a limestone source. The village of Uhlerstown downstream in Tinicum imported limestone to be fired and sold in large quantities. And in Limeport on the canal in Solebury, many kilns created a bustling lime powder access for farmers in New Jersey, Bucks and elsewhere.

The advent of commercial fertilizers in the 20th century ended it all. Today, the old quarries and long-abandoned furnaces remain a curiosity. Fortunately historic preservation folks in Springtown in Upper Bucks are restoring a limekiln as a show piece on Woodbyne Road. It’s there you can imagine what life was like long ago when muscular laborers by the light of the moon kept kiln fires burning, helping turn wilderness into the beautiful farms we see today in our picturesque county.

Sources for this column include “Place Names in Bucks County Pennsylvania” by George MacReynolds published in 1942, and “Lime Burning Industry, Its Rise and Decay in Bucks” by Warren S. Ely read to the Doylestown (Quaker) Meeting on Jan. 18, 1910. An excellent description of the limekiln burning process is found on the web at http://monroehistorical.org/articles_files/1010_limekilns.html