Britain punished “the rebel Kirkbride” in Bucks County for what happened in Philly.

Josiah Kirkbride had this great idea.

As a runaway indentured servant at age 19, he accompanied William Penn on the first ship from England to help populate Penn’s new colony in 1682. He went to work on Penn’s 8,000-acre Pennsbury Manor in Falls Township, earning cash to buy real estate in the future Doylestown, Wrightstown, Perkasie and elsewhere. He also became Bucks County Justice of the Peace and member of the colonial assembly.

With the partition of Pennsbury in 1718, Josiah obtained a large swath along the Delaware River upstream from Penn’s mansion. There he had an epiphany: Start a ferry service to Bordentown, N.J. on the opposite shore. Josiah constructed a ferry house tavern, stables, a couple of homes and several out buildings. He called the main house Bellevue, French for beautiful view. Kirkbrides Ferry provided needed cash to support his 15 children in his long life.

During the American Revolution, Josiah’s grandson Joseph Jr. owned the river shuttle. As a colonel in the Bucks militia, he also raised troops for George Washington’s Continental Army. Junior was a close friend of Thomas Paine of Bordentown, a hot-bed of radicalism. Paine was a coffeehouse firebrand, an essayist who inspired the Revolution. In his view, the colonies would fare better economically if they didn’t have to pay onerous taxes to King George III.

Inspired in part by Paine’s impassioned rhetoric, George Washington famously crossed the Delaware from Bucks in 1776 to defeat the British at Trenton and Princeton. The Brits blamed Kirkbride and his ferry for aiding the general.

England struck back in November 1777 by sending the British Army and Navy up the Delaware from the Atlantic to seize Philadelphia. The overmatched Continental Navy fled upriver to hide in Bordentown’s Crosswicks Creek where plotters conceived an ingenious counterattack. At a local gun shop, townsmen filled 20 wooden barrels with gunpowder and flintlock exploders. The rebels carefully loaded the kegs, tethered together in pairs, into a whaling boat. After Christmas, the vessel negotiated the icy Delaware to a point just above Philadelphia 30 miles downstream. There in pre-dawn darkness, handlers gingerly set the kegs adrift on the outgoing tide, hopeful they’d smack British warships and explode.

The crew of a British barge was the first to spot them and pulled one aboard where it detonated, killing four sailors and injuring others. Immediately British ships unleashed furious cannon, musket and pistol fire throughout the harbor to destroy the bobbing onslaught. Shore bystanders thought it was a battle underway with rebels inside the kegs.

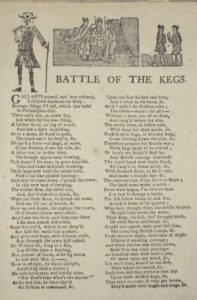

News of the attack spread through the colonies, giving a needed morale boost to the rebellion. In Bordentown, Francis Hopkinson was ecstatic. As a signer of the Declaration of Independence, he helped prepare the kegs and subsequently composed “The Battle of the Kegs”, a wildly popular ballad sung to the tune of “Yankee Doodle”.  The song made fun of how the proud British Navy went to war against floating kegs (though only the barge was damaged). “The canons roar from shore to shore, The small arms make a rattle, Since war began I’m sure no man, E’re saw so strange a battle.”

The song made fun of how the proud British Navy went to war against floating kegs (though only the barge was damaged). “The canons roar from shore to shore, The small arms make a rattle, Since war began I’m sure no man, E’re saw so strange a battle.”

Republished in England, “The Battle of the Kegs” incited political embarrassment. Parliament recalled Gen. William Howe from Philadelphia to explain the “defeat”.

Back in Philly, the Brits traced the kegs to Bordentown. In May 1778, a 1,000-man infantry boarded two gun ships and 20 flat-bottom boats for a shock-and-awe attack on Bordentown and “the rebel Kirkbride”. Redcoats quickly overwhelmed Bordentown defenses, killing 17 and wounding others. For the next few weeks, the enemy pillaged the city. Buildings were set afire and leveled. Military supplies, two Continental frigates and 27 smaller vessels were destroyed. Across the river, the British torched Kirkbride’s beloved Bellevue, his tavern, all outbuildings and the ferry itself. Nothing was left standing. The soldiers then marched south from the ferry landing on Bordentown Road through Tullytown to Bristol where they boarded ships for Philadelphia where just weeks later the British ended their occupation.

In a note to George Washington, Col. Kirkbride apologized for his absence to take care of his dislodged family, adding, “I had rather lose 10 such estates than to be suspected to be unfriendly to my country.”

The British attack on Bordentown and its ferry did nothing to soften resistence. Residents returned to rebuild better than ever. Joe Jr. had the resources to construct New Bellevue – in Bordentown. It was a glorious two-story mansion that stands today on a high bluff with a view across the Delaware to Pennsylvania.

In Falls, nothing’s left of Kirkbridesville. As best as I can figure, U.S. Steel’s Keystone Industrial Port at the terminus of Bordentown Road is where Joe Kirkbridge Jr. and the folks from Bordentown fought the good fight in the Revolutionary War.

Sources include “Ferries spanned the Delaware before advent of bridges” by Samuel C. Eastburn published in the Delaware Valley Advance in 1929; “Place Names in Bucks County Pennsylvania” by George MacReynolds published in 1942; description of the Bordentown attack published in the Pensylvania Ledger on May 13,1778. Also thanks to librarian Katherine Ludwig of the David Library of the American Revolution in Upper Makefield and Dr. Michael Skelly of the Bordentown Historical Society. Full lyrics of “The Battle of the Kegs” can be found at http://www.traditionalmusic.co.uk/song-midis/Battle_of_the_Kegs.htm