Looking back on West Niles and Yellow Fever.

In this age of pandemic, who can forget the West Nile scare of the summer of 1999?

I was in Boston in July of that year to discuss submarine warfare for an episode on the History Channel being filmed at Northeastern University. That afternoon, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health announced the first detection of deadly West Nile virus. It was traced to mosquitoes buzzing out of wetlands around the city. Huge headlines and breaking news announcements on TV created a pall over the city. I hopped a taxi and made haste for Boston Logan International Airport unfortunately out on the swampy breeding grounds. Fog was rolling in off the ocean. Flights were being cancelled including mine. A horde mentality took hold. Passengers made a mad flight from one terminal to another. I did my best imitation of the 100-yard dash and outdistanced most. I managed to elbow my way onto the very last flight out that night. Whew!

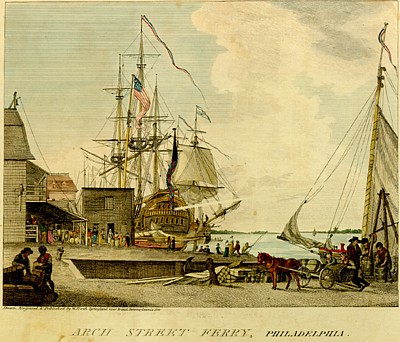

Staring down from my stratospheric window at stars on the land, I thought of how the City of Brotherly Love and Bucks County once was impacted by a crisis much like that of the West Nile panic. The pestilence arrived on a sailing ship from the Caribbean in August 1773. Within weeks, staying in the new nation’s capital was to risk a grizzly demise. Residents including President George Washington fled for their lives.

The ship that started it all – the British freighter Hanley – spread the disease at every port from West Africa through the Carribean and to the docks in Philadelphia. The first to die here was a passenger escaping a slave revolt in Haiti. First signs of the disease were skin and eyes turning yellow, followed by fever and vomiting black intestinal blood. Physicians were perplexed. Many blamed putrefying stocks of coffee beans on city wharfs. The mayor ordered a cleanup as “Yellow Fever” began its exponential rise.

John Dyer, a grist miller from Doylestown, noted in his diary on Aug. 27, 1793: “The yallow fevour rages dreadfully in the city, our accounts are that upward of forty thousands of the inhabitants left the city.” Philadelphia merchants Jesse Blackfan and Benjamin Ely evacuated with their goods and set up store in a schoolhouse in Buckingham. Methodist minister J.W. Winkhaus from Upper Bucks stayed in the city to help until his death from the illness. Dr. James Hutchinson, former state Surgeon General from Upper Makefield, succumbed after attending patients at the University of Pennsylvania hospital. Dr. Jonathan Ingham, a practicing physician residing at his childhood home at Aquetong Spring in Solebury, ventured into the city to care for victims. He too became ill and returned home. As his condition worsened, he left in a horse-drawn surrey to reach a mineral spring he thought might save him in Hunterdon County, N.J. Relatives along the route turned him away. No one at the spring allowed him in. He died. Unable to get assistance, his wife buried him outside a Presbyterian graveyard in Bethlehem, N.J.

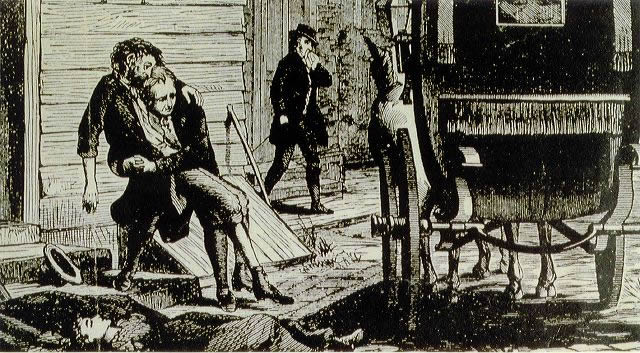

Back in Philadelphia, authorities advised residents to rest, stay out of the sun, avoid liquor and wear handkerchiefs doused with vinegar and camphor. Despite this, 5,000 perished in two months. City doctor Benjamin Rush experimented by using high doses of mercury and a poisonous Mexican root to purge patients of intestinal blood. Most perished.

Fear gripped the populace. “People hastily shifted their course at the sight of a hearse coming towards them,” reported eyewitness Matthew Carey. “Many never walked on the foot path, but went into the middle of the streets to avoid being infected passing by houses wherein people had died. Acquaintances and friends avoided each other in the streets, and only signified their regard by a cold nod.”

People of color, too poor to leave, heroically nursed the sick and carted corpses for burial. But they too succumbed at the same rate as whites. Absalom Jones noted, “A poor black man named Sampson went constantly from house to house where distress was, and no assistance, without fee or reward. He was smitten with the disorder, and died. After his death his family was neglected by those he had served.”

By September, residents hoped a hurricane would blow away the contagion. Instead, heavy rains produced an upsurge in cases. Cold weather finally ended the scourge in November.

The cause of the illness remained a mystery for 100 years. Finally in 1889, experiments by the U.S. Medical Army Corps in Cuba supervised by Dr. Walter Reed proved mosquitoes spread the disease. In the 1930s a vaccine finally came along. By then, it dawned on researchers that mosquitoes caused more human suffering than any other parasite. The list today includes Malaria, Chikungunya, Dog Heartworm, Dengue, Yellow Fever, encephalitis and what drew my attention in Boston – West Nile virus.

Sources include “History of Bucks County” by W.W.H. Davis published in 1905, “A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia, in the Year 1793″ by Absalom Jones published in 1794, “A Short Account of the Malignant Fever, Lately Prevalent in Philadelphia” by Matthew Carey published in 1794.