Henry Mercer would not be denied in his quest to display tools of Early America in Doylestown.

Every time the grand kids and I visit Mercer Museum in Doylestown we can hardly believe it. Where else can you stand in the atrium and view a whaleboat, Conestoga wagon, horse-drawn carriage and an antique fire engine suspended from the ceiling four stories overhead? Compartments with 50,000 reminders of Colonial implements used to build our nation are arranged around a winding walkway circumnavigating all seven floors of the museum.

Doylestown native Henry Chapman Mercer collected and categorized the artifacts. He was so passionate it led to a bitter feud with the Bucks County Historical Society which refused to display his works on a large scale. So he resigned. In the end he built this extraordinary cement castle where his one-of-a-kind collection is based today.

The historical society had long been the apple in the eye of Civil War hero William W. H. Davis who founded the organization in 1880. The retired general was a prolific journalist and author. As president, he set out to preserve the written history of Bucks County. Among those with Davis was 23-year-old Henry Mercer, scion of a prominent Doylestown family and a Harvard-educated history major. He later attended the University of Pennsylvania law school and joined the Philadelphia bar. His wealthy aunt Elizabeth “Lela” Lawrence of Boston supported him lavishly in life including trips to Europe to study archeology and anthropology, his life’s calling.

During his freshman year at Harvard in 1876, young Henry visited the International Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia celebrating the nation’s 100th anniversary. The fair was mind altering. Exhibitions included a massive steam engine that powered Machinery Hall where locomotives, typecasting machines, envelop makers, printing presses and other mechanical marvels foretold a national transformation. A separate exhibition of Early American life made a bigger impression on Henry. The contrast between the power of Machinery Hall and manual tools of the Colonial-era caused Mercer to worry the latter soon would vanish. Preserving them, he believed, would help visualize how the U.S. came to be.

In the late 1800s, Mercer began collecting old farm equipment, household tools and furniture, filling barns and other buildings in and around Doylestown. He also put together a modest display – “Tools of the Nation Maker” – next to the historical society’s meeting room in the county courthouse. Mercer intended to do much more, pressing for space in a courtroom or outside for a major display. Davis and especially Intelligencer newspaper publisher Alfred Paschall, a society co-founder, thought Mercer’s collection was worthless. They feared “heaps of old tools in and around society grounds would detract from their own work with written history,” according to Kathleen Ryan who detailed the feud in her well-annotated masters thesis at Lehigh University in 2002.

Turned away, Mercer staged an outdoor exhibition at Galloway’s Ford on Neshaminy Creek in Trevose. He hung various tools from tree branches and positioned large plows, carriages and work tools in the middle of an adjacent field. When steady rain spoiled everything, Mercer packed up and returned to Doylestown.

The Davis-Paschall faction continued to butt heads with Mercer while cancelling distribution of an 87-page catalogue of his collection. Paschall went so far as to forbid any mention of Mercer’s name in the Intelligencer. Society stalwarts also ruminated on Mercer’s “rather poor health” due to relapses from earlier illnesses. Much the loner and difficult to deal with in personal relationships, Mercer abruptly resigned from the society in 1898 and turned full attention to his budding Moravian tile business.

Seven years went by.

By 1905 Davis noticed surging historical society membership. He traced it to the “Tools” exhibition still on display at the courthouse. Davis reached out to Mercer, apologized for how he had been treated and welcomed him back. The general effusively praised Mercer’s work and denigrated Paschall for coming between the two men. Mercer accepted the apology and energetically rejoined the society. In defending his array of old implements, he declared, “Equipped with these very tools and utensils, the pioneer came to America. Armed with these he cut down the forest and worked out his life and destiny.”

Philadelphia businessman George Elkins in 1907 donated $10,000 to the society to build its own headquarters. The new Elkins Building on property a few blocks below the courthouse opened with enough space for a grander “Tools” exhibition.

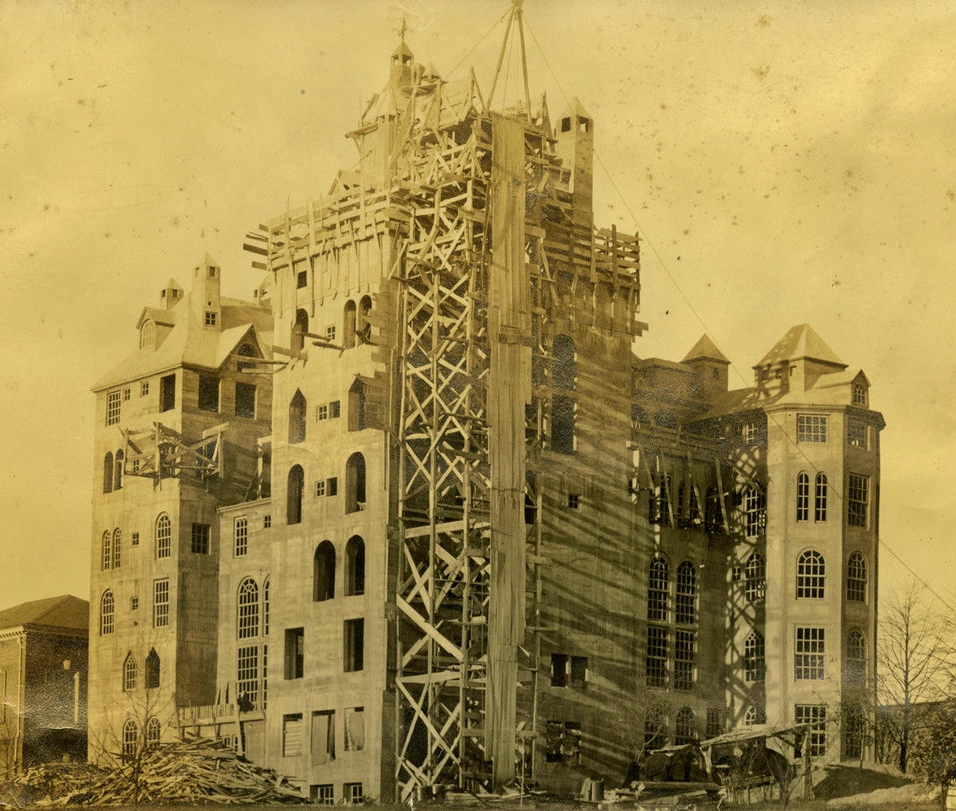

With Mercer moving up to society president following Davis’ death in 1911, he announced plans for a self-financed, 7-story castle made entirely of reinforced concrete. It would be a permanent repository for his collection. On opening in 1917, Mercer deeded the fire-proof colossus to the historical society. Without electricity, the museum contained many asymmetrical windows for daylight illumination. Mercer added a connecting ramp to the Elkins Building next door.

Thus was born what today is the unique and wonderful Mercer Museum.

Sources include the Bensalem Historical Society, “Henry Chapman Mercer: An Annotated Chronology” published by the Bucks County Historical Society in 1989; “Implements of change: Henry Chapman Mercer and the Bucks County Historical Society”, Kathleen Ryan’s authoritative master’s thesis for Lehigh University published in 2002 and available on the net at https