The historic stone in Solebury Township attracted quite a following in the 1800s.

I first got to know Robert Cleary at his home in D.C. My brother-in-law is one of those unforgettable characters you meet in life. He’s loud, passionate and funny with a dry wit. We were in our late 20s sharing some outstanding Japanese plum wine when all of a sudden he began reciting poetry in an Irish brogue. Maybe it was a sonnet by a Victorian poet. Thinking back to that moment, I like to imagine Bobby these days as a stout highlander with good hair in retirement with my sister Deb in Florida. He’s dressed in a kilt and sending up lazy rings of smoke from a Meerschaum pipe, all the while reciting memorized verse.

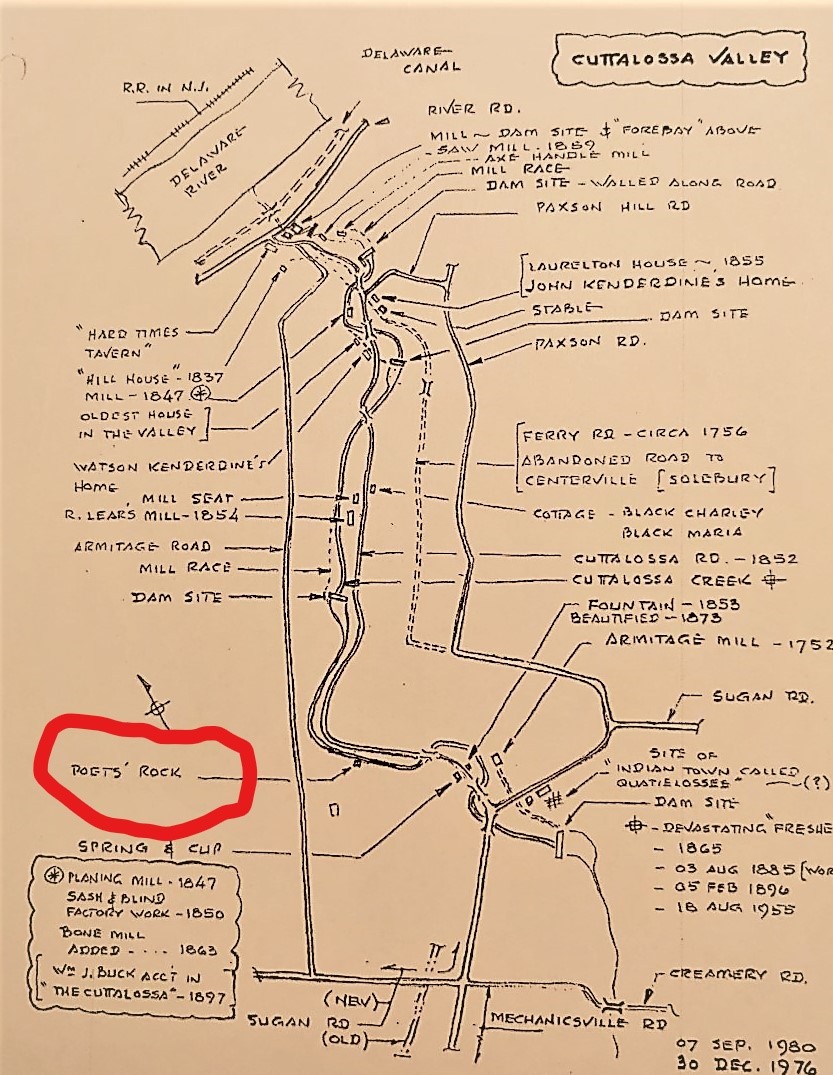

Just the other day we were doing a bit on Facetime when I mentioned Poets’ Rock in Solebury. He wanted to know more. To find the legendary stone, I told him, you have to climb down a steep incline, cross Cuttaloosa Creek on a rotting fallen tree or wade through slippery rapids. I chose the tree. The quartz stone is a short hike upstream through brambles. The rock looks like an ancient tree stump with a flat top, draped in green moss. I envisioned what it must have been like 150 years ago to stand on it reciting poetry before local bards gathered about you.

Poetry was important in the 1800s. Young and old focused closely on lyrics and what they evoked. Just about every newspaper in the land printed verse, rarely found today when folks prefer it in song. If there were a Billboard Top 100 in the 19th century, the entire list would be poetry.

One poet who inspired the Cuttalossa group was John Greenleaf Whittier. In the 1840s he moved to a stone house on Green Hill Road near Lumberville. Daily he’d walk a mile to the Delaware River village to pick up his mail, then hike back along Cuttaloosa Creek past Poets’ Rock. The narrow valley has an alpine feel to it with meadows lined by white sycamores and pine forests. Sheep and goats graze meadowlands as chickens forage near a waterwheel shelter. Historic homes and grist mill ruins dot the landscape.

As the “Quaker poet”, Whittier preferred wearing a plain coat and dark brown clothes. He was an avowed abolitionist and wrote diatribes against slavery. He barely escaped death from stoning when he was in his mid-20s in Concord, N.H. By 1837, he was a member of the Anti-Slavery Society of Pennsylvania and editor of the “Pennsylvania Freeman” published at Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Hall. A pro-slavery mob burned down the hall the following year, putting the poet to flight to Lumberville.

In fragile health most of his life, Whittier regained vigor on walks along the Cuttalossa where he pondered a rewrite of “Moll Pitcher and the Minstrel Girl” and found inspiration for “The Trailing Arbitus”, his eulogy to the early spring blossoms that “make the sad earth happier.” Looking back in 1873, he remarked, “I well remember the little river, its woodlands and meadows and the junction of the Cuttalossa with the Delaware.”

Two years earlier a group of local poets convened at Poets’ Rock to form a poetry society. It was Sept. 30, 1871. Many arrived by carriage, others on foot. One by one, they traded and recited their original poems such as “Legend of the Cuttalossa”, “The Pine Tree”, “My Native Land”, “Copper Nose” and “The Wood Thrush’s Song” inspired by five melodious birds tweeting above the gathering.

I clued Bobby into all this. He was so enthralled he plans to visit the rock with me this summer. We’ll cross the fallen tree and then wax poetic where young men and women once quested for lyrical fame. I challenged Bob to recite verse as good as Whittier’s from atop the rock. I emailed him a sample. Composed at Cuttaloosa, “Indian Corn” is an atmospheric ode to the growing season in Bucks. Here’s the opening:

Let other lands exulting glean

The apple from the pine,

The orange from its glossy green,

The cluster from the vine.

We better love the hardy gift

Our rugged vales bestow,

To cheer us when the storm shall drift,

Our harvest fields with snow. . . .

Bobby wasn’t impressed unfortunately. “I will send you some Gerard Manly Hopkins that will blast the Poets’ Rock into gravel,” he declared, adding, “My goodness, Whittier sure gets into some rather odd word usage: ‘Let vapid idlers loll in silk’ goes way beyond my ability to comprehend in the context of most of the rest of the poem. Maybe Whittier bumped his head on the rock one too many times.

“At any rate you got the party started so we can have an interesting exchange like men of letters in days long gone when we visit the stone.”

***

Sources include “Lumberville: 300 Year Heritage” by Willis Rivinus published in 2006; “Place Names in Bucks County” by George MacReynolds published in 1942; “The Cuttalossa and Its Historical, Traditional and Poetical Associations” by William J. Buck published in 1897; and “Historical Reminiscences of the Cuttalossa Creek in Solebury Township” by Thaddeus Stevens Kenderdine” written in 1926. Many thanks to the archives team – Judy, Pam, Wendy – at the Solebury Township Historical Society for aiding my research.