You might think we just lived it but nothing compares to 1816 in Bucks.

Seems like I’ve spent this past summer standing at the living room window staring out at lakes of rainwater. Beach trips cancelled. Biking and hiking plans shelved. Thoughts of building an ark have come to mind during days and nights of rainfall that’s boosted Bucks County’s annual total past 40 inches – 10 above normal. Then I came across the story of Charles Kirk of Warminster. Nothing quite compares to “the year with no summer” poor Charles experienced as a teenager. A tearful memoir he wrote late in life told the tragic story.

Kirk was one of 10 siblings growing up on a hardscrabble farm near Abington. His family struggled with poverty due to pastures greening later than normal for the second year. “I was so ashamed to be seen hauling hay in the spring of the year to feed our stock that I disliked to meet anyone, for it seemed to manifest to my mind a want of industry and management,” he recalled.

The year 1916 became progressively worse. “It was the coldest summer ever in the county, frost in every month. I remember well seeing the leaves on the hickory trees dead and crisp by the effects of it. Scarcely any corn came to maturity.”

The Kirks could not have known what caused it: a volcano 10,000 miles away. The top third of 14,000-foot-high Mount Tambora in Indonesia exploded on April 15,1815, killing 71,000 people. As the most powerful blast in recorded history, it left a caldera 4 miles across spewing enormous amounts of sulfuric ash into the atmosphere.

The plume spread around the world. A drop in global temperatures of about 1 degree Fahrenheit devastated agriculture. By the following summer of 1816, the Northern Hemisphere experienced dimming sunlight and lingering “red fog”. In Pennsylvania, lakes and waterways froze over in July and August. Successive waves of frost destroyed crops as far south as Virginia. Food shortages became widespread. In Ireland, famine took hold, augmented by an outbreak of deadly typhus spread by lice. In Europe, food shortages led to riots, arson and looting in major cities. In Switzerland, vacationing English novelists were so downcast by the gloomy weather they challenged each other to write the scariest horror story. Mary Shelley authored “Frankenstein” and John William Palidori “The Vampyre”, inspiring Bram Stoker to write “Dracula.”

Back in Pennsylvania, a real-life horror story unfolded for the Kirks. “It was the most sorrowful period of my life,” reminisced Charles. “So much so I scarcely refrain from shedding tears whilst writing these lines.”

Toward the end of the summer Rebecca Kirk contracted typhus.“The time of my mother’s sickness was an anxious one to all the family for she was indeed the head of it in every sense of the word,” her son wrote. “The fever at that time was thought to be contagious so us children were not allowed to go in the room where she was. But there was a crack in the board partition in the garret stairway that I used to go and peer through to see her. These are the last sights I ever had of her in this life.

“It was indeed a house of affliction,” he continued. “Sister Ruth took the fever and was dangerously ill for a long time. So much so that we were called in more than once to see her die, but after a long and tedious time she recovered. Sister Elizabeth, a girl about twelve, sickened and died in October. The rest of the children all took the fever (except Charles), eight of them sick in bed at one time.

“The neighbors became alarmed. Some were afraid to come amongst it but still there were some who rendered every assistance in their power. The doctors depended almost entirely on stimulants. Wine and brandy were used in large quantities. I had to go round and solicit persons to come and set up with the sick, and even this was a lesson of instruction to me. Never when any of the neighbors were sick not to be sent for but to go and see if I could be of any use.”

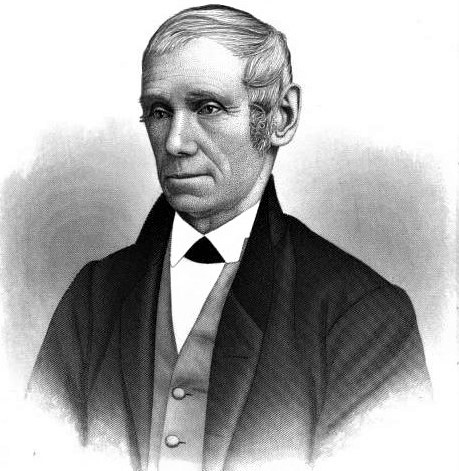

With his father disabled, Charles carried the awful burden of sustaining the farm and the family. Fortunately, the Kirks pulled themselves out of poverty as the seasons stabilized. In 1841 Charles purchased 118 acres in Warminster where he became a successful farmer and leader of the Quaker community. He was active in the Underground Railroad protecting slaves fleeing the South before the Civil War. In 1944, the U.S. Navy bought the farm which became part of the Johnsville Naval Air Development Center. After it closed in 1996, the farmhouse where Kirk is believed to have written his memoir still stood and became Gilda’s Club – on Kirk Road.

Sources include “Charles Kirk’s Journal” in the Bound Manuscript Collection at the Spruance Library in Mercer Museum, Doylestown; and “Blast from the Past” by Robert Evans published in Smithsonian Magazine, July 2002.