Legendary pedestrian of the 19th century made quite an impression crossing Bucks.

First time I saw a racewalker, I thought, “How odd.” One foot in contact with the ground at all times. The effect is to gyrate as your arms pump forward, giving you a side-to-side, twisting gait. Totally unnatural. Race walking was quite the thing in 19th century America in a country made “lazy’ by the rise of the automobile. Racewalking became a glamour sport. Spectators and gamblers filled fairgrounds and stadiums. Purses to winners could run as high as $300,000 in today’s currency.

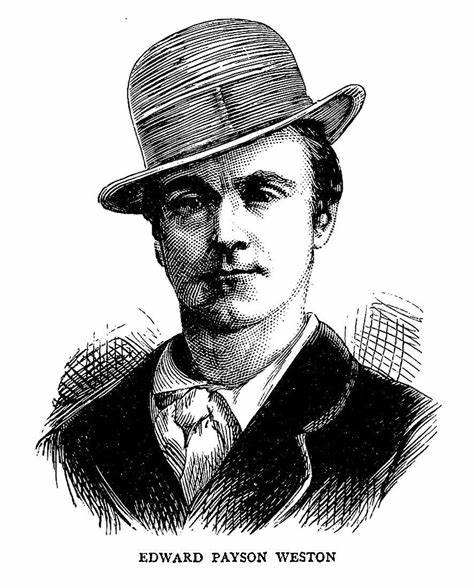

The man who popularized the craze was the Forrest Gump of his time – Edward Payson Weston. He made “pedestrianism ” famous in a celebrated race that passed through Bucks County in 1861. “Weston the Pedestrian” thrived in a sport transplanted from England where it had been popular for decades.

As a youth, Ed was a sickly child born to an affluent Providence, R.I. couple. Ambitious in his teen years, he started his own publishing business featuring books about his father’s adventures in the California gold fields. All the while he was dreaming up self-enrichment schemes. On a lark at a dinner meeting in Boston when he was 22, he wagered that Democrat Stephen Douglas would win the 1860 presidential election. He lost. The stakes: Weston had to racewalk 500 miles from Boston to Washington in 10 days to see Republican Abraham Lincoln inaugurated. Using his biz savvy, Weston lined up sponsor Grover & Baker Sewing Machine Company to ensure maximum publicity. He also hired two witnesses to follow him in a support carriage.

At 12:48 p.m. on Feb. 22 Weston got underway. Lincoln would be sworn in at 12:48 p.m. 10 days later. Weston encountered snow two feet deep in Massachusetts plus rain, mud and slush in Connecticut. Well-wishers and a brass band greeted him along the way. Young women lavished him with kisses to be “relayed to the president.” He ate as he walked, “munching on sandwiches offered by villagers.”

Reaching Trenton, he slept for 6 hours, then crossed the Delaware to Morrisville and headed south on today’s Old Route 13 to Bristol where public fervor ran high. Seven days earlier, Lincoln stopped in the borough where the president-elect addressed school kids and others from the back of his inaugural train. Weston’s approach on Feb. 29 again brought out Bristolians to cheer his passage on the two-mile, north-to-south length of Pond and Otter streets. Near the intersection of the two streets not far from where Lincoln made his stop, Weston encountered Joseph Tomlinson outside the Exchange Hotel. Joe was one of Bristol’s most distinguished residents, known as a speedy walker. He sidled up alongside Weston and both proceeded down Otter Street neck-and-neck at a spritely pace. The crowd roared. According to one witness, “Weston finally turned to Tomlinson and said at the Otter Creek bridge, ‘Well, old man, you are a pretty good walker, but I’ve got to leave you. Whereupon he made a spurt and to the great surprise and mortification of Tomlinson, was far in the lead.”

Poor Joe dropped out and stared with incredulity at the fast-disappearing Weston who made it to Washington on March 4 but four hours too late to catch Abe’s inauguration. Weston later shook hands with the president at his inaugural ball. Lincoln offered to pay for his train trip home. He declined, returning the way he came – on foot.

A champion of the health benefits of walking, Weston the Pedestrian turned professional in 1867. He was a dandy, favoring black velvet knee britches, blue sash, white silk hat and kid gloves when racing. He performed his fetes all over the country. In 1871, he racewalked backwards for 200 miles around St. Louis. Uninvited walkers occasionally joined his treks for short bursts. He would go on to race in England where he became world champion.

At age 70 in 1909, he completed a 4,000-mile walk from New York to San Francisco in 104 days. Failing to achieve his 100-day goal, he replicated the walk in reverse the following year – from Santa Monica to New York City in 90 days. The Daily Herald newspaper reported his arrival on May 3, 1910: “Five hundred thousand people crammed New York’s most famous thoroughfare today to see one white-haired man march through their cheering lines. The man was Edward P. Weston, and the ovation he received was the greatest ever accorded to any man not connected with public life.”

Weston would live to 90, unable to walk since being hit by a taxi two years earlier. Back in Bristol, the memory of Tomlinson’s encounter lingered. Local historian Doron Green noted in 1911, “ ‘Uncle’ Josie Tomlinson is remembered today by many of our citizens, and if ‘Weston’ could surpass him in speed as a walker, all agree that he must have been far above the average.”

Weston-by-the-miles

1861: 478 miles from Boston to Washington (passing through Bristol) in 10 days.

1867: 1,200 miles from Portland, Maine to Chicago in 26 days; prize $10,000.

1871: 200 miles walked backwards around St. Louis.

1876: Spent 8 years in Europe competing in high stakes race walks.

1906: More than 100 miles from Philadelphia to New York in less than 24 hours.

1907: 1,200 miles from Maine to Chicago at age 68 in less time than his first trek.

1909: 4,000 miles from New York to San Francisco in 104 days.

1910: 4,000 miles from Santa Monica to New York in 90 days.

1913: 1,546 miles from New York to Minneapolis in 51 day.

Sources include “A History of Bristol” by Doron Green published in 1911; “The World’s Greatest Walker” by Paul Marshall and Nick Harris found on the Web at wwww.sportingintelligence.com;“The Pedestrian”, a 48-page pamphlet published in 1918 about Weston’s trek between Boston and Washington on file at Cornell University Library; plus help from Bristol historians Carol and Harold Mitchener.