New book reveals how a roving handler and his spies secured U.S. military secrets.

I’ve snagged many interesting Bucks County stories to tell over the years. Somewhere near the top is a reminisce from Katharine Ritter Wallace of McLean, Va. Her father recruited and supervised Nazi espionage agents in Britain, America and North Africa from 1936-1941. Their aim was to swipe aviation secrets. Katharine hoped I could resolve a question about Col. Nikolaus Ritter’s rendezvous in 1937 with his Doylestown agent working at a nearby seaplane factory “on the Susquehanna River”. I chuckled. “Your dad probably meant Fleetwings Aviation on the Delaware River in Bristol. Seaplanes were built there, only 30 miles from Doylestown.”

Katharine had been translating into English her dad’s German memoir, an insider’s view of being Adolph Hitler’s spy handler. “Cover Name: Dr. Rantzau” was recently published by Kentucky University. An advance copy arrived at my doorstep a few weeks ago.

Ritter was a wounded German infantry officer in World War I who emigrated to the U.S. in 1924, became a businessman, gained fluency in Americanized English, married a schoolteacher and fathered two children. In 1935 the family left for Germany, in part so the kids could meet their gravely ill paternal grandfather. That year Ritter joined the Abwehr (“Repulse” in German), a new intelligence agency of the Third Reich. As chief of air intelligence, Ritter’s assignment was to gather data on enemy airfields, aircraft and state-of-the-art technology. Ritter’s grasp of English made him ideal as a roving spy recruiter and organizer. He used many aliases while drifting around Europe and the United States. In Holland, he was Dr. Rantzau. In Belgium and Luxembourg, Dr. Reinhard. In Hungary, Dr. Jansen. In the U.S., Alfred Landing or simply “Mr. Johnson.”

In 1937, Ritter returned to the U.S. to meet individually with his spies. Within months he personally secured plans for Norden Corp.’s ultra secret bombsight and Sperry Corp.’s gyroscope that he smuggled back to Germany. Both would help propel Hitler’s Luftwaffe into the world’s most devastating air force by 1939.

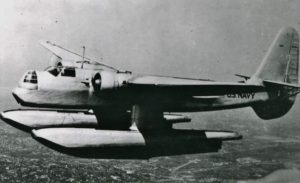

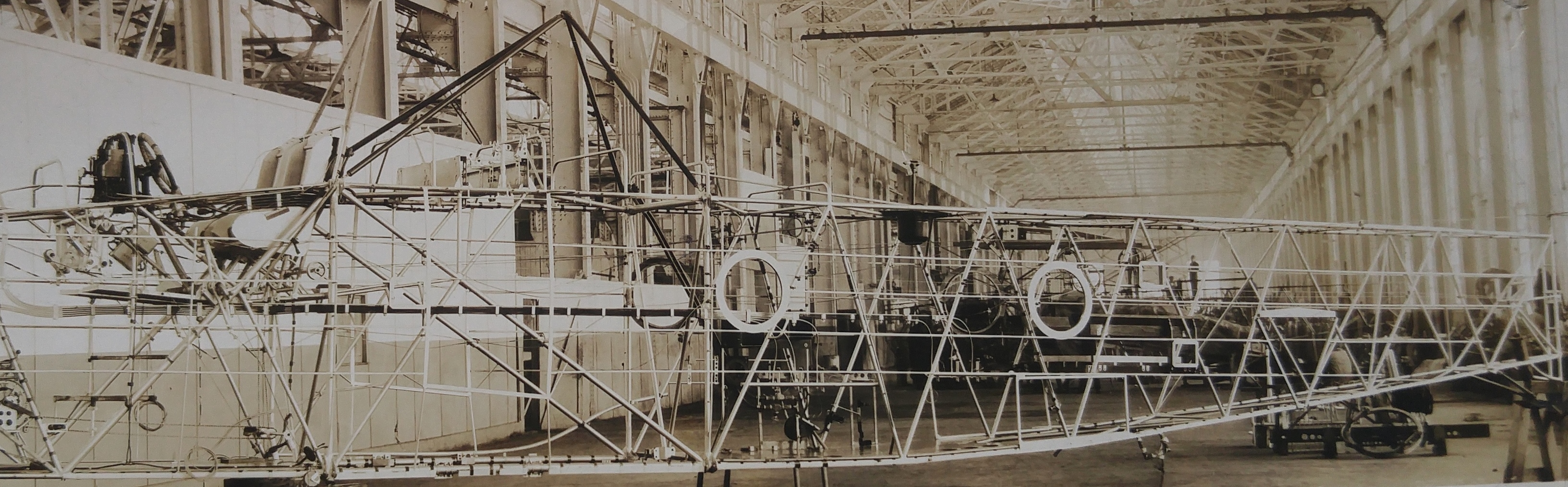

During his spy-to-spy tour, Ritter arrived by bus in Doylestown to see one of them. He was at work but his wife offered to drive the colonel to the factory which she said was building “flying boats for the Navy.”

“Is just anyone allowed to drive in there?” he asked. “ ‘Why not?’ ” she replied. Stopping at a coffee shop outside Fleetwings, a waitress mistook “Mr. Johnson” for a new employee. Then a “short, lively man in shirt sleeves came in, saw me, sat next to me, and greeted me in German like an old acquaintance. ‘You are Mr. Johnson?’

“I delivered regards from (codename) ‘Kurt’ in Hamburg, and told him that Kurt was wondering why he had not heard from him for such a long time. ‘That’s just like him,’ the little fellow laughed. ‘Well, we did not have anything for him in the past two years.’ ”

Ritter braced as the agent openly discussed in German things “that should have been secret. He made fun of my dismayed expression. ‘Calm down,’ and pointed toward the hostess. ‘Annie here can listen in on everything. First of all, she doesn’t know a word of German, not even Pennylvania Dutch. . . Come on. Let’s go over, and I’ll show you the shop.’

“I had to gasp for air and went along with him.”

The facility was old. “The little fellow saw how disappointed I was. ‘Don’t worry,’ he said. ‘Now everything is being modernized. We have a big order from the naval air arm. Let’s get over there and take a look at the model boat.’ ”

Which they did without interference.

Out of earshot, the two discussed how intell should be handled. The spy was reluctant to send it by mail to New York; a flurry of letters might raise suspicion. Ritter suggested St. Louis. “You’ll get your re-routing address as soon as possible, but to begin with, we must do a careful trial run. First, just write two harmless letters so we can see if everything is clear. Then, we can begin with your confidential reports.”

“ ‘How am I to send them?’ he asked. Microphotography. . . . I’ll send you an agent who will initiate you in the mysteries of microphotography, and from then on, don’t use anything else for your reports.

Mr. Johnson bid “auf wiedersehen” and boarded a train for St. Louis.

Unfortunately for him, one of his recruits became a double agent, leading the FBI in 1941 to take down the espionage network dubbed “The Duqesne Spy Ring” after one of the agents arrested. Thirty-three were convicted. Ritter evaded capture and was reassigned to German air defenses. After the war, the British incarcerated him for two years. He then faded from the scene until his family urged him to write his memoir before his death in 1974. Thanks to his daughter, the conversational account at last tells his story for an American public.

Sources for this column include “The Game of Foxes” by Ladislas Farago published in 1972 and the well-annotated “Hitler’s Undercover War – The Nazi Espionage Invasion of the USA” by William Breuer published in 1989. Additional thanks to George W. Bintliff III whose father worked at Fleetwing Aviation, and Katharine Ritter Wallace.