He treasures a railroad wonder that a Doylestown man helped build.

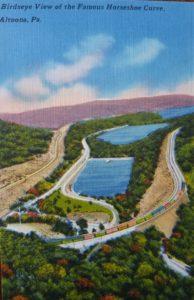

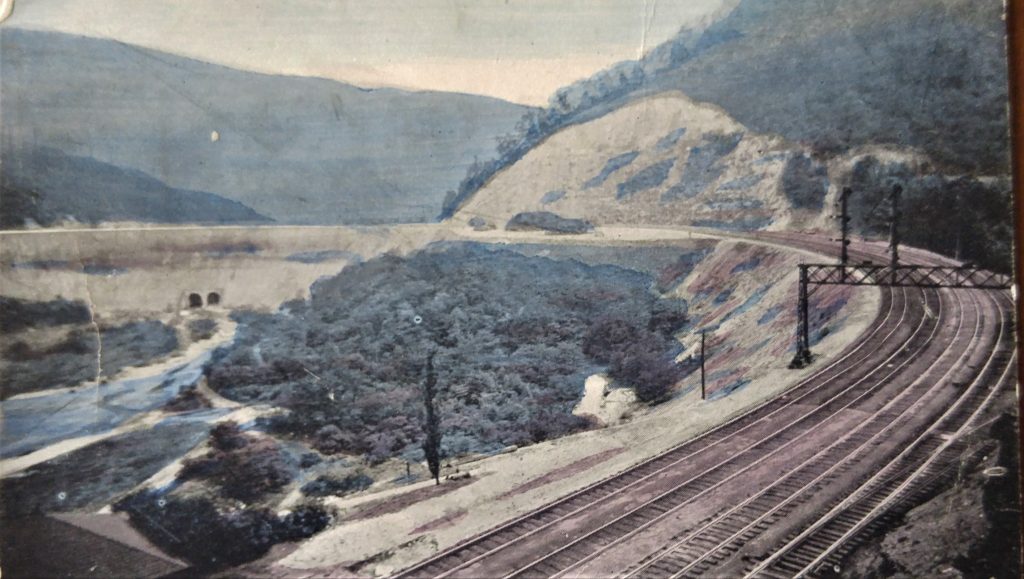

You mention Horseshoe Curve and Neil Wood of Levittown gets animated. Neil is a retired Northern Burlington County (N.J.) history teacher and librarian with a strong sense of wanderlust for the railroad industry. In his lifetime he’s visited the Curve near Altoona at least 150 times in the past 55 years to watch freight trains pass at 15-minute intervals through the Allegheny Mountains. Neil and I, like many afficionados, consider Horseshoe Curve a sort of Holy Grail of railroading. The engineering feat was considered one of the Seven Wonders of the Modern World when it opened in the mid-19th Century.

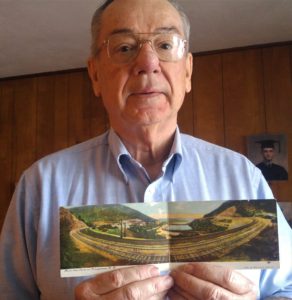

On my visit to Neil’s home, we viewed on his computer a Virtual Railfan live feed of three trains simultaneously rounding Horseshoe Curve. “As a kid, I always wanted to go see it,” Neil reminisced, the very visage and voice of screen actor Walter Matthau. “Dad thought I was crazy to go watch trains so we never did go.”

After high school in Towanda, Neil enrolled at Penn State, 40 miles from Altoona. “So I said to myself, ‘By golly, I’m going to Horseshoe Curve.’ ” And he did. It was his first weekend at school. He caught a Greyhound bus, then a city bus, then hiked up a 7-mile tourist road. The owner of a refreshment stand on the Curve picked him up, shortening his trek and providing free snacks. Arrival was an epiphany. Within minutes a 100-car freight struggled upgrade around the curve, six diesel engines pulling and six more pushing amid the squeal of wheel flanges on the tight curvature of the rails.

In our conversation, I managed to add a small nugget to Neil’s knowledge: A Doylestown man helped build Horseshoe Curve.

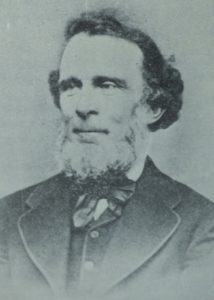

Philip K. Fretz, born in 1813 in Fretz Valley of Doylestown, was a humble, hard-working man with a jovial disposition. Said one acquaintance, “To write of him as he was known is to write of the day-by-day life of the earnest-loving Christian who had at heart first his township, then his county, next his state and finally the best country that God Almighty ever made.”

Phil closed his Wheat Sheaf Inn in the valley in 1846 to join brother-in-law John Farren as contractors building coal mine railroads in upstate Pennsylvania. In 1851, the duo headed for Altoona to help breach the Allegheny Front for the Central Penn Railroad. The 2,000-foot-high massif had long impeded travel. It once took a full two weeks by stagecoach to reach Pittsburgh from Philadelphia due to those summits. Horseshoe Curve was designed to reduce the time to a single day.

From Altoona, Fretz and Farren helped map out 45 miles of curves and tunnels through the mountains that enabled long trains to gradually increase elevation to 1,650 feet before breaking through to the other side. The largest of the loops was Horseshoe Curve. For two years 450 laborers from Ireland completed the task using picks, shovels, wheelbarrows and blasting powder to cleave entire mountains. When the route opened in 1854, historians hailed it as one of the Seven Modern Wonders of the World.

Fretz returned home just as a deadly cholera epidemic hit Doylestown’s Almshouse. He moved his family up county to Erwinna out of danger, then returned. No one but Fretz volunteered to aid patients or bury the dead. The poorhouse superintendent came down with the illness. So did his son who died. “Being unable to find an undertaker who would bury the steward’s young son, (Fretz) secured a hearse and buried the lad himself,” according to historian William H. Davis.

After the Civil War, Fretz boarded a steamship to visit two brothers in California. Off the Carolina coast on March 13, 1867, he died and was buried at sea. His son Philip H. became a San Francisco banker and later built one of the finest mansions in Bucks County, today’s Tabor Home for Needy Children in Doylestown.

As for Horseshoe Curve, it remains a vital portal to the continent. In World War II, trainloads of troops and armaments moved steadily through the pass to East Coast ports for trans-shipment to Europe. The rail line was so important a regiment of soldiers stood guard to prevent threatened sabotage by Nazi agents captured in Delaware.

In 1947 after the war, a horrific accident occurred on a sister curve when an express streamliner bound for New York jumped the tracks and tumbled into a chasm, killing 22 and injuring many.

Today Neil Wood, who has made a hobby of photographing coal mine railroads, wistfully contemplates relocating to Altoona. There he would enjoy a drive up to the Curve to watch in child-like wonder as 40-50 freight trains pass in a single day. To him that would be railroad nirvana.

Sourcing for this column includes “History of Bucks County, Pennsylvania, from the discovery of the Delaware to the present time”, Vol. 3 by W.W.H. Davis published in 1905, and “The Horseshoe Curve: Sabotage and Subversion in the Railroad City” by Dennis P. McIlnay published in 2007.