Remembering the ‘Norman Rockwell’ of Bucks who refused to toot his own horn

“Patsy Drew walked down the library steps directly into the effusive embrace of Eleanor Fitz-Henry. ‘Darling!’ exclaimed the red-haired Eleanor, looking more radiant than ever in her green early-spring outfit, ‘You’re an answer to a prayer!’ Patsy’s gray eyes widened inquiringly. Eleanor came to the point with her usual directness. ‘I’ve been wracking my brains to think of some girl I could trust Neil Allison with for one evening.”

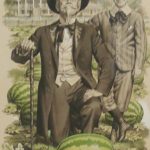

This was the opening of a romance story published in Philadelphia Inquirer Magazine on Nov. 8, 1959 under the headline, “Patsy, a modern Cinderella, takes rich girl friend’s place on a date.” Something more was needed to captivate readers however. Namely a portrait of the winsome Patsy. No problem. Enter Walter “Cal” Calvert of Buckingham. As a freelance artist then in demand by pulp mags, all Cal needed was a copy of Ruth Hunt’s tale. From it he quickly envisioned a Liz Taylor-like Cinderella getting ready for her big date as modeled by his daughter Judy.

Calvert was a mainstay of the American magazine industry in the mid-20th century. Though well known in Bucks County’s art community, Calvert remained largely unknown nationally. He deflected praise and often would not sign his works. Said wife Eleanore after his passing in 1960, “Had Cal been a better businessman, his name would be as recognizable as Norman Rockwell.”

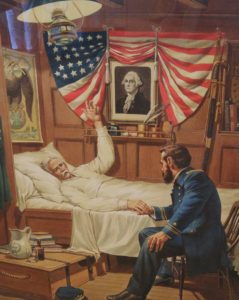

It’s easy to mistake some of his works as those of Rockwell. But Calvert can’t be pinned to one style. As an artist for hire, he could quickly turn out images to fit the stylistic demands of his employers. A graduate of the esteemed Philadelphia Museum School of Art in the mid 1920s, his work appeared on many magazine covers from the 1930s through the 1950s. They included the Saturday Evening Post, Country Gentleman, Sports Afield, Bell Telephone News, Bucks County Traveler, Pennsylvania Railroad and the Farm Journal. He also was active in national advertising campaigns.

Recently a retrospective of Calvert’s career completed a month-long run at the Doylestown Historical Society. It was a tribute to one of the lesser known greats of the Bucks’ art world. The idea for the exhibition came as a bolt of lightning to Milton Kenin, senior archivist at the society. He was thumbing through archives and noticed a photo published in a 1956 Central Bucks High School yearbook of Calvert’s daughter Judy pointing to a painting by her father on the school wall. The acrylic depicted in exquisite detail a 1913 flag-raising at the former Doylestown Public School. Wanting to know more about the artist, Milt tracked down Judy at her home in Solebury where she lives with her husband George Yerkes. Her father’s works decorate their house. Kenin was “blown away” when he first saw them. “So I invited her to exhibit them at our headquarters to help resurrect his career,” said Milt. With that, the couple assembled about 40 works of art and headed for the historical society.

Recently I caught up with Judy at her home on a wooded cliff overlooking Lumberville and the Delaware River. There we talked about her dad and living on a farm in Buckingham adjacent to Yerkes family’s None Such Farm. That’s where her husband George grew up and became a Navy combat pilot in the Vietnam War. “We’ve known each other since I was 3 and he was 7,” she smiled.

As an artist, Calvert was so committed to his craft he’d start work at 8 a.m. and continue in his at-home studio until 3 a.m. the next day. But he made time for family. “He was the most wonderful, kind gentleman as a father,” Judy smiled. And creative. He loved the outdoors, reflected in many of his paintings. “He made a whole playhouse for me and my sister Carole out of sunflowers. He planted them for walls and rooms and then when they grew and bloomed we walked inside and it was magical looking up through the flowers.”

When not painting, Calvert and his wife bought old farmhouses in Bucks and fixed them for resale. Being a prolific artist was Cal’s passion. He poured himself into each canvas, whether it be scratch board, pen and ink, pastel, acrylic or oil. He nor his wife knew how to make a business of art however. To Judy, it’s understandable. “Most artists have trouble selling their art work,” as she put it. For that reason, Cal never achieved the kind of national fame earned by George Sotter, Daniel Garber, Norman Rockwell and Ben Solowey whom Cal knew.

Judy in retirement would like to see the legacy of her dad perpetuated. To me, an exhibition at the Michener Art Museum in Doylestown would seem likely. Or Judy could take the collection on the road. “Not a chance,” she laughed.