The day a steam locomotive train set a world speed record in Bucks County

“Yes it can.” “No it can’t.”

The argument was whether a passenger train could reach 90 mph. The chaffing occurred in the late summer of 1891 at a ritzy gathering of the Farmer’s Club in Easton. State Supreme Court Judge Henry Green was going nose-to-nose with Walter Angus McLeod, president of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad Company. The two were arguing about steam locomotion’s upper speed limit. This was before automobiles, before aircraft. Back then, the common form of transit was horse and buggy. You were lucky to make 20 miles per hour at best. As for railroads, locomotives in the 1890s could approach 80 mph. But 90, pulling a train? Impossible, argued the judge.

McLeod was more than up for the challenge however. He had worked his way up the ranks of the railroad to become its chief executive. In doing so, he had reinvigorated the line which had begun to fade. He invested in new tracks and anthracite coal mines to power a new generation of locomotives. McLeod also built the renowned Reading Terminal in Philadelphia, adding luster to his railroad.

In accepting Judge Green’s dare to attempt a world speed record, the first step was putting together a steam train. McLeod chose Engine 206, one of the Reading’s fast, reliable locomotives of the Wootten class with nearly 6-foot-high driving wheels. For the trial, the engine would be hitched to a coal tender, two regular passenger coaches and “The Reading”, McLeod’s luxurious private coach weighing twice a regular coach.

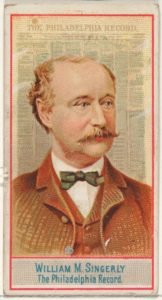

McLeod invited his friend William Singerly, publisher of the Philadelphia Record newspaper, and a clutch of reporters to be aboard as witnesses. Singerly, whose father founded Philadelphia’s street car system, loved trains. For the previous 13 years his hobby was timing their speed. Rarely had he measured any doing 50 seconds over a measured mile. That would be 70 miles per hour. To do, 90? Maybe. Singerly was eager to be aboard to certify the speed of such a “fly”, as railroad folks called a fast train of that era.

McLeod chose a 10-mile stretch of tracks passing north by Bensalem’s Neshaminy Falls station and Middletown’s Langhorne station on the Reading’s Bound Brook spur line between Philadelphia and West Trenton, N.J. Gaining a running start out of Philadelphia, the train steamed toward Neshaminy Falls on Oct. 21. Gaining momentum, the depot came into view. Singerly clocked every passing mile as Engine 206 roared past, a chugging monster of steel laying a ribbon of smoke over the coaches trailing behind.

No one at either station had witnessed anything like it. In McLeod’s private coach, Singerly noted the time at each mile marker, edging closer and closer to the 90 mph goal. To reach it the train had to cover a mile in 40 seconds. On the second mile of the run, Engine 206 hit the mark at 39.8 seconds – a shade faster than 90 mph. As the train slowed after its run, Singerly calculated the train had established a trio of world speed records:

Fastest mile – 90.6 mph on the second mile.

Fastest 5 miles – 87 mph (3 minutes 26.8 seconds).

Fastest 10 miles – 84 mph (7 minutes 12 seconds).

Like Chuck Yeager and his Bell X-1 rocket ship breaking the sound barrier in 1947, the “flight” of Engine 206 made headlines everywhere. The Washington Star newspaper declared Engine 206 built in Reading, Pa. “a triumph of the skill of American mechanics.” Engineer John Hogan and fireman Oscar Feshner who controlled the engine’s steam boiler were feted as heroes. The Forest Republican, a newspaper in coal counatry’s Tionesta, Pa., headlined the news simply, “Ninety Miles an Hour!”

The new question was how long it would take before a passenger train pulled by a steam locomotive reached 100 mph? It would take 43 years. On Nov. 30, 1934 the Flying Scotsman notched the century mark on the East Coast Main Line of the United Kingdom. Two years later, the Mallard throttled up to 126 mph on the same tracks, recognized internationally to this day as the world record for steam-powered trains.

Not to be lost, however, is that for one shining moment in 1891 a stretch of iron rails in Bucks County became railroading’s record-smashing speedway.

Sources include “Ninety Miles an Hour!” published in the Forest Republican newspaper of Tionesta, Pa. on Oct. 21, 1891.

Carl LaVO, whose grandfather Carl was marketing manager for the Southern Pacific Railroad in San Francisco, can be reached at [email protected]. The author will discuss the story of Castle Valley at 7 p.m. on Sept. 28 in the Syd & Sharon Martin Barn, Doylestown Historical Society, 56 S Main St,, Doylestown, Afterwards, he will sign copies of his new coffee table book“Bucks County Adventures” including 25 stories and more than 150 photographs.