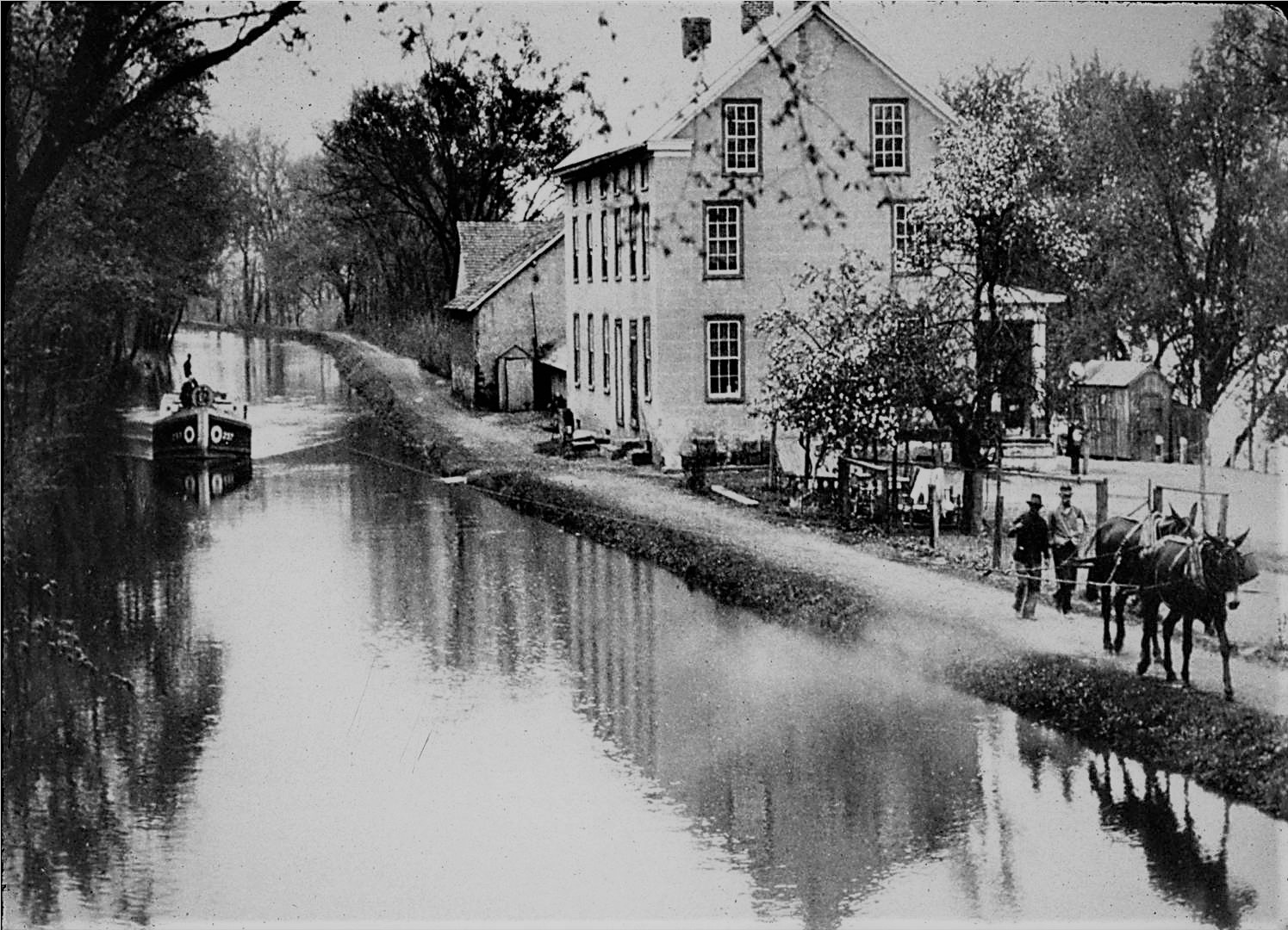

Of mule teams, lock tenders and hazards on Bucks County’s 19th century wonder.

Just about any point along the 60-mile-long Delaware Canal is a portal to the 19th century. In Upper Bucks below Riegelsville, I like to linger in the shadow of 300-foot-high cliffs cut like a knife by the Delaware River, providing just enough room for the canal to be scooped out between the river and the palisades in 1834. Downstream enchantments include a well-preserved covered bridge over the canal in picturesque Uhlerstown plus massive lock mechanisms at Lodi that once raised and lowered water levels so coal-laden boats could pass.

A stroll on the canal towpath through New Hope takes you past famous Odette’s cabaret, relocated to become a canal museum. The waterway continues through Washington Crossing Historical Park and hugs tight to the river with magnificent views in Upper Makefield. In Lower Bucks, the Italianate grandeur of the 168-foot-high Grundy clock tower looms impressively over the canal terminus in Bristol.

It’s at any one of these beautiful sites that historical dreamers like me wonder what it was like riding long, narrow scows drawn by mule teams through 23 locks from coal fields above Easton to Bristol. Many tales survive. Here’s a sampler:

‘Living like muskrats’

Generational families had jobs for life on the canal. Typically when a male reached age 14, he went to work. Each boat had a captain, mostly 15 or 16, who handled the tiller at the stern and a mule driver who could be as young as 6 like Madeline Free whose mother stitched a bloomer outfit for her to wear. “I loved them animals and they loved me and they used to cry for me and whinny every once in a while – when they knew I was getting tired and then I would crawl up on their backs and make a bed on there.”

It wasn’t unusual for families to be aboard – father, mother and siblings.

Two bunks for 4 in the crowded cabin. Others slept on a mattress on the floor or on deck.

The working day began at 4 a.m. and ended at 11 p.m. “We lived like muskrats – born and raised on the canal,” as Chester Lear put it.

The busy lock tender

State government built rent-free homes for lock tenders and their families. Flora Henry handled mules detached from the boats as they passed through her family’s assigned lock. “When a boat was about 500 yards away, the boatman would blow a conch horn so the tender would get his lock ready. If the tender had any trouble with the lock gates, he would blow a whistle of warning. This was a moment to dread, for the Captain was apt to be angry if he had to wait for his boat to be locked through.”

Return trip hazards

Most boat captains leased rather than owned a boat. In Bristol, they were given empty ones for the return trip to Easton. Differences in age, upkeep and handling were remarkable. Many boatmen shuddered at cabins overrun with bedbugs.

Managing the tiller proved more difficult that leading mules. James Lair, 14, was steering his boat while the captain was asleep one night in 1853. When the boat ran aground, the captain woke to discover Lair missing. A search the next day recovered his body just below one of the canal’s iconic hump-backed bridges. A post mortem concluded he was asleep at his post when his head struck the bridge, knocking him into the canal.

Serving the boats

Edna May Reed’s mother ran a general store on Yardley’s Edgewater Avenue. “Mom had a lot of canal trade – they would come down the canal on the boats and they would holler to her what they wanted and then she would get it ready for them and if they wanted a loaf of bread right away she would just throw it to them and they would catch it. They sold bread, soda, ice cream, canned goods, cigarettes, penny candies.”

Boatmen were known to “milk” peaches off trees along the canal and took apples and tomatoes. Farmers didn’t mind. They’d line up bottles on fence posts to challenge wayfarers to hit them with lumps of black gold. It was good sport. The growers would benefit by gathering up the anthracite to burn over the winter. Famed impressionist artist Edward W. Redfield in 1898 cut from a piece of wood the outline of a human with one arm rounded out into a circle and a sign, “Hit me!” When boatmen came in view of his home at Phillips Mill above New Hope, they joyfully fired lumps at the arm. That’s how Redfield obtained his annual winter supply.

Many “canalers” were fishermen who baited hooks with corn kernels to attract wayward chickens. As one boatman put it, “Dinner for the night on boiled canal water.”

Sources include “Pennsylvania’s Delaware Division Canal: 60 Miles of Euphoria and Frustration” by Albright G. Zimmerman published in 2000 by the National Canal Museum in Easton.