William Penn, the Lenape people and the betrayal he feared for them.

It was the summer of 1683. William Penn, 39, had just come in from the remote interior of Bucks County where he had been living with Lenape Indians to learn their language and customs. Back in Philadelphia, the Quaker founder was astounded by news he had died a Catholic. “I find some persons have had so little wit, and so much malice, as to report my death,” he scoffed. “One might had reasonably hoped that my distance, like death, would have been a protection against spite and envy,” adding, “I am still alive and no Jesuit.”

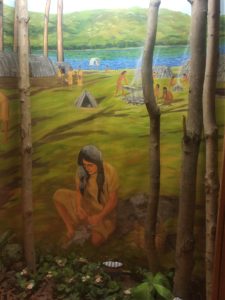

In a lengthy letter to the Free Society of Traders in London that summer, he discussed what he learned about Pennsylvania’s topography, vegetation, streams, rivers, climate, fish and game. Most of all he discussed the Indians. To them, Penn was “Onas”, meaning “writing quill”. Indeed, he kept careful notes. The Lenape, he reported, consisted of “kings, queens and great men.” They were “tall, straight, well built, and of singular proportion; they tread strong and clever, and mostly walk with a lofty chin. Of complexion black, but by design, as the gypsies in England. They grease themselves with bear’s fat clarified, and using no defense against sun and weather, their skins must be swarthy.”

Their dialect was limited but “lofty”, according to Penn. “One word serveth in the place of three, and the rest supplied by the understanding of the hearer, imperfect in their tenses, wanting in their moods. I have made it my business to understand it. I must say that I know not a language spoken in Europe that hath words of more sweetness or greatness, in accent and emphasis, than theirs.”

The care of newborns struck Penn as unusual. Mothers “wash them in water, and while very young, and in cold weather plunge them in the rivers to harden and embolden them. Having wrapped them in a clout, they lay them on a straight board a little more than the length and breadth of the child, and swaddle it fast upon the board to make it straight, wherefore all Indians have flat heads, and thus they carry them at their backs.”

Puberty also was noteworthy. “When young women are fit for marriage, they wear something upon their heads for an advertisement with their faces hardly to be seen but when they please. The age they marry, if women, is about 13 or 14; if men, 17 or 18. They are rarely older.”

Lenape society impressed the colony’s founder. “It is admirable to consider how powerful the kings are, and yet how they move by the breath of their people. I have had occasion to be in council with them upon treaties for land, and to adjust the terms of trade. Their council, the old and wise, on each hand. Behind them, or at a little distance, sit the younger fry in the same figure. Having consulted and resolved their business, the king ordered one of them to speak to me. He stood up, came to me, and in the name of the king saluted me, then took me by the hand and told me that he was ordered by his king to speak to me, and that now it was not he but the king who spoke, because what he should say was the king’s mind.”

Penn viewed Lenapi justice as oddly pecuniary. “In case of any wrong or evil fact, be it murder itself, they atone by feasts and presents of their wampum, which is proportioned to the quality of the offense or person injured, or of the sex they are of,” he noted. “It is rare that they fall out if sober; and if drunk they forgive, saying ‘It was the drink, and not the man, that abused them.’ ”

Penn and the Lenape resolved to have a European-Indian tribunal, six on each side, decide future disputes. Still, Penn was fearful of “some Christians who propagate their vices, and yield a tradition for ill and not for good things.” He hoped immigrants would adhere to the tribe’s “greater knowledge of the will of God, for it were miserable indeed for us to fall under the just censure of the poor Indian conscience.”

Returning to London, William Penn – the only single individual to found one of the 13 original colonies – died penniless of stroke in 1718 at age 73. In a touching gesture, the Lenape sent a fur cloak to his widow Hannah with a message to wear it “when you walk through the forest without your guide.” Over time, Penn’s dream for Native Americans dissolved. The Lenape would be cheated out of their lands by Penn’s sons in 1737. The tribe reluctantly left Bucks County for good in 1775, pushed irrevocably west to Canada and the territories of Wisconsin and Oklahoma.

There is much more revealed about the colony and the Lenape tribe in William Penn’s letter to the trade society as found in the “Life of William Penn” by Samuel Janney published in 1882.