The story behind the handing to two spies in Morrisville 5 years after Washington crossed the Delaware.

John Mason was doing time in a New York City jail and longed for freedom. James Ogden was a newlywed experiencing financial difficulty in New Jersey. Within 10 days, both were swinging by their necks from a tree in Morrisville. How did this happen?

The tale begins on Jan. 1, 1781 with a mutiny by 2,400 volunteers of the Pennsylvania Line fortifying northern New Jersey from possible attack by British forces occupying New York. The volunteers hadn’t received adequate pay from Congress amid deplorable conditions. What really boiled the soldiers is they enlisted three years earlier for a $20 one-time bonus. Other states like New Jersey gave each volunteer as much as $1,000. George Washington, commander-in-chief of the entire Continental Army, vainly lobbied Congress to rectify the situation.

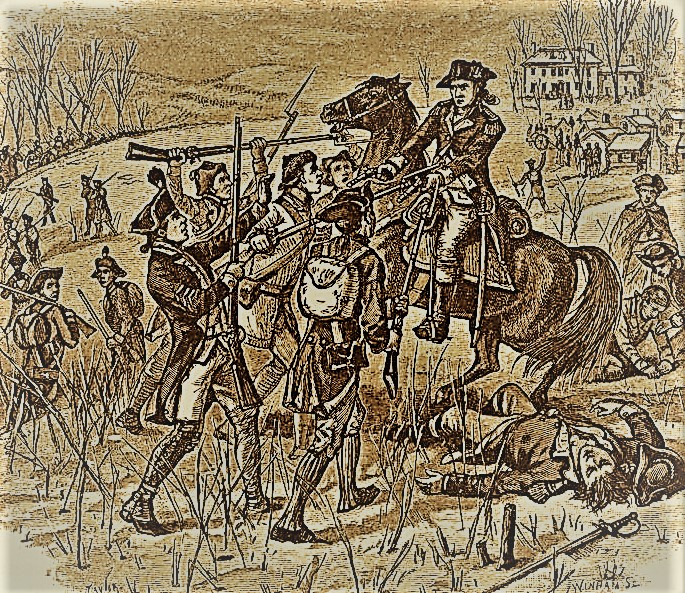

For Pennsy soldiers, enlistments were up on Dec. 31. So on New Year’s Day they wanted out. Line Gen. Anthony Wayne said they couldn’t do that. When he tried to stop them, warning shots from the mutineers resulted in one captain’s death. Afterward the army headed south to Princeton’s university where it remained, awaiting further developments. Wayne followed.

In New York, Henry Clinton, commander-in-chief of the British Army, saw opportunity. The general offered freedom and a sizeable cash bounty to prisoner John Mason of South River, N.J. if he’d deliver a sealed message to the mutineers. The letter offered a full pardon to the Pennsylvania Line, pay due them plus exemption from further military service – as long as they defected to the British.

Mason didn’t know the way to Princeton. So he sought out a hometown friend, financially-distressed newlywed James Ogden. He agreed to help for a share of Mason’s bonus. Deal. As it turned out, Gen. Clinton got a chump from prison who would be led by an innocent. If it worked out, great. If not, so be it.

On Jan. 5, Mason and Ogden arrived in Princeton where a sentry led them to John Williams, commander of the mutineers. In his office on the second floor of the college’s Nassau Hall, Mason turned over Clinton’s letter. Williams was aghast. He and his men had no intention of joining the British. He arrested both couriers and sent them to Continental Army headquarters in Trenton. There, Major Gen. Lord Sterling, the highest ranking officer, ordered their trial for espionage at Summerseat, a private mansion on the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware River in Morrisville.

It was at Summerseat five years earlier on Dec. 8, 1776 that George Washington made his headquarters after his army’s perilous escape from the pursing British across northern New Jersey. In three hours, he experienced a mini-Dunkirk by getting more than 6,000 soldiers, 40 cannon and many horses across the river to Pennsylvania via Patrick Colvin’s ferry linking Morrisville to Trenton. Washington also brought with him all boats on the Jersey side of the river, preventing the Redcoats from continuing its pursuit. The following week at Summerseat, the commander conceived his celebrated counterattack on Trenton on Christmas night that changed the course of the war.

Now, as the Revolution wound down, Mason and Ogden remained under guard in Summerseat’s basement. A tribunal presided over by Gen. Wayne convened at 8 p.m. on Jan. 10 and quickly ruled the two men “came clearly within the description of spies and that according to the rules and customs of nations at war they ought to be hung by the neck until they are dead.” Sterling confirmed the verdict and set the men’s execution for 9 a.m. the next day.

At 4 a.m., guards woke the two and served them breakfast. Meanwhile, the Philadelphia Light Horse brigade in Trenton arrived at Summerseat. Guards brought the prisoners outside, their hands tightly bound. An officer announced death by hanging. The brigade took charge of the shaken captives and marched them a half-mile down the hill from Summerseat to the Colvin ferry landing. The location is where today’s stone bridge carries Amtrak’s high speed rail line over the river on South Delmorr Avenue just below Route 1. Orders were passed to Colvin’s slave to hang the prisoners from a tree at the landing. By noon on Jan. 11, 1781 the sentences were carried out. The men were left dangling as the brigade departed for Philadelphia. Five days later ferry passengers reported the bodies still swaying in the wind, an overt warning to Gen. Clinton and the British.

The executions brought the mutiny in Princeton to a quick negotiated end though the war would go on for another two years.

Sources include “Spies in the Continental Capital: Espionage Across Pennsylvania During the American Revolution” by John A. Nagy published by Westholme Yardley, 2011; “The Writings of George Washington”, Vol. 21 published by the U.S. Government Printing Office, 1976; and “Ferries spanned the Delaware before Advent of Bridges” by Samuel C. Eastburn published in the Delaware Valley Advance, 1929.