It was supposed to be Bucks County’s grand central park – in Wrightstown.

William Penn left many footprints that have survived for more than 300 years. Like his rebuilt manor home in Falls overlooking the Delaware River. Like the state named for him. And, of course, the first three counties he founded – Philadelphia, Chester and Bucks. In his drive to create a commonwealth of harmonious human relations amid the natural environment, he envisioned a future for Bucks that would include a grand central park. He carefully chose the site and mapped out its boundaries – a one–square-mile configuration of 640 acres. That compares to 843 acres of today’s Central Park in New York City.

The Bucks park was to be patterned after those in Penn’s native England. It would be a landscaped central place in Buckingham Township where townspeople, farmers and merchants could socialize and do business. To Penn it would be reminiscent of English squares surrounded by homes with gardens extending into the grassy confines and open to the public.

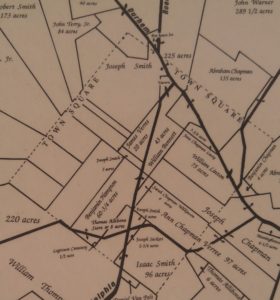

Billy Penn conceived two squares, the other in Newtown Township. But landowners there purchased tracts that extended well into intended open space, eventually whittled down to a meager 40 acres. Penn’s park, on the other hand, was set aside entirely as preserved acreage. After an inspection in 1687, Penn’s close friend Phineas Pemberton described it as ideal, flat with fertile soil and heavy with timber. Plus there were no streams running across it that might cause erosion.

John Chapman was the first European immigrant to buy property adjacent to the parkland. He, his wife and children sailed from Yorkshire, England, in 1684 to take possession of 500 acres. Life was rough. On arrival, the family moved into a cave in a ravine off today’s Mud Road where Mrs. Chapman gave birth to twins. William Smith and his Yorkshire family arrived later that year and built a log house. Before long, a Quaker community of about a dozen families had purchased farmland all around Penn’s park. Squatters also took up residence inside the commons where they built make-shift log cabins known as “Logtown”.

As a farming community, residents were hardy and self-sufficient. Surplus crops of butter, poultry, fresh meats and grain were shipped to market in Bristol in sacks atop a string of horses led by women. They followed an Indian path that became Durham Road (Route 413) once horse-drawn carts appeared on the scene. Henceforth, women yielded the marketing to men.

A land survey of Buckingham in 1703 partitioned off and formalized “Wrightstown Township” where Penn’s park was located. From London, he named it after his good pal Thomas Wright of Burlington, N.J. Settlers nearly popped their coonskin hats when they heard the news. They considered Wright an interloper. Settlers much preferred “Centretown” for the area’s geographic position in the county.

After the founder’s passing in 1718, there still had been no moves to enhance the park. Landowners finally shouted “Get real!” and persuaded local government to sell the commons to them in proportions equal to their abutting lands. No more park.

Wrightstown would go on to some noteworthy events in coming years. A chestnut tree in front of the local Quaker meeting house on Durham Road became the starting point of the infamous “Walking Purchase” of 1737. It was a race by three Anglo runners hired by Penn’s children to swindle Native Americans out of acreage that enlarged Bucks County all the way to the Pocono Mountains. Also, a horseback rider blitzed through town at Christmas 1776, singing and shouting, “The Hessians are taken! The Hessians are taken!” after George Washington’s dramatic victory in Trenton.

Today the original boundaries of Penn’s park are hard to decipher. I had a 1991 map by the Wrightstown Township Historical Commission showing acreage on both sides of Durham Road. I suspected Wrightstown’s expansive Middletown Grange fairgrounds might have been part of the park. Nope. It only borders it. I did find William Smith’s 1684 log home however. Some consider it the oldest in Bucks. Beautifully maintained, it’s been expanded into a much larger private home not far from where original settler Chapman and his family once lived off Mud Road. It’s interesting to contemplate who descended from those cave dwellers: Henry Chapman Mercer, the genius behind Doylestown’s Mercer Museum, Fonthill Castle and Moravian Tile Works.

By the 19th century, Victorian homes, a store, tavern plus blacksmith, wheelwright, carpenter shops and a slaughterhouse gave shape to “Pennsville” on the upper border of the original park on Route 232 (Second Street Pike). A mile down the road toward Richboro is the former village school, an iconic, one-of-a-kind octagonal, stone building built in 1801 that’s now a museum.

In 1862 Pennsville got a permanent name change when a post office opened. For people like me that name – “Penn’s Park” – became the bait to rediscover the park that never was.

Sources for this column include “Wrightstown Township: A Tricentennial History” by Jeffrey L. Marshall and Bertha S. Davis published in 1992 and a memoir by Annie C. Scarborough published in 1883 in “A Collection of Papers Read Before the Bucks County Historical Society: Volume 1″ distributed by the society in 1908.